A Significant Connection

Recently a joint meeting of the Diocesan Council and the Dunedin Diocesan Trust Board asked the Bishop to relay congratulations from the diocese to Rev'd Dr Paul Oestreicher on reception of his OBE.

The resolution (from a motion moved by Dr Tony Fitchett) read: "that a message of support be sent to Rev Dr Paul Oestreicher for the OBE awarded to him in the UK Queen’s Birthday Honours in light of his strong connections with the Diocese of Dunedin."

Bishop Steve sent a letter of congratulation and received a lovely reply, excerpts of which follow:

My warmest thanks for your kind and perceptive message. Coming from the Bishop of my home Diocese, that had its own very special significance. Bishop Fitchett confirmed me, Charles Harrison at All Saints was my mentor and inspiration until his death. When, working for the BBC, I was offered the post of Head of Religious Broadcasting by Radio New Zealand, a job I had to decline, Father Charles took the post. Given the secularisation of society, the job no longer exists, a sign of the times. Bishop Alan Johnstone, in England for Lambeth 1968, conducted my wedding at Lincoln Theological College. I was still an Otago ordinand. Many years later my Otago Hon.DD remains greatly treasured. Back in 1939, Archdeacon Whitehead, Warden of Selwyn College, had sponsored my German/Jewish refugee family.

That is not the most important part of my Dunedin Anglican history which began on my 19th birthday, Michaelmas 1950. Then, a young Quaker, my girlfriend took me to my first ever Anglican Communion Service to her parish church, St. Michael and all Angels, Anderson's Bay. I can't escape the Archangel.

That Eucharist was like a second conversion. I never looked back. My hope is that this year, from age 19 to 91, I may, God willing, be back at that church at Communion on the patronal festival with the same girl, Louise Petherbridge, 91 like me. Not until aged 53 did I also return to my Quaker roots, encouraged by Archbishop Michael Ramsey....

...I'm learning to live with the OBE (Order of the Benign Elephant - forget the Empire) but thanks for the congratulations.

Paul also sent more detailed information about his life, which we know many people will be interested in reading:

Paul writing to his friends near and far from Wellington, Aotearoa.

This seems a good moment to gratefully share with you some of the milestones on my pilgrimage, as my OBE citation says, for ‘peace, human rights, reconciliation, and the Church’. These are the things that will continue to motivate me. A state award – I had already received a German one – is only acceptable as an affirmation of these values and of all those who have worked with me to embody them. PARAMOUNT among them is the priest, prophet and my role model BRUCE KENT who has left us, but leaves his indefatigable spirit, his joyful warmth, his dedication to peace, his passion for justice and his humble determination to leave the world a better place. In Yiddish, he was a Mensch – a true human being. It is to BRUCE, my friend, that I dedicate the eight narratives that follow. Each one may just possibly illustrate in some way what he and I have stood for, with no award in mind. Our sole reward is in the love of humanity that each of them expresses.

1. Reconciliation

Let me begin with reconciliation. It started early. Trying to make peace between my often warring parents helped to shape my childhood. What’s more, I was born on Michaelmas 1931, the year when Hitler came to power in my birth state of Thuringia. The Archangel Michael, who has never left me, had expelled injustice from heaven (Rev.12.7) and goes on fighting it on earth with the weapons of the Spirit. He equips me for the struggle. Speaking of the Spirit, at this season of Pentecost, we are all set free to benefit from the ‘glorious liberty of the children of God’. Who are these children? My elder daughter answered that question at primary school. Asked to what race her black brother belonged, she replied: ‘the human race’.

On the Dutch luxury liner that took my refugee family from Amsterdam halfway to New Zealand, I first encountered the injustices of colonialism. As a first-class passenger, my Javanese servant Suliman was at my beck-and-call and soon became my friend. I, nosey boy, stumbled on the fact that the native workers, dressed at work in smart uniforms, slept, half naked, under the engine room, on mats at the very bottom of the ship. I was the privileged boy at the top, and they, far down below. At seven years old, I felt guilty, deeply shaken. This ship, as I now know, was a microcosm of our unequal world. Unequal and unacceptable.

[Just to explain, how come that a refugee family was travelling in such state? Thanks, paradoxically, to Nazi laws. They wanted to get rid of Jews. My father’s bank account had been confiscated. But to get to our foreign destination, the State Travel Bureau was permitted to draw on my father’s blocked account. So, logically, my father figured that the more expensive the journey, the less money was left to the Nazi state].

