Support and inclusion lacking for first-time fathers

Suzanne Hodgson - Unitec, Te Pūkenga: New research shows a need for an improved awareness of the experiences of first-time fathers to inform policy and practice – and to improve support and outcomes for these men and their families.

Unitec Nursing Lecturer, Dr Suzanne Hodgson, first became interested in men’s transitions to fatherhood when she worked as a Health Visitor in the UK, supporting families with children from birth to five years old.

Using the constructivist grounded theory method, Hodgson conducted semi-structured interviews with 12 first-time fathers in heterosexual, cisgendered relationships in the North of England about their experiences of and perspectives on becoming fathers. At the time of the interviews, their children were aged from three months to 18 months old.

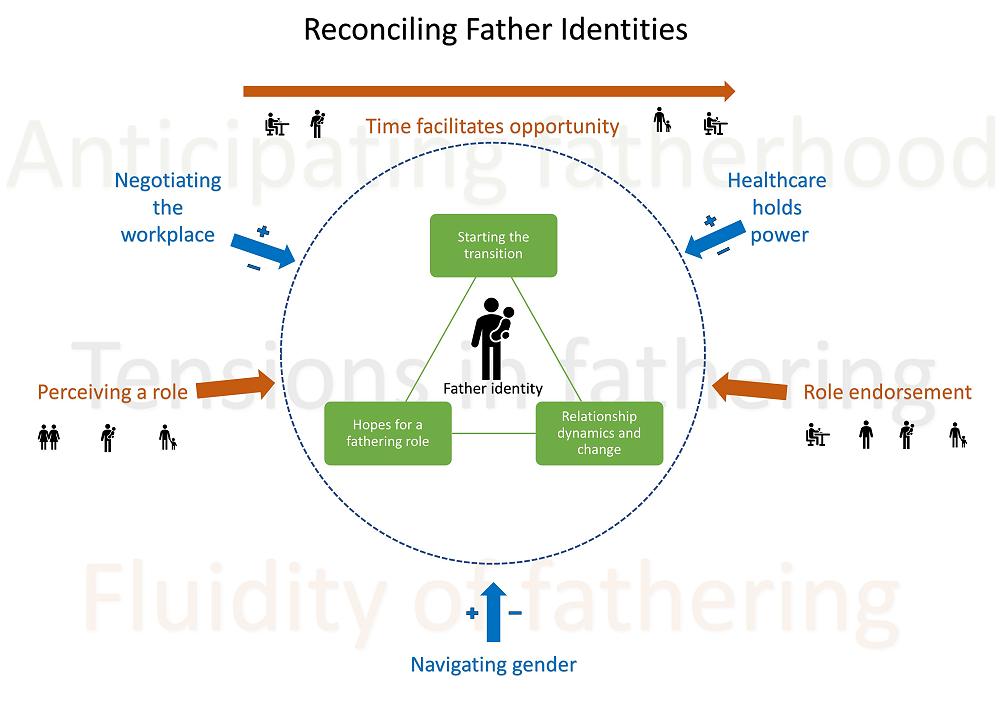

“I analysed the data and constructed the core category of reconciling father identities with three theoretical categories: anticipating fatherhood, tensions in fathering and the fluidity of fathering. The study revealed the many influences on men as they become dads for the first time. Men had strong ambitions related to who they were going to be and what they were going to do as dads, but this was often inhibited by the individual circumstances they found themselves in. They therefore had to settle for a different type of fathering reality from the one they had perhaps expected.”

She found all participants had strongly aspired to be involved fathers and took steps to prepare for their new roles prior to the birth of their babies. However, she says they faced various tensions in the workplace, in health care settings and in expectations influenced by social and structural gender norms.

“The father roles that they were ascribed by others frequently did not fit with their aspirations during pregnancy and the early months as fathers,” she says.

While all of the participants felt appreciative of the health care their babies and partners had received, they themselves described feeling excluded or out of place.

“They talked about not being in the loop as far as conversations were concerned, and of a sense of being side-lined,” says Hodgson. “Some had experienced emergency situations with their partners or babies during pregnancy or birth, and said they were not communicated with during the event. They had no idea what was happening and were fearing the worst because they were not informed or reassured at any point.”

Some participants had previously experienced pregnancy loss, which heightened their level of fear throughout pregnancy and birth – and also had an impact on their behaviour.

“One dad had been really engaged in the first pregnancy which resulted in loss, and had then completely detached himself from the second pregnancy as a protective mechanism,” she says. “Another had been a little bit reserved in the early stages of the first pregnancy, but after it resulted in a loss, he was very engaged with the second pregnancy – to the point where he was intensely monitoring his partner and wanting to know everything that was happening in the pregnancy.”

She said there was no support offered to these men, or recognition of the impacts these losses had on them.

“Individuals respond differently to pregnancy loss, but providing acknowledgement and support for fathers who have experienced pregnancy loss will benefit both partners navigating a subsequent pregnancy.”

The participants spoke about antenatal classes – while some found them helpful, others felt they weren’t useful for them at all.

“In terms of antenatal resources and support, they found it very difficult to access any information especially for fathers,” says Hodgson. “They really wanted information that would help them prepare for what was to come, but they felt it was significantly lacking.”

Following birth, the participants described feeling immense gratitude and relief that their babies and partners were safe and well. They also commented that these feelings overpowered any negative experiences up to that point.

The majority of the participants had a maximum of two weeks’ paternity leave.

“They said it was challenging to return to work after their paternity leave – they started to feel that sense of exclusion again,” Hodgson says. “They missed out on seeing some of their babies’ milestones and weren’t there to interact with Health Visitors. There wasn’t any opportunity for them to discuss their roles or experiences as parents, or to consider their own mental wellbeing.”

Participants spoke about their sadness and disappointment at the lack of time they got to spend with their babies.

“Many were getting up to go to work before their babies were awake, and only had an hour with their children at the end of the day before bedtime,” she says. “They found it difficult to reconcile their identities as fathers with the realities of their daily lives – they had expectations of being involved fathers, but had to prioritise their workplace requirements which limited their time with their babies.”

She says broader consideration of the needs of fathers in both health care settings and in the workplace would help support the development of positive father identities.

“I’d like to see greater inclusion, workplace flexibility and an acknowledgement from society that fathers have an important role to play. This has the potential to significantly benefit the wellbeing of fathers, their partners and their infants.”

Hodgson is keen to continue to explore transitions to fatherhood in a New Zealand context.

“There are strong arguments for exploring potential connections between transitions to fatherhood, relationship breakdown and suicide rates for men in New Zealand,” she says. “I am also interested in exploring fatherhood in groups that are underrepresented in the literature, including Māori men, men of Asian and Pacific descent, and men who are separated from their children due to relationship breakdown or incarceration.”

Dr Suzy Hodgson is a lecturer in nursing at Unitec, Te Pūkenga. She has a background in both children’s nursing and public health nursing in the UK and in New Zealand which is where her research interests in fatherhood began. Over the past nine years, she has worked in academia and completed her PhD in transitions to fatherhood in October 2021. Suzy has developed a strong network of fellow researchers, practice partners and experts by experience, and has disseminated her findings throughout her PhD at conferences, practitioner workshops and via peer reviewed publications. Her current and future research has a focus on improving paternal perinatal wellbeing with an emphasis on applying research to practice in the New Zealand context.

Contact Suzy Hodgson

Visit Unitec, Te Pūkenga