Holistic Discipleship: Embracing the Mission of God to All of Creation Through a ‘Green’ Reading of Revelation

This article is an amended version of a paper given originally at the 2017 School of Theology held at Bishopdale College in Nelson. It also draws on my Master's Thesis: Alas for the Earth: An Ecocritical Reading of Revelation (2016) which contains a more detailed account of some of the issues raised here, particularly in the exegesis of selected texts in Revelation.

“Alas for the Earth!”[1] We might well echo this exclamation from Revelation 12:12 as we look at current challenges to the flourishing, and even the sustainability, of life on our planet. Human impact on the environment is now global in scope and has led some geologists to declare that we have entered a new geological era – the Anthropocene.[2] The effects of this are well known: global warming, rising sea levels, the pollution and destruction of habitats, and the endangerment and loss of plant and animal species, as well as the disruption to traditional ways of life.[3] Often it is the poorest communities that are disproportionately affected as they are least able to cope with the aftermath of sudden disasters or to adjust to the degradation or loss of a traditional resource base. Environmental issues are frequently also social justice issues and can become political issues.[4] Increasingly, churches are called on to make a Christian response to the problems and opportunities presented by large-scale movements of people at local, national, and international levels.

However, I want to focus on our response to current environmental issues, particularly in the light of the accusation that it is the Christian worldview that is largely to blame. David Attenborough is echoing the earlier criticisms by Lynn White Jr.[5] when he says, “Judeo-Christians ... believed that nature was hostile. You can see in the old testament [sic] that the natural world was there to exploit – it was there for their benefit. That has cast a long shadow.”[6]

By contrast, traditional societies are often seen as being in closer contact with, and having a greater care for, their environment than the contemporary world. For example, the Māori concept of kaitiakitanga,[7] and traditional practices such as rāhui[8] served to protect land and water resources. Nevertheless, my conviction is that there are insights within the biblical tradition that enable us to move beyond pragmatic self-interest as an encouragement to adopt ecologically responsible lifestyles. The Bible, as God’s Word to us, reveals the character and concerns of God including his concerns for the Earth he has created. If we read Revelation, say, with a particular focus on ecological issues, these concerns become apparent. They should then mould and shape our lives as we participate in the missio Dei to the totality of God’s creation. This is what I have called holistic discipleship.

Holistic Discipleship

The Anglican Communion has identified Five Marks of Mission which express their commitment to, and understanding of, God’s holistic and integral mission. The fifth of these is: “To strive to safeguard the integrity of creation, and sustain and renew the life of the earth.”[9] Similarly, the Catholic tradition has embraced the concept of an “ecological conversion.”[10] Pope Francis writes, “So what they all [Christians] need is an ‘ecological conversion,’ whereby the effects of their encounter with Jesus Christ become evident in their relationship with the world around them.”[11]

One way that we, as Christians, can open up ourselves to this experience is to reflect on the theological insights that can be derived from an eco-critical or ‘green’ reading of Revelation. This encourages us to move beyond traditional discipleship thinking to the wider perspective of holistic discipleship which recognises that creation care is an integral part of the mission of God to all of creation, a mission that we are called to be part of. It also informs and expands on the widely embraced stewardship model of creation care.[12]

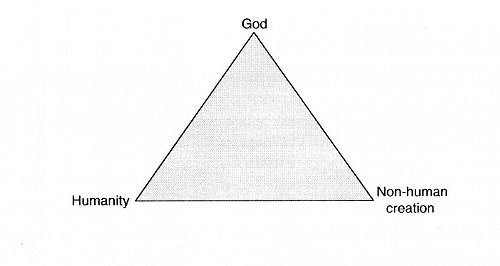

Christians commonly describe discipleship in terms of our up, in, and out relationships: God, church family, and the world. However, ‘the world’ is often interpreted narrowly as referencing only other people rather than the totality of creation. As embodied beings living in a material universe we are challenged to live in a responsible relationship with both the animate and inanimate world around us. This is often portrayed as a triangular relationship similar to that found in image one below,[13] although Bauckham proposes a quadrilateral model of relationships to differentiate between the animate and inanimate creation.[14]

