Pastoral Care from Prison

On Monday 23 March, the New Zealand government announced that the country was in Alert Level 3 and with forty-eight hours’ notice, would go to Alert Level 4.

The nation would be in lockdown for at least four weeks. There was a tiny window of opportunity to set-up workspace at home and anticipate the resources needed for at least one month’s work.

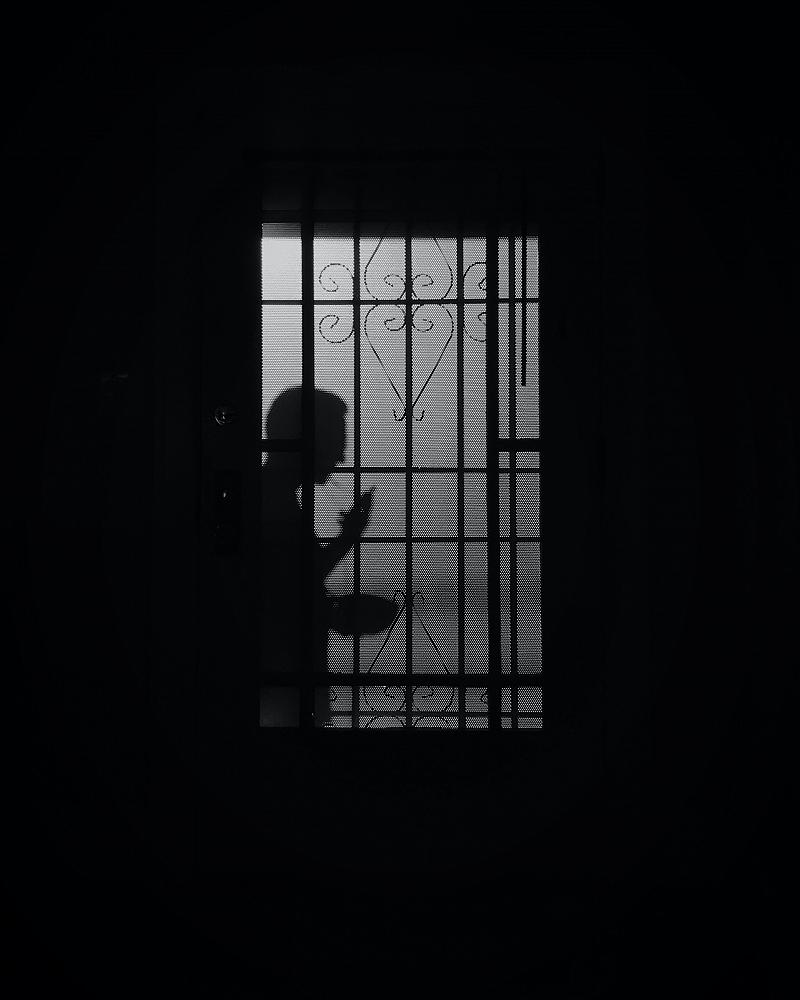

My role as Dean of Studies at the Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership (Dunedin) entails being part of the team facilitating the training and formation of Presbyterian ministry interns. The ministry interns are in various church contexts. Some are in sole-charge positions and others are in team settings. Like Christian leaders across the nation, the overnight question was, “How do I lead and provide pastoral care from a place of isolation to those in isolation?”

My mind went to the Letter to the Philippians. I decided to write a reflection and guidelines to help the ministry interns. However, because of the short timeframe before the lockdown took effect, I had not brought all the resources I needed into lockdown. So, I wrote the following reflection relying on my memory of reading Gordon Fee’s commentary on Philippians[1] twenty-five years ago. Fortunately, I had some notes saved on my computer from Fee’s thoughts on Philippians 4.

So, this reflection is offered as an artifact from the lockdown written with limited resources. From my “prison,” I can relate to Paul’s plea from prison for more resources: “When you come, bring … the books, and above all the parchments” (2 Tim 4:13). Yet, COVID-19 has imprisoned us, and we find ourselves needing to draw on whatever resources are at hand.