2. London in the 1960s

Fast forward to London in 1963. My first job as a priest on leaving my teaching parish, was as a radio features producer in the Religious Broadcasting Department of the BBC. Canon Roy McKay, my boss, encouraged me to be adventurous. I was the editor of a 40-minute feature every Sunday evening. A year into this series, abortion, still completely illegal, was becoming a contested moral and political issue. The BBC was reluctant to touch it. I felt strongly that women should be heard. But how? Attacking abortion or defending it or simply neutrally debating it on air? The social climate was not ready. Instead, I got permission for something bolder and much more deeply human.

I invited Lesie Smith, a well-known and sensitive interviewer, to enable a number of women who had had illegal abortions, each to tell her story anonymously - with no editorial comment. They had broken the law and were prepared to tell it just as it was. No two stories were alike. Some were shocking. All were moving, some to tears.

Here was human reality, without doctrinal presuppositions. Having listened, it would be easier to debate the issues sanely. That happened. Abortion law reform did follow a few years later. With this feature Never to be Born, the BBC won an American radio award. If only Americans today might listen to such a cross-section of women - and truly hear them.

3. The Berlin Wall

Still in 1963, two years after the Berlin Wall went up. Heinz Brandt had been a prominent East German trade union leader with a long Communist history. He had suffered in Hitler’s prisons. However, disillusioned by the East German regime, he defected to the West. The Stasi state security kidnapped him as a traitor and sentenced him to 13 years in prison. Amnesty International adopted him as a prisoner of conscience and sent Canon John Collins and me on a mission to plead for his release. We were received by Walter Ulbricht, East German Head of State, and officially described, at his insistence, as a ‘peace delegation’.

It turned into three hours of listening to Ulbricht, defending the Berlin Wall and his ‘peace policies’. His friendliness turned to bitterness when we raised the issue of his most hated prisoner. We were well prepared and did not give him an easy time. Reluctantly, he accepted the dossier we put before him. After many cups of not the best coffee, he turned to us: ‘Gentlemen, I cannot understand you as Christians pleading for this miserable Communist turn-coat’. ‘Herr Ulbricht, I said, ‘he is a human being’. End of encounter.

Brandt’s sentence was reduced from thirteen years to three. On release, he was made Amnesty’s prisoner of the year and lit the Amnesty candle in St Paul’s Cathedral. He later became a leading member of the West German Greens.

4. London 1969 - 1981

Move on to the Church of the Ascension, Blackheath in South-East London, my first and only parish from 1969-1981. Deaconess Elsie Baker was its pastoral heart. She eventually became one of the first women ordained to the priesthood in the Church of England. The Quaye family were parishioners, though not churchgoers. Mother was white. Father was a railway worker from Ghana. They had two black daughters. They fell foul, for no good reason, of the Greenwich Police. A detective officer so harassed the family, that one by one they spent time in the cells. So blatant was the racism, that our curate, Bob Whyte, who with his wife had formed the Blackheath Commune, took the matter to law. The family were exonerated, the detective disciplined. Father and Mother eventually returned to Ghana.

The story was published in the Sunday Times. Thereupon the National Front, the far Right in the 1970s, staged a Sunday morning demonstration at our Church. Some held placards demanding the dismissal of the curate, others came into the church to heckle at the eucharist. I halted the worship and invited the hecklers to come forward to state their case. They were clearly not up to that. So, I invited them to come to meet parishioners on the following Wednesday. Some of them came. They had hoped we would call the police and create an incident. That, for the opposite reason, was our Bishop’s view too. Not ours. We were a Church for all people, friends and foes, Black and Right. It was in our parish on Blackheath that in 1381 John Ball, Wat Tyler’s priest, had preached to the peasants before they marched on Westminster, that ‘under God, all shall be one’. Just as with Jesus, they killed him.

5. Back to Germany

Five years later, move on with me now to Stuttgart in Germany. Its top security prison held the leaders of the Red Army Faction, also known as the Baader-Meinhof Gang. They had killed many in their hopeless dream of smashing capitalist society. In this and other prisons they had gone on hunger strike in their fight, as they claimed, for better prison conditions. They had fasted long enough for one of them to die. The Minister of Justice and the prisoners’ families, most of whom did not share their convictions, appealed to me, as an outsider who spoke German, to persuade them to end the fast. That would save not only their lives. In retaliation for the one who had died, a judge had already been murdered.