Our relationship with God retains its prime position but God is in two-way relationships not only with humanity but also with the non-human creation. Two-way interactions also take place along the baseline of the triangle between humankind and the non-human creation, reminding us that we are part of the community of creation.[15] This article does not attempt to draw out what that might look like in our daily lives. In a recent issue of Stimulus, Lynne Baab identified the spiritual disciplines that can sustain us on the way. Similarly, Chris Naylor and Kristel Van Houte described their participation in A Rocha projects in Lebanon and New Zealand respectively.[16] Instead, I focus on the outworking of this triangular web of relationships as portrayed in Revelation and how this portrayal informs our understanding of the mission of God.

Why Revelation?

Revelation may seem an odd choice – why not Genesis 1 and 2, one of the Psalms, or Romans 8?[17] Revelation opens up many interesting insights, for it has been comparatively neglected as an area of study with regard to environmental issues. Perhaps this is because of the violence done to the earth in Revelation 6 – 20 and, particularly, the earth’s “passing away” (Rev 21:1). These concerns have not only seen Revelation labelled as an “inconvenient text” by some environmentalists[18] but have also led some Christian constituencies to neglect or even reject environmental concerns altogether.[19] Some ask, “Why bother if it’s all going to burn up?” – although the conflagration of the cosmos is nowhere mentioned in Revelation. [20] Nevertheless, I think Revelation contains valuable insights that I hope will encourage us all to become more ecologically responsible.

Taking Revelation as a late first century text, we find a letter written by John to Christian believers in Asia Minor encouraging them to persevere as they face daily pressure to conform to society’s values and to the demands of the Roman Empire, as well as the threat of possible persecution. John’s visions give an insight into present realities as well as the future hope of a renewed heaven and earth.

I use an eco-critical approach which explores how nature and humanity’s relationship to non-human entities are portrayed in the text.[21] I also look at God’s relationship with his creation. Reading the text in this way allows themes with ecological significance to come to the fore whilst recognising that these were not the focus of John’s concerns at the time. It enables us to look at what Revelation has to say about God in relation to his creation; the non-human creation; human accountability towards the human and non-human creation – especially in the light of John’s critique of Babylon; and God’s final purposes for his creation.

God in Revelation

Revelation is firmly theocentric, a useful counterbalance to our often anthropocentric perspective. As disciples, our primary relationship is Godward. In Revelation, John is calling his readers to recognise the Lordship of Christ, not the emperor, and to persevere in their allegiance to him. God is introduced as the Sovereign, Lord God Almighty. This is voiced in God’s self-designation (Rev 1:8) and then in the worship of heaven dispersed throughout the book.[22] God is also identified as the ‘One on the throne,’ depicted in splendour in Revelation 4, at the centre of all heavenly worship and the worship of the whole cosmos in Rev 4:6b–11; 5:9–14. All subsequent activity, including the seal, trumpet, and bowl judgments, emanate from the throne room.[23]

God is also the Alpha and Omega, the Beginning and the End (1:8; 21:6), epithets identifying him as the Lord of history, the one directing all events on earth. These titles also apply to Christ (1:17; 22:13) whom John has seen in his heavenly splendour as the risen and ascended Lord (1:12–20).

These appellations and visions not only function as part of John’s polemic against Babylon/Rome, or indeed any hegemony that seeks to exercise global power or influence, they depict a cosmic reality. Apprehending God as Alpha and Omega allows us to move beyond the timeframe of human history – to look back to the origins of the non-human created universe and its evolutionary history, and also to look forward to its eschatological fulfilment or telos. This awareness of God’s relationship to the totality of his creation can provide a significant counter to the anthropocentric tradition of biblical interpretation noted by Lynn White Jr. and subsequent critics. The non-human creation can be seen to have a functioning relationship with its Creator independent of and prior to the appearance of human beings. Contra the view that ‘nature’ is solely a human construct, the non-human creation has an integrity in its relation to God that is independent of its relation to humanity,[24] an idea that I will explore further.