Providing Pastoral Care from Isolation to Those in IsolationThe Letter to the Philippians

Philippians is one of the seven prison letters written by Paul.[2] The precise locations where Paul was imprisoned for each of the letters is not certain. While Rome is the favoured location, some, or all of them, may have been Caesarea or Ephesus also.

The appeal of using one of the prison letters as a basis for reflection is the common denominator of confinement and restriction on freedom of movement. However, we need to acknowledge that Alert Level 4 lockdown is qualitatively different to first-century imprisonment for someone facing martyrdom. We have the freedom of leaving our “prison” for a walk or to buy food, and we have access to entertainment and medical assistance, should we require it. Also, we are likely to be in Alert Level 4 for weeks, whereas, on some occasions, Paul was imprisoned for years. Yet for all the marked differences, Scripture provides a voice and vision to help us at this time.

One way in which Philippians provides voice is by highlighting Paul’s spirituality. Throughout his letters, the same spirituality is evident: faith in Christ marked by thanksgiving, prayer, peace, and joy. This is especially so in Philippians. As we find ourselves in a level of isolation marked by great uncertainty, practices, and dispositions of thanksgiving, prayer, peace, and joy can be elusive. Philippians speaks to our condition so we can provide pastoral care and spiritual leadership from isolation.

One way that Philippians provides us with a vision for Christian life is by highlighting a range of theological themes and issues in the Philippian church. However, one major undercurrent influences it all—friendship. In the first century, there were strong cultural practices concerning how friendships operated. One key aspect was the glue of friendship was reciprocity. If you did something for me, first-century friendship etiquette obligated that I do something for you. For Paul, as someone in enforced isolation, this was a major problem. The Philippian church had sent him a gift to meet his needs and Paul could not reciprocate. He could not honour his part in the friendship. As a pastoral leader, there are natural expectations in how you honour your part in the pastoral relationship however your current confinement inhibits that. Philippians opens our eyes so we can provide pastoral care and spiritual leadership from isolation.

In addition to these considerations, the backdrop of Philippians is the concern raised by the life-threatening illness suffered by Epaphroditus. Epaphroditus had been sent by the Philippian church to Paul with a gift (Phil 2:25-30). However, while attending to this task, Epaphroditus had fallen gravely ill and nearly died. He recovered by the mercy of God (Phil 2:27).

But everyone involved was anxious.

- The Philippian church was anxious because they heard Epaphroditus was ill (Phil 2:26).

- Epaphroditus was anxious because the Philippian church was anxious about him (Phil 2:26).

- Paul had been anxious Epaphroditus would die (Phil 2:27).

- Paul was anxious to ensure the church and Epaphroditus were reunited (Phil 2:28).

As we endeavour to minister in the midst of a pandemic, we can suffer anxiety that is both clearly identified and hard to define. Anxiety itself is a virus, infecting people’s hearts and minds. Clarity, certainty, and confidence evaporates. The world is unsafe and even threatens to harm those people we depend and rely on.

Such are some of the contours of the space from which we are now called to provide pastoral ministry.

Providing Pastoral Care

From his place of isolation, Paul provides wonderful examples of how we might provide pastoral care and leadership from our imprisonment.

Phil 4:4–20 is my chosen text.

1. The Same as Psalms (Phil 4:4–7)

4 Rejoice in the Lord always. I will say it again: Rejoice! 5 Let your gentleness be evident to all. The Lord is near. 6 Do not be anxious about anything, but in every situation, by prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, present your requests to God. 7 And the peace of God, which transcends all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.[3]

This section echoes the words, movement, and spirit of the Psalms. Specifically, an honest acknowledgement that suffering is real … and so is God. These words from Phil 4:4–7 also model another crucial feature of the Psalms—the movement from the individual to community. Each person has relationship and responsibilities before God and this feeds into the whole community.

Paul lists several do-this-and-do-that instructions. He draws on one of the enduring legacies from the Old Testament; “devotion and ethics are inseparable responses to grace.”[4] And all of this is heavily seasoned by the call to joy. For Paul—joy and peace are intertwined.

Put another way, “God’s peace is joy resting. God’s joy is peace dancing.”[5]

With this comes is a hope-filled distinct Christian declaration: “The Lord is near” (v 4). This has a double meaning. The Lord is near now. The Lord will be near then, in the age to come.