So, I set out on this, as it seemed to me, hopeless task, in four prisons. There is no way I could refuse, so may God help me. There was an unforgettable moment in Hamburg Prison. The room was small. Two of the prisoners sat at a table facing me. They, like all of the gang, showed every sign of rejecting me as just one more symbol of bourgeois society. A prison chaplain had hung a text by Dietrich Bonhoeffer on the wall behind them: ‘You will never help anyone whom you despise’. I knew I had to make that text my own.

I did manage to treat each one of them as a person to be respected and, Jesus would have said, loved. I was a go-between them and the Attorney General who determined their prison conditions. He too was not easy to like - and love. Small steps were taken. The moment came when I could do no more. Th prisoners broke off the strike. It was their decision, not mine.

They soon appeared in court, a few at a time. Their leaders carried on the fight by killing themselves with weapons smuggled into their cells. Their comrades outside claimed that it was murder and went on to kill Attorney-General Buback. Only the idealist Ulrike Meinhof gave up the struggle, the ultimate despairing nihilist - and hanged herself.

Was it a journey to hell and back? I think not. It was an experience of the human condition, never beyond redemption, crying out for mercy.

6. Onto the USSR

Next stop, Saint Petersburg in 1978, then still called Leningrad and Putin’s hometown. Dramatically, my in many respects Russian counterpart, Metropolitan Nikodim, Foreign Relations Head of the Russian Orthodox Church, died of a heart-attack in the presence of Pope John Paul l, who himself died a few days later. Rumour, almost certainly false, claims that both, separately, were murdered.

Cardinal Suenens, the Vatican’s chief ecumenist, brought the body of Nikodim, whom I had known well, back from Rome to the city of which he was Archbishop. An impressive funeral was held in Leningrad Cathedral. Seven thousand people came. Bishop Runcie, later himself Archbishop, was delegated to represent the Archbishop of Canterbury. Robert Runcie asked me to accompany him. I was refused a visa. Runcie told the Soviet Ambassador that he would not go without me. So I got the visa.

I will not describe the seven-hour long funeral.

Back at the airport, Bishop Runcie left for London before my flight via Berlin. My designated translator, Ivan Potatov, for lack of professional interpreters, had quickly become a friend. He normally translated English theological books for the Orthodox Seminary. We had a two- hour wait before my flight. Would I buy him a meal at the international restaurant, better and more expensive than the Russian one? And quieter. In a far corner, he asked me why his bosses (the KGB, who else?) had told him I was a dangerous person. That’s simple, I said. I am the chairman of Amnesty International in Britain.

Ivan looked at me in total amazement. Could this be true? ‘But for Amnesty International, I would still be in prison. After a student protest at the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, a group of us were sentenced to twelve years. Amnesty’s appeal meant that I only served for four. Now I am normally only allowed to leave my village once a month to deliver my translations. And today I am meeting Amnesty, in you. It is a miracle!’

It was. From then on, I sent Ivan Penguin paperback novels. No politics. He has since died.

7. Out of Africa

And now to Ulundi, to the seat of Zulu Chief Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi. South African Apartheid was close to collapse. Freedom was in the air, yet a civil war still raged. Buthelezi’s Inkatha Freedom Party was at war with the African National Congress. Could the Zulu Chief be persuaded to end the conflict and to join Mandela and the rest of the nation in its first free election?

Desmond Tutu invited me, his colleague Bishop Michael Nuttall hosted me, to join with others to persuade Chief Buthelezi to change his mind. I had accommodated the Chief on a visit to London. A devout Anglican, he had stayed at the diocesan retreat house of which I was chaplain. We trusted each other. Twice I flew to Ulundi in the chief’s own plane. Long conversations ensued. Behind the scenes, opposite pressures were being brought to bear. The chief listened patiently. Finally, I believe it was the Foreign Minister of Nigeria who tipped the balance. The conflict ended. Buthelezi joined the first cabinet of a freely elected South African Government.