God is also designated as Creator. God as Creator has a threefold emphasis in the worship of Rev 4:11 and it is further intimated in 5:13, 10:6, and in 14:4 before God’s renewal of creation in 21:1, 5. The notion of God as Creator has been largely neglected by many commentators on the book of Revelation,[25] but when allied with God’s self-revelation as “Alpha and Omega,” and also as “the One who is and who was and who is coming,” God as Creator is shown to be not only foundational to the theology of Revelation but also integral to the trajectory of its metanarrative. We see the mission of God unfold in Revelation for God has created all things (4:11), is the One present with his creation in its current suffering (1:4; 12:12), and all creation, including the non-human creation, will find its fulfilment in the future coming of God and his renewal of all things (21:1–6).

The role of Christ in this redemption of creation is significant. In Revelation 3:14, Christ is described as, the archē, the “ruler”[26] or the “origin/beginning”[27] of God’s creation.[28] It is possible that John has in mind not only Christ’s sovereignty over the original creation but also that Christ’s resurrection makes him both the inaugurator and ruler over the new creation.[29] Denis Edwards argues that the transformation of Christ’s resurrected body points to the promise of the transformation of all things in God,[30] and Thomas Torrance similarly asserts, “God has decisively bound himself to the created universe and the created universe to himself, with such an unbreakable bond that the Christian hope of redemption and recreation extends not just to human beings but to the universe as a whole.”[31] Through Christ’s incarnation and resurrection, humanity along with the whole of creation are bound together in the redeemed community of creation and, “reality is ontologically relational.”[32] This understanding of the role of the resurrected Christ not only provides additional insight into the relationship of the triune God with his creation but also underscores the profound nature of the relationship between humanity and the non-human creation, what Niels Gregersen has termed “deep incarnation.”[33]

God can also be described as the faithful Creator, the covenant partner of creation, symbolised by the rainbow around the throne (4:3). Even the scenes of judgment scattered throughout Revelation and culminating in the final judgment in Rev 20 demonstrate God’s continuing commitment to his creation as he destroys those who destroy the earth (Rev 11:18). The judgment in Rev 20:11 – 21:1 portrays the actions of a faithful Creator as he acts justly to renew a creation that has been damaged by the “destroyers of the earth.” I would also argue that the fleeing universe of Rev 20:11 symbolises not so much its destruction but rather the removal of the old order before the new order of creation, free from the confines of transience and mortality, can come into being (Rev 21:1).[34]

God’s continuing commitment to his creation as portrayed in Revelation can offer a resource for further theological reflection on our own commitment to creation even as we acknowledge its “passing away” (21:1).

Non-human Creation

How do you see the non-human creation? Do you see it as something in its own right? Alternatively, do you tend to think of it in relation to yourself as a place to go to enjoy yourself? Or, a resource that provides us with food, clothing, fuel? It is easy, and in one sense inevitable, to fall into a utilitarian-anthropocentric view of the world around us, or else to become super-spiritual and dismissive of the material world.

Historically, the Christian tradition itself has been ambiguous, and we can trace the presence within it of two theological motifs that stand in tension with one another: the spiritual motif in which the human spirit rises above nature in order to ascend to communion with God; and the ecological motif in which the interrelationships between God, humanity, and nature are to the fore.[35]

The ecological motif is present in the writings of the Cappadocian Fathers and within the Celtic and Franciscan traditions, but in Aquinas, a utilitarian anthropocentrism emerges. Aquinas wrote, “lifeless beings exist for living beings, plants for animals, and the latter for man ... the whole of material nature exists for man, inasmuch as he is a rational animal.”[36] Here we see the beginnings of Attenborough’s ‘long shadow’ of Christian acquiescence in creation’s exploitation.