The Lord is near now. The Lord is Emmanuel—God with us.

The Lord will be near then. The Lord has an eschatological intention—he will return as he promised and create a new heavens and new earth.

Combating COVID-19 with Phil 4:4–7

When we communicate with those under our pastoral care:

- Let your gentleness be evident.

- Model reliance and faith in God by drawing on appropriate words from Scripture.

- Speak words of hope grounded in the person and work of Christ.

- Offer to prayerfully present people’s requests to God with them.

- Remember—all of this is done in a spirit of friendship.

2. The Search for Wisdom (Phil 4:8–9)

8 Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable—if anything is excellent or praiseworthy—think about such things. 9 Whatever you have learned or received or heard from me, or seen in me—put it into practice. And the God of peace will be with you.

This list in verses 8 to 9 draws on the world in which Paul and the Philippians lived. While these verses are often quoted as “think about,” the Greek term has its background in accounting and so it is more accurate to read these verses as saying, “take into account.”[6] This is a strong and particular encouragement from Paul. His words draw both on the culture of the day and Jewish wisdom, and then Paul wordsmiths it in the light of what it means to be a disciple of Jesus. What begins as a list that mirrors Greco-Roman culture and Jewish wisdom, ends as something distinctly Christ-centred and a stand-out list both for antiquity and life today.

What is noticeable here is the two words “whatever” and “anything.” This is an exercise of searching, considering, choosing, selecting, and discerning—this is a world-wide treasure hunt for whatever/anything that is excellent or praiseworthy.

Although it may be stretching the friendship aspect of the letter, one might suggest that to continue the friendship flavour of Philippians, Paul is making friends with the best parts of the world the Philippians live in. Yet, this is not to suggest a wholesale and unthinking embrace of the world. As Paul writes, they are children of God in the midst of a crooked and warped generation (2:15). Paul provides a vital caveat and personifies it in his lived example—a life shaped by the cross is all important. So, the first part (v. 8) is: “Take into account the best the world has to offer.” The second part (v. 9) is critical: “Take into account how I, your pastoral leader, have done this same exercise in light of the cross.”[7]

Combating COVID-19 with Phil 4:8–9

When we communicate with those under our pastoral care:

- Highlight the wisdom of the experts’ (health officials and government) advice and measures.

- Encourage people, as ambassadors of Christ, to seriously take such important measures into account. They have a Christian ethical responsibility to do so.

- Model the culling of unhelpful, alarmist, ill-informed, or unsafe advice/information on social media.

- Help people to discern the goodness of God in the words and actions of skilled people who have trained and prepared for this kind of global crisis.

- Highlight joy-filled and life-giving suggestions from whatever source that helps people in their isolation.

3. The Source of Strength (Phil 4:10–13)

10 I rejoiced greatly in the Lord that at last you renewed your concern for me. Indeed, you were concerned, but you had no opportunity to show it. 11 I am not saying this because I am in need, for I have learned to be content whatever the circumstances. 12 I know what it is to be in need, and I know what it is to have plenty. I have learned the secret of being content in any and every situation, whether well fed or hungry, whether living in plenty or in want. 13 I can do all this through him who gives me strength.

Paul’s imprisonment and the geographical distance from the Philippians raised concerns that their relationship/friendship could not bridge the gulf in practical ways. The circumstances were such that the opportunity to practically care for one another quickly was not possible. Epaphroditus’s journey to Paul showed it was possible to care to a degree but not to the extent that either the church in Philippi or Paul would have ideally liked.

What to do? What to say?

Paul again brings the raw materials of faith in Christ and the faithfulness and nearness of God to bear on the situation. He describes in stark terms the contours of life. Yet, for him, quality of life is not measured by what he does or does not have; it is measured by what Christ gives him to cope. There is no suggestion that this is a quick and easy process. It is one that Paul had to learn. Yet, he can say with confidence that in the absence of the means to serve each other—and fulfil their obligations as friends—he is empowered by Christ who gives him strength (cf. Matt 11:28–30).

Combating COVID-19 with Phil 4:10-13

When we communicate with those under our pastoral care:

- You may discover people are concerned for your welfare—and they feel guilty they cannot do more for you.