8. The Cold War

The struggle against nuclear weapons reached its zenith in 1983 when both sides in the Cold War began to station intermediate-range nuclear weapons in eastern and western Europe. The peace movement in West Germany saw its largest ever demonstration. Tensions on both sides of the Berlin Wall had never been greater. Western peace campaigners were not welcome in East Berlin. The nuclear threat seemed all too real.

In December, I received a phone call. ‘Do you know Barbara Einhorn?’ ‘No, but I’ve always wanted to meet her.’ ‘We think you might be able to help. She went to East Berlin on behalf of END, (European Nuclear Disarmament) to meet the East German campaigning group “Women for Peace”. She has not returned as expected. We fear she may have been arrested.’

Given my contacts, I quickly found out that it was indeed so. She was in the Stasi Prison in East Berlin, along with two of the East German women whose existence she had hoped to make better known in the West. That was held by the Stasi to be ‘treasonable’.

Meanwhile, a campaign rapidly got under way around the world to set this New Zealand academic free. Contrary to international law, her arrest had not been admitted by the East Germans. The NZ and UK Governments protested. The press had the story. After five days and nights of interrogation, her captors decided she was more trouble in than out of prison, dropped the charges and expelled her from the country.

Barbara returned to her family in good time for Christmas. In January 1984 we met for the first time at a meeting of END members to discuss what could be done to help the two East German women who had not yet been freed. They were held for six weeks.

Reflecting on these Eight Encounters

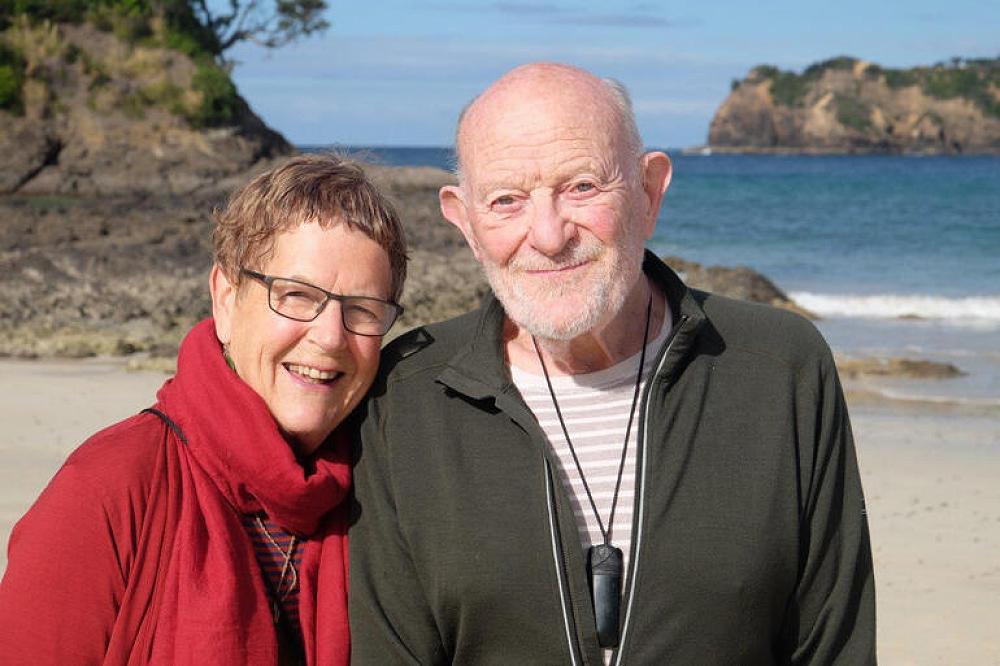

DEAR FRIENDS, may these eight encounters, in the course of my privileged life, suffice to illustrate my work for ‘peace. human rights and reconciliation’. The fourth good cause flagged up in my OBE citation was the Church. But for the Church of England which sustained this troublesome gadfly throughout his working life, but for the Society of Friends (the Quakers), but for the British Council of Churches, and finally, Coventry Cathedral, none of this would have been possible. The Archangel Michael and the Holy Spirit have never given up on me. Nor did my forbearing wife Lore, who brought up four children in the all too frequent absence of their father. She died too soon in the year 2000. Barbara and I married in 2002, in Berlin, from where our parents had fled in 1939. We have gone on campaigning together. We could not be happier. We are amazingly fortunate.

Barbara joins me in sending you – in the beautiful Māori language – much love: AROHANUI

PAUL