Luther celebrated nature and saw God as wholly and immediately present throughout creation.[37] However, Calvinistic thinking profoundly affected the Reformed view of creation through the doctrine of the fall and original sin.[38] McGrath suggests that this doctrine promoted the idea that disorder in the world is ontologically present[39] and laid the foundation for a view of the non-human creation as fallen and in need of mastery.[40] Furthermore, western science has objectified nature, so that it becomes a human construct with no integrity of its own and it is in danger of being reduced to our own possibilities of studying or using it.[41]

At the same time, Post-Reformation theology has stressed personal salvation from sin and the spiritual motif has predominated. Popular expression of this ‘other-worldly’ theology is reflected in songs such as, “This world is not my home, I’m just a-passing through; my treasures all laid up somewhere beyond the blue.”[42] Tom Wright has brought a necessary refocussing of Christian hope in the renewal of all creation in his book Surprised by Hope,[43] and in a recent Stimulus article Stephen Pattemore grounds our ultimate ecological hope in the biblical meta-narrative – the story of “God’s love for the world from eternity to eternity.”[44] He also draws our attention to proximate hopes for our current situation as we work with people of good will in recognising the significance of interrelationships and the importance of cooperation and community.[45]

Moving back to the biblical text, how is the non-human creation viewed in Revelation? The answer is complex because in Revelation the non-human creation is seen at three different levels: as the background to earthly events, as the symbolic content of John’s visions, and as the eschatological new heavens and new earth.

The non-human creation features prominently in the vision sequences. Sometimes it is perceived as a victim: suffering as a result of human exploitation and greed, particularly in the account of the four horsemen (6:1–8). Or, when it is damaged or thrown out of kilter in actions authorised from heaven – as recorded in the trumpet and bowl judgments (see especially Rev 8:7–12; 16:1–11). However, sometimes the non-human creation is an agent collaborating with God’s purposes. Commenting on the bowl judgments, Tom Wright says, “God will allow the natural elements themselves (earth, sea, rivers, sun) to pass judgment on human beings who have so grievously abused their position as God’s image bearers within creation.”[46] This is an interesting reflection in the light of the human contribution to global warming.

Earth can also be seen as an agent when it refuses to hide fearful humanity (6:16), and when it swallows the dragon’s river to protect the woman (12:16). In addition, the depiction in 6:12 of the sun mourning at the prospect of God’s coming in judgment suggests the rhetorical portrayal of a degree of responsive involvement. In these instances, the non-human creation can be seen to be in a continuing relationship with its Creator with a separate identity and intrinsic worth of its own, rather than merely having an instrumental value as a resource for humanity.

Finally, the non-human creation receives a fresh status as the new heavens and new earth of Rev 21:1 – 22:5. This new order of creation has been described as creation ex vetere (from the old or former) to signify not the annihilation of the old order but its radical transformation and renewal. It most probably contains elements of both continuity and discontinuity with the present creation, but the symbolic nature of John’s vision and the recognition that it deals with a future beyond human experience limits what can be said before moving into the realms of speculation. Nevertheless, certain significant features emerge concerning the non-human creation which I will come back to later.

Human Accountability

We live in an interactive universe in which entities, including humans, do not exist in isolation from their environment. In Revelation this concept of interconnectivity permeates the seal, trumpet, and bowl judgments: human actions adversely affect the non-human creation and humanity is affected by changes in the behaviour of the non-human creation. The latter are depicted as judgments on humanity’s behaviour which suggests that human comportment in relation to both other humans and the non-human creation falls short of what is expected.

In Revelation this falling short is most often identified as idolatry, the worship of someone or something in place of the Sovereign Lord God Almighty, or the refusal to live in his ways. It is to allow Rome or its equivalent to set the standards we live by and the values and attitudes we embrace. Boring pertinently comments that, “[idolatry] refers not only to participation in the idolatrous worship of Roman gods, including the Caesar, but accepting Rome as the point of orientation for life in this world.”[47] Participation will also involve complicity in all that enables Rome to maintain her status and lifestyle. This includes the conquest, oppression, bloodshed, and social and economic injustices represented by the four horsemen (6:1–8), and depicted in John’s vivid and incisive critique of Babylon (Rev 17 – 18).

