Hearts and Minds: Inside and Outside the Fences

Spirituality, Sheldrake suggests, is one of those subjects “whose meaning everyone claims to know until they have to define it.”[1]

Attempts to pin it down vary depending on whether the definer is approaching the challenge from a religious or a secular standpoint, and on their particular traditions and interests. My stance here is unashamedly Christian, and my interest is in the work of spiritual care (primarily as a spiritual director). In that field I find myself in conversation with people of all shades of religious tradition and none. The thoughts offered here are my attempt to make meaning of those broad ranging conversations within my own explicitly Christian understandings of spirituality.

Within the field of spiritual care, practical theologian John Swinton compares generic approaches to spirituality with those that are explicitly religious.[2] By generic approaches, he means those which assume “the person is in essence spiritual, irrespective of their involvement or otherwise in formal religion.” These approaches view spirituality as relating to issues of meaning, purpose, value, hope and love.[3] Religious approaches, on the other hand, generally include an emphasis on transcendence, that is, an experience of something beyond materiality, whether or not that something is thought of as a divine being.[4]

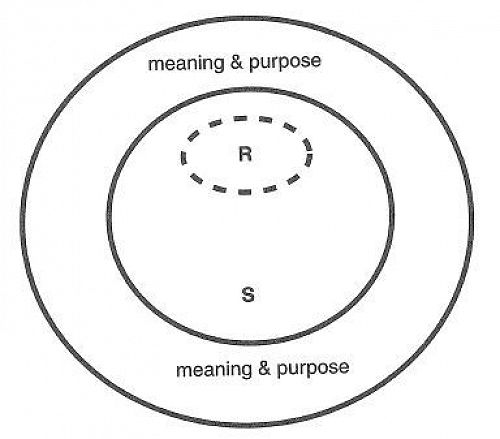

The last two decades have seen an increasing interest in spirituality within the caring professions.[5] Prior to this, as Holloway and Moss observe in relation to social work, there had been a lot of suspicion towards religion.[6] This was due in part to the religious origins of social work and the battle people had fought to establish it as a credible secular academic discipline. Consequently, in this and other caring professions, there has been a search for generic rather than religious understandings and definitions of spirituality. Indeed, Holloway and Moss argue that “a secular spirituality without a belief in a divine Being can have just as powerful a validity and value as a religious spirituality.”[7] For the purposes of spiritual care, they propose that spirituality needs to be an inclusive concept “that touches the lives of everyone by raising issues that illuminate what it means to be human, and includes, but is not constricted by, religious world-views.”[8] They offer a diagram in which ‘S’ represents an inclusive understanding of spirituality, which incorporates, but is not restricted to, a religious world-view (‘R’).[9] So while the religious dimensions to spirituality are included, “the secular dimensions are much broader and all-encompassing.”[10] These broader dimensions of spirituality are in turn understood in terms of the human search for meaning and purpose. (See image below)

Given the suspicion toward religion which Holloway and Moss encounter within their discipline, perhaps we should be grateful that they reserve a space, albeit a limited one, for explicitly religious understandings of spirituality. Given that this includes all religions, the space for Christian forms of spirituality is smaller still. Meanwhile, in the ‘S’ space, new forms of non-religious spiritual care are burgeoning alongside the traditional chaplaincy model. Interfaith chaplaincy is not new, but now the case for secular and even atheist chaplains is being argued.[11]

Rather than feeling grateful, however, I suspect that some Christian spiritual carers will feel marginalised by, and wary of, these broader approached to spirituality. They are moving into a neighbourhood which for centuries we claimed as our own. As someone who is interested in spirituality and spiritual care, I certainly resist the prospect of occupying an ever shrinking space reserved for people with explicitly religious (and, by implication, arcane) beliefs.

My resistance is supported by two convictions. First, while the number of people who claim to be SBNR (spiritual but not religious) may be increasing, this does not render the wisdom and experience of those in the ‘R’ space irrelevant. Swinton challenges the perception that personal religious inclinations are dying out, while accepting that there is certainly a reaction against formal religious structures. Spirituality may be an expansive concept, but it is worked out in practice through the particularities of people’s lives, and many people still reach into religious traditions to do that.[12]

Religion, Swinton argues, “provides a powerful worldview and a specific epistemological and hermeneutical framework within which people seek to understand, interpret and make sense of themselves, their lives and their daily experiences in sickness and in health.”[13] High quality person-centred care therefore needs to include attention to what religion means to care-seekers, however the care-givers position themselves in relation to religious belief.[14] Religious traditions also include symbolic modes of expression – rituals, prayers and worship – which can play a powerful role in spiritual care.[15] If the ‘R’ space is understood as referring not to institutionalised religion, but to the rich resources of the spiritual traditions of religious faith, then it may be considered to be a wellspring for the broader ‘S’ space, rather than an esoteric enclave.[16]

The second conviction which fuels my resistance to being fenced into a restricted ‘R’ zone is theological. Rather than feeling threatened by conversations with people who hold very broad or generic ideas about spirituality, I often feel excited. Why? Because in my mind, stirrings of positive spiritual interest and a quest for meaning and purpose may well be evidence of the Spirit at work. So I want to turn the above diagram inside out. God is not limited to the ‘R’ zone, nor the ‘S’ zone. Rather, all is located in God, in whom “we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28). Holding this conviction is not, for me, about reasserting a religious hegemony in the field of spiritual care, but about entering that field with openness and expectancy as to what the Spirit is up to, even where God is not acknowledged.