- When Paul encountered such concern, his response modelled an honest description of life and a robust trust in God. What will your honest and heart-felt response be?

- Paul’s response also modelled an offering from his own journey of faith. His words are reassuring and faith-full. What can you offer by way of reassurance and faith-full words when people are feeling so awful that they cannot do more for you?

4. The Sacrament of Spaces (Phil 4:14–20)

14 Yet it was good of you to share in my troubles. 15 Moreover, as you Philippians know, in the early days of your acquaintance with the gospel, when I set out from Macedonia, not one church shared with me in the matter of giving and receiving, except you only; 16 for even when I was in Thessalonica, you sent me aid more than once when I was in need. 17 Not that I desire your gifts; what I desire is that more be credited to your account. 18 I have received full payment and have more than enough. I am amply supplied, now that I have received from Epaphroditus the gifts you sent. They are a fragrant offering, an acceptable sacrifice, pleasing to God. 19 And my God will meet all your needs according to the riches of his glory in Christ Jesus. 20 To our God and Father be glory for ever and ever. Amen.

These words in Phil 4:14–20 turn up the volume of what friendship looked like in the first century and the dilemma Paul faced. He had been in need, and the church of Philippi responded with generosity and faithfulness. They define the best aspects of friendship—but because he is in prison Paul cannot uphold his part in the relationship.

His response is to hand it over to God. Paul sees the work and presence of God in the gaps and deficits in the friendship. Paul has some practical obligations but, in the spaces, where he cannot fulfil those—he genuinely and sincerely makes it, to put it metaphorically, sacramental. He commends the Philippians to God’s action and giving and commits God to act on Paul’s behalf: “Your will be done on earth as it is in heaven.” The Philippians give Paul gifts delivered by Epaphroditus and Paul re-gifts them, figuratively speaking, as a sacrament. A sacrament in the sense that physical items and practical actions convey a deep and rich spiritual reality:

“They [the gifts] are a fragrant offering, an acceptable sacrifice, pleasing to God” (Phil 4:18).

Paul cannot fill the space with a gift of his own—as the Greco-Roman culture would demand —so he draws on the reality of God’s activity which blesses his brothers and sisters in Christ:

“And my God will meet all your needs according to the riches of his glory in Christ Jesus” (Phil 4:19).

Combating COVID-19 with Phil 4:14-20

When we communicate with those under our pastoral care:

- Consider how you might re-interpret the spaces (gaps and deficits) people feel acutely in their lives. Such spaces can be distressing for people. They might feel burdened they cannot fulfil what they perceive as obligations to family, friends, neighbours, or their church family.

- Listen carefully to them. As they talk – can you punctuate their words with phrases such as “Pleasing to God …” and “My [their] God will …”

- When you identify a space in someone’s life – rewrite Phil 4:19 to create a sacrament for their particular situation.

- “To our God and Father be glory for ever and ever. Amen.” (Phil 4:20).

[1] Gordon Fee, Paul’s Letter to the Philippians NICNT (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995).

[2] The other three are Ephesians, Colossians, Philemon, and the Pastorals which were also written from prison.

[3] All citations from NIV, 2011.

[4] Fee, Philippians, 402.

[5] This quote is frequently attributed to F. F. Bruce but is also found in the writings of C. S. Lewis and likely originated with F. B. Meyer. A version also appears in C. H. Spurgeon, “A Round of Delights” in The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit Sermons. Vol. 23. (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1877), 642. It may have originated in Meyer who was contemporaneous with Spurgeon.

[6] See meaning 1 in BDAG 597–98: “to determine by mathematical process, reckon, calculate.”

[7] The throbbing heart of Philippians is the majestic hymn in Phil 2:5–11. The whole letter must be read with these words in mind. There is the vision of the person and work of Christ in the midst of the world that the Philippians lived in then and the world we live in now.

Geoff New is Dean of Studies at the Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership (Dunedin). He is a trainer for Langham Preaching in South Asia. He also leads Kiwimade Preaching. His doctoral research explored the impact of utilising Lectio Divina and Ignatian Gospel Contemplation when preparing sermons.