There is general agreement that John’s visionary account of the fall of Babylon in Rev 17 – 18 is a critique of Rome: its imperial oppression of God’s people, its illusory facade of peace and prosperity, and its dominance of the whole geo-political-economic order. At a referential level this symbolism can be taken to represent the oppressive power of any world government or organisation throughout the ages.[48] Thus, John’s critique of Rome can provide a template for critiquing contemporary socio-economic structures.

Calling the city “the great prostitute” and the interplay of the language of fornication/adultery, wine and intoxication (17:2; 18:3; 14:8) points to the seductive nature of Rome’s allure. Babylon’s promise of economic prosperity is an intoxication: a “magic spell [by which] all the nations were led astray” (18:23d). Even contemporary writers were critical of Rome’s self-indulgent extravagance and ostentatious displays of wealth.[49]

In addition, John is concerned with the exploitive nature of the relationship Rome has with the rest of the empire. Bauckham notes that the basic notion behind John’s description of Babylon/Rome as a prostitute is, “that those who associate with a harlot pay her for the privilege ... Rome is a harlot because her associations with the peoples of her empire are for her own economic benefit.”[50] Vast quantities of wine, oil, flour, and wheat were imported and, as indicated by the third seal judgment, this often led to inflated prices and shortages for those living in the provinces with landowners putting more acreage into higher value crops such as oil and grapes. No ‘fair trade’ deals here!

John’s world of “imperialist politics, global trade, and the murderous oppression of the poor”[51] is very like our own, with affluent western societies consuming a disproportionate amount of the earth’s resources. Moreover, global capitalism has operated on a model that has left Third World countries with an overwhelming burden of debt that is impossible to repay.

But ultimately there is no hope for Babylon (Rev 18:8–20) and John presents his readers with an ethical challenge as he urges them to, “Come out!” (18:4). This is not a geographical relocation but rather an inner reorientation demonstrated by resisting the values of the “Great City,” Babylon, (18:2) and aligning themselves with the coming justice of God in the “Holy City,” the New Jerusalem (21:2).[52]

Similarly, Christians in every age are called to separate themselves from any political-economic system that does not have the well-being of all God’s creation, human and non-human, as its ultimate goal. We must ask ourselves – To what extent have we imbibed the values of the materialistic consumer culture around us? The ‘gods’ of comfort, security, self-fulfilment, together with a ‘bucket-list’ approach to life, have penetrated, largely unnoticed, our faith communities. John’s critique of Rome in Rev 17 – 18 challenges us to examine our own allegiances.

Such attitudes and behaviours contrast with Revelation’s portrayal of God’s interaction with his creation and his grieving over his suffering creation. I began with a verse from Rev 12:12: “Alas for the earth,” which Barbara Rossing asserts is a lament rather than being a pronouncement of woe to the earth; God mourns over the current state of his creation.[53]

It is noteworthy that God displays this level of care and concern for the present creation despite his knowledge that it is going to pass away. It gives us a mandate to pursue eco-justice issues, to take action to prevent environmental abuse even as we recognise that the ultimate righting of wrongs and the right reordering of creation awaits the parousia.

New Creation

However, in Revelation, negative portrayals of the destructive relationships between humanity and the non-human creation are not the last word. Instead, John is given a vision of the new heavens and new earth in which the inter-relationships between God, humanity and the non-human creation, are transformed and restored.

First, John describes a process of de-creation in which all that is opposed to the establishment of God’s universal kingdom is judged (Rev 20:11–15). The old created order has “passed away” (21:1) so that the Creator may effect its eschatological renewal.[54] Then, John describes God’s coming to dwell on earth (21:2–4), a clear counter to the common perception of humanity’s future in a ‘heaven’ that is distinct from earth. Rather, John sees a renewed earth that is suffused with the presence of God in such a way that all space can be said to become sacred space. The focus is at first on the ideal city – the New Jerusalem – but in the latter part of his vision (22:1–5) the focus changes as John introduces Edenic imagery.