My spirituality, together with my role as a spiritual carer, is anchored in a belief that God is not remote from creation or us as creatures, but is actively and dynamically present. As trinitarian theologian Paul Fiddes argues:

[O]ur experience of ourselves and others must always be understood in the context of a God who is present in the world, offering a self-communication which springs from a boundless love. It is this self-gift of God which already shapes both our experience of being in the world and our language with which we configure our experiences.[17]

For Fiddes, God is not "one person" and at the same time "three persons," in the usual sense of individual persons. Rather, the primary reality in God consists of the relations or relational movements within God, and the primary mode of experiencing God – not just for people of faith, but for all persons – is participation in these movements within God. An experience of the divine is therefore not so much an ‘I-Thou’ encounter with one personal being, or three personal beings, as it is a participation “in a flow of personal relationships in God which are like ‘movements between’ an I and Thou.”[18]

My desire to turn the above diagram inside out resonates with Fiddes’ belief that God’s presence and movement are to be discerned not only in the traditional religious sacraments, but in “the whole body of the world.”[19] He cites Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem ‘”As Kingfishers Catch Fire,” in which each thing in creation has its own unique identity and vocation and at the same time participates in Christ’s playful response to the Father through creation:

For Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men’s faces.[20]

As a spiritual carer, then, it is these movements in myself and others – traces of the trinitarian dance[21] – which I hope to notice and cooperate with. For, says Fiddes,

if we notice what is particular about others, and are alert to what is unexpected there, we will see people’s value as images of God, as playgrounds for the Spirit. This will lead to our having hope for them, to believing that change is possible and that they are not fated to repeat past patterns of self-destruction.[22]

This, then, is why I won’t limit my sphere as a Christian spiritual carer to part of a small dashed circle labelled ‘R.’ Each person and relationship I encounter is potentially a playground of the Spirit, and the Spirit, as James K. Baxter’s Song to the Holy Spirit reminds us, blows “like the wind in a thousand paddocks/Inside and outside the fences/You blow where you wish to blow.”[23]

David Crawley lectures in spirituality and pastoral care at the Henderson campus of Laidlaw College. Alongside this role he works as a spiritual director and supervisor, and contributes to the life of his local Anglican church in Titirangi as a non-stipendiary priest.

[1] Philip Sheldrake, Spirituality and History: Questions of Interpretation and Method (London, UK: SPCK, 1996), 40.

[2] John Swinton, "The Meanings of Spirituality: A Multi-Perspective Approach to 'the Spiritual'," in Spiritual Assessment in Healthcare Practice, ed. Wilfred McSherry and Linda Ross (Keswick, CA: M & K Publishing, 2010).

[3] Ibid., 18.

[4] Ibid., 26.

[5] See, for example, Mark Cobb, Christina M. Puchalski, and Bruce D. Rumbold, eds., Oxford Textbook of Spirituality in Healthcare (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2012).

[6] Margaret Holloway and Bernard Moss, Spirituality and Social Work (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 23.

[7] Ibid., 28.

[8] Ibid., 29.

[9] Ibid., 30.

[10] Ibid., 29.

[11] Mark Kolsen, "Atheist Hospital Chaplains: The Time Has Come," American Atheist 55, no. 2 (2017).

[12] Swinton, in Spiritual Assessment in Healthcare Practice, 25.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., 28.

[15] See James L. Griffith and Melissa Elliott Griffith, Encountering the Sacred in Psychotherapy: How to Talk with People About Their Spiritual Lives (New York: Guilford Press, 2003).

[16] Perhaps the authors hint at this by drawing a dashed boundary around the ‘R’ zone.

[17] Paul S. Fiddes, Participating in God: A Pastoral Doctrine of the Trinity (London, UK: Darton, Longman and Todd, 2000), 8.

[18] Ibid., 279.

[19] Ibid., 283.

[20] Ibid., 290. Eugene Peterson also draws on this poem in his Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places: A Conversation in Spiritual Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008).

[21] C. Baxter Kruger, The Great Dance: The Christian Vision Revisited (Jackson, MI: Perichoresis Press, 2005).

[22] Fiddes, 301.

[23] James K. Baxter, "Song to the Holy Spirit," in James K. Baxter: Collected Poems, ed. Jonathan Weir (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1979), 572.

Gallery