Two images dominate this section: the river of life and the tree of life. The river flows from the throne of God through the centre of the city and waters the trees that grow on both sides. They provide sustenance, fruit in abundance – twelve kinds of fruit produced each month – and also leaves for the healing of the nations. Further, the imagery from Ezek 47:1–12 informs our reading of the text. Ezekiel’s river flowed from the temple down to the Dead Sea making it fresh and causing it to teem with life. This picture of a flourishing creation burgeoning with life is a reminder that God’s commands in Gen 1:22, 28 to be fruitful and increase in number have always been integral to his purposes for his creation. In this new creative work God both restores and transforms, surpassing the primordial conditions that characterised Eden, as he brings about what he had always intended for his creation.

Although there is no specific reference to non-human creatures in John’s vision, Duncan Reid suggests that since the city has walls, it has limits, and there is a possibility of a hinterland outside the walls that might be the domain of the non-human creation. He adds, “It is afforded a respectful textual silence in Revelation; this silence underlines that non-human nature is free – it has not been assimilated into the urban, human habitat.”[55] However, ultimately much remains speculative.

The Edenic imagery of 22:1–5 represents paradise restored, not in the sense of a return to the perfection of the first creation after the damage done to it and the curse have been removed (22:3), but rather, Eden as it was intended to be, the unrealised promise of the first creation finally achieved, and the intent inherent in the original placing of humanity as imago dei in Eden comes to fulfilment.

Conclusion

John’s vision presents a reality that is not yet apparent in all its fullness, but which has the capacity to shape our attitudes, values, and goals. We are familiar with the idea that we work for social justice and for the redemption and healing of humanity as we look for God’s kingdom to come in all its fullness. As Christ’s disciples, let us act that way toward the non-human creation as we await its future transformation.

My hope is that these insights derived from an eco-critical reading of Revelation might encourage us to pursue an holistic discipleship that is more than a response to current crises but rather is a participation in the mission of God – for the gospel is God’s good news not only for humanity but for all of creation.

I want to end with a reminder of the scene in Rev 5:13–14 where we are given a proleptic vision of the whole of creation, all creatures in every conceivable environment, human and non-human; earthly and heavenly, bowing in worship before the throne.

Then I heard every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth and on the sea, and all that is in them, saying:

‘To him who sits on the throne and to the Lamb

be praise and honour and glory and power,

for ever and ever!’

The four living creatures said, ‘Amen,’ and the elders fell down and worshipped.

Jean Palmer is an adjunct tutor at Bishopdale College. Jean has a BA Hons degree from London University and Bachelor and Master’s degrees in Theology from Laidlaw College. Jean is also Priest Assistant at Holy Trinity Anglican Church, Richmond. She and John have three adult children and four grandchildren.

[1] Rev 12:12: ouai tēn gēn – “woe to the earth.” See Barbara R. Rossing, “Alas for Earth! Lament and Resistance in Revelation 12,” in The Earth Story in the New Testament, The Earth Bible Vol 5, eds. Norman C. Habel and Vicky Balabanski (London: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002), 180.

[2] Daniel Carrington, “The Anthropocene epoch: scientists declare dawn of human influenced age.” http://www.the guardian.com/environment/2016/aug/29/declare-anthropocene-epoch-experts-urge-geological congress-human –impact-earth.

[3] All these issues are discussed in detail in Steven Bouma-Prediger,For the Beauty of the Earth: A Christian Vision for Creation Care,2nd ed.(Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2010), 23–56. See also Pope Francis, Laudato Si’, Praise be to You,: On Care for Our Common Home (San Francisco: Ignatius Press 2015), paragraphs 17–61.

[4] This possibility was suggested in a 2007 article by Rafael Reuveny, “Climate Change-Induced Migration and Violent Conflict,” Political Geography 26 (2007): 656–73.

[5] Lynn White Jr., “The Historical Roots of our Ecologic Crisis,” Science 155, No.3767 (March 10, 1967): 1203–1207.

[6] Sir David Attenborough, “I’d Show George Bush a Few Graphs,” in Natural World (2005): 18.

[7] The exercise of guardianship and stewardship by the tangata whenua (the local Māori people) of an area in accordance with tikanga Māori (Māori customs and protocols) in relation to natural and physical resources. It is concerned with both sustainability of the environment and the utilisation of its resources.

[8] To introduce a rāhui is to put in place a temporary ritual prohibition, such as a closed season, or temporary ban. Traditionally, a rāhui was put in place as a conservation measure or to accord with social customs and beliefs.

[9] They were first developed as four marks by the Anglican Consultative Council (ACC-6) in 1984. See Bonds of Affection (ACC-6, 1984), 49. A fifth was added in 1990 as the missiological and biblical implications of the creation and environmental crisis was appreciated. See Mission in a Broken World, (ACC-8, 1990), 101.

[10] A term employed by John Paul II in his General Audience on Wednesday 17th January 2001 https://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/audiences/2001/documents/hf_jp-ii_aud_20010117.html. It is explored further by Pope Francis in Laudato Si’ especially para 217–21.

[11] Pope Francis, Laudato Si’ Para 217. For a NZ perspective see Bishop Peter Cullinan, “Moving Beyond Normal: A Roman Catholic Perspective on the Ecological Crisis.” Stimulus 20, 1 (April 2013): 13–16.

[12] Stewardship has been described as the default model for many evangelicals. R. J. Berry, Environmental Stewardship: Critical Perspectives – Past and Present (London: T&T Clark, 2006), 5.

[13] For a more detailed account see Christopher H. J. Wright, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God (Downers Grove IL: Inter Varsity Press, 2004), 183, 184, 196. Also Hilary Marlow, Biblical Prophets and Contemporary Environmental Ethics: Re-reading Amos, Hosea, and First Isaiah (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 111.

[14] Richard Bauckham, The Bible and Ecology: Rediscovering the Community of Creation (Waco TX: Baylor University Press, 2010), 146–47.

[15] This concept is a valuable corrective to traditional anthropocentric models. See Richard Bauckham, “The Community of Creation,” in Bauckham, Bible and Ecology, 64–102.

[16] Lynne M. Baab, “Character and Practices that Nurture Creation Care,” Stimulus 20, 1 (April 2013): 19–23; Chris Naylor, “What Does It Mean To Save a Marsh?” Stimulus 20, 1 (April 2013): 25–27; Kristel Van Houte, “Restoring Karioi Maunga.” Stimulus 20, 1 (April 2013): 29–31.

[17] For example, Rom 8:19–23, although its contribution to ecotheology and ethics is less obvious and more problematic than is generally assumed. David G. Horrell, Cherryl Hunt and Christopher Southgate, Greening Paul: Rereading the Apostle in a Time of Ecological Crisis (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2010), 65–85.

[18] Norman Habel, An Inconvenient Text: Is a Green Reading of the Bible Possible? (Hindmarsh, South Australia: ATF Press, 2009), 33.

[19] This is particularly true in the United States. See Henry O. Maier, “There’s a New World Coming! Reading the Apocalypse in the Shadow of the Canadian Rockies,” in Habel and Balabanski, The Earth Story in the New Testament, 171.

[20] Issues surrounding the language used in translating eschatological imagery in both Revelation and 2 Peter can be found in Stephen Pattemore, “How Green is your Bible? Ecology and the End of the World in Translation,” The Bible Translator 58, 2 (April 2007): 75–85. See also Edward Adams, The Stars Will Fall from Heaven: Cosmic Catastrophe in the New Testament and its World (London: T&T Clark, 2007) for an excellent, detailed explication of this topic.

[21] Timothy Clark has defined ecocriticism as: “a study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment, usually considered from out of the current global environmental crisis and its revisionist challenge to given modes of thought and practice.” Timothy Clark, Cambridge Introduction to Literature and the Environment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), xiii.

[22] Rev 4:8, 11; 6:9; 7: 11–12; 11:13, 17; 15:3: 16:7; 18:8 and 19:6.

[23] Rev 6:1; 8:2; 15: 6–7.

[24] Alister E. McGrath, A Scientific Theology, Vol.1 Nature (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2001), 81–134.

[25] David E. Aune, Revelation 1–5, WBC 52A, (Dallas: Word, 1997), 312.

[26] NIV.

[27] AV, RSV, NRSV, ESV, NEB.

[28] Ē archē tēs ktiseōs tou Theou.

[29] See also 2 Cor 5:15, 17 where Paul links Jesus’ death and resurrection with new creation.

[30] Denis Edwards, Partaking of God: Trinity, Evolution and Ecology (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2014), 64.

[31] Thomas Torrance, The Christian Doctrine of God: One Being Three Persons (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1996), 244.

[32] Denis Edwards, Ecology at the Heart of Faith (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2006), 76.

[33] Niels Gregersen, “The Cross of Christ in an Evolutionary World,” Dialog: A Journal of Theology 40, 3 (2001): 192–207.

[34] John Polkinghorne offers useful insights on the possible nature of this transition in his book The God of Hope and the End of the World (New Haven/London: Yale University Press/SPCK, 2002).

[35] H. Paul Santmire, The Travail of Nature: The Ambiguous Ecological Promise of Christian Theology (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1985), 9, 21–23.

[36] Thomas Aquinas Summa Theologica 1. Q.96, Art. 1; Compendium of Theology, 1, 148.

[37] Heinrich Bornkamm, Luther’s World of Thought, trans. Martin Bertram (St Louis: Concordia, 1958), 189.

[38] Calvin wrote: “For ever since man declined from his high original state, the world necessarily and gradually degenerated from its nature.” John Calvin, Genesis, The Crossway Classic Commentaries eds. Alister McGrath and J. I. Packer (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2001), 30.

[39] Alister McGrath, The Re-enchantment of Nature: Science, Religion and the Human Sense of Wonder (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2002), 174–76.

[40] “Man by the Fall fell at the same time from his state of innocence and from his dominion over nature. Both of these losses, however, can even in this life be in some part repaired; the former by religion and faith, the latter by the arts and the sciences.” Francis Bacon, Novum Organum Aphorisms Book II, LII (1620), ed. Joseph Devey (New York: P.F. Collier, 1902). https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/bacon-novum-organum.

[41] Bruce V. Foltz and Robert Frodeman, Rethinking Nature: Essays in Environmental Philosophy, (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2004), 330–31.

[42] Songwriter: Mary Reeves Davis, This World Is Not My Home lyrics © Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC.

[43] Tom Wright, Surprised by Hope, London: SPCK, 2007.

[44] Stephen Pattemore, “Sustained by Hope.” Stimulus 20, 1 (April 2013): 42–49. This issue of Stimulus contains further articles on a biblical approach to ecology and the eschatological hope for the groaning creation.

[45] Ibid., 44–46.

[46] Tom Wright, Revelation for Everyone (London: SPCK, 2011), 142.

[47] M. Eugene Boring, Revelation (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1989), 180 (my emphasis).

[48] G. K. Beale, The Book of Revelation, NIGTC (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 869.

[49] See J. Nelson Kraybill, Apocalypse and Allegiance: Worship, Politics and Devotion on the Book of Revelation (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2010), 141.

[50] Richard Bauckham, The Climax of Prophecy: Studies on the Book of Revelation (London: T&T Clark, 1993), 346–7.

[51] Allen Dwight Callahan, “Babylon Boycott: The Book of Revelation,” Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology 63, 1 (2009): 51.

[52] This is more thoroughly explored in Barbara Rossing, The Choice Between Two Cities: Whore, Bride, and Empire in the Apocalypse (Harrisburg: Trinity Press International, 1999.)

[53] Barbara Rossing, “Alas for Earth! Lament and Resistance in Revelation 12,” 180.

[54] Richard Bauckham, The Theology of the Book of Revelation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 48–50.

[55] Duncan Reid, “Setting Aside the Ladder to Heaven: Revelation 21:1–22:5 from the Perspective of Earth,” in Readings from the Perspective of Earth, The Earth Bible Vol. 1. Edited by Norman C. Habel. (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 2000), 244.

Gallery