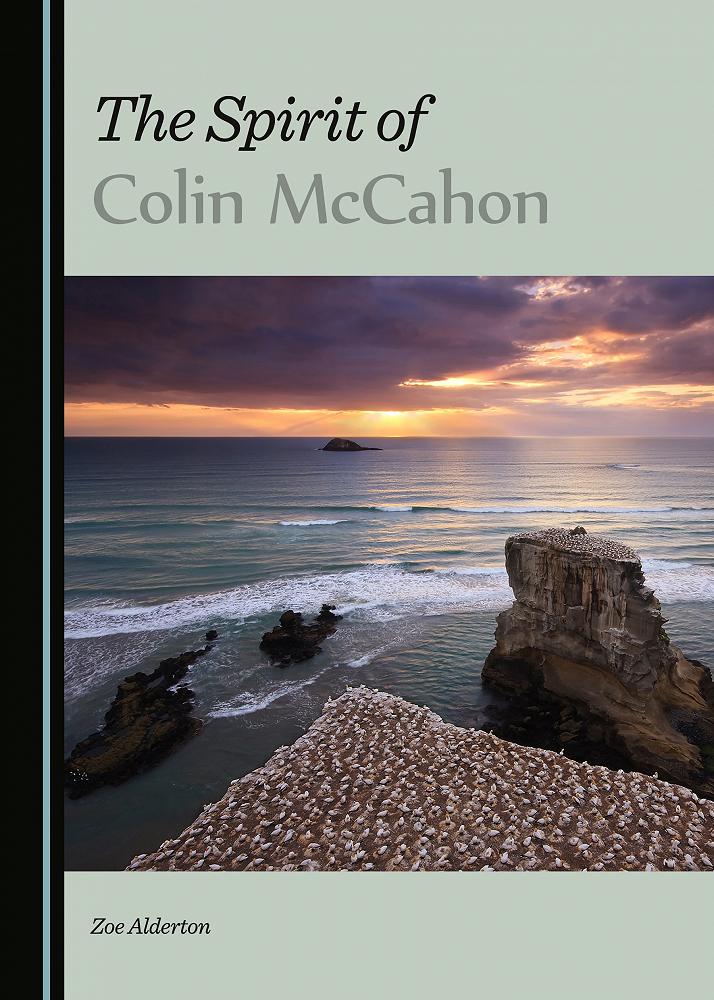

Book Review: The Spirit of Colin McCahon*

Zoe Alderton

It was Colin McCahon’s destiny to be a Christian artist in a secular culture, where his primary themes were constantly sidelined, ignored or misunderstood by the art world and the academic community. As Alexa Johnston, a close friend and author of one of the earliest assessments of the religious significance of his work, wrote for a 1966 exhibition of his paintings in the Manawatu Art Gallery:

Colin McCahon’s works have in recent years achieved acceptance and acclaim in the New Zealand and Australian art markets. They are high status commodities. Yet their religious content is seldom discussed, either critically, or I imagine, around the diner tables of their owners…. There is a nagging suspicion that McCahon has somehow let us down by his being a great painter, yet insisting on “bringing religion into it.”

The publication of a full-length book devoted specifically to the religious dimension of Colin McCahon’s art is therefore a most welcome development. Zoe Alderton is to be commended for her diligent research and encyclopedic documentation of this foundational theme in McCahon’s life and work. The book is based on her PhD thesis at the University of Sydney (2013). Its academic origin is both a strength and a weakness. It is exhaustively documented, but the documentation threatens at times to overwhelm the telling of the story and the clarity of its themes. It is a pity that there are no pictures and no index.

Alderton quotes my assessment that “McCahon’s greatest contribution was to contextualise a Judaeo-Christian vision in New Zealand art” (45). As Marja Bloem says in Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith, the book of the comprehensive exhibition of McCahon’s paintings that showed in the Auckland Art Gallery in 2003, “landscape and religion… are constant factors in his life and work” (16). This exhibition was the first to give international recognition to the leading New Zealand artist for grappling with the religious and existential questions of our secular age. In this McCahon is without parallel in the second half of the twentieth century. He invites comparison with the French Catholic painter Georges Rouault (1871-1958), during the dehumanising events of the first half of that century.

Alderton’s work focuses on the discrepancy between McCahon’s direct and sometimes aggressive religious intentions and the reception that he received. “McCahon’s religious content is a major factor in his disappointing reception,” she says. “Ranging from suggestions that Christianity is an affront to the secular gallery space to the belief that his artworks have transcended commercial value, McCahon’s imagery has sparked a plethora of divergent anxieties in relation to its religious motifs and messages…. He was distressed by a lack of understanding of his vision, which he perceived to be a failure of his art” (1).

Alderton discusses McCahon’s Christianity in the context of the New Zealand “Nationalist Project” – the name given to poets like Allen Curnow and literary critics like Charles Brasch who sought to give New Zealand literature a specific indigenous voice over against its colonial inheritance as an intellectual outpost of Great Britain. His famous early painting “The Promised Land” (1948) illustrates this commitment. McCahon (1919-87) grew up in Maori Hill Presbyterian Church. His wife Anne was the daughter of Anglican Archdeacon W. A. Hamblett. He was attracted by the pacifism of the Quakers, but swayed by the moral claims of the war against Nazism. In the nineteen-sixties he was stimulated by friendships and intellectual companionship in the Catholic Church, and undertook a number of Catholic commissions. But he never formally joined the Catholic Church.

Alderton cites a childhood vision that McCahon had while on a drive with his family on the Taieri:

"Big hills stood in front of the little hills, which rose up distantly across the plain from the flat land: there was a landscape of splendour, order and peace….

I saw something logical, orderly and beautiful belonging to the land and yet not to its people…. My work has largely been to communicate this vision and to invent the way to see it" (28).

In McCahon’s landscape paintings we see an intense desire to communicate a vision of a transcendent order, a Promised Land of peace and harmony beyond our human preoccupations and disorder. In Alderton’s view, “he used Christianity as a discourse through which to critique and construct culture, and through which to join pacifism with nationalism” (31).

Alderton discusses McCahon in relation to other artists and artistic movements. She explores his inter-weaving of biblical themes and landscape. She discusses the importance of particular localities like Muriwai and Ahipara. She considers his interaction with Maori culture, on the one hand his admiration of Te Whiti and Parihaka, on the other the perceived affront of his Urewera Mural. She examines his beach walks engaging with death and the journey of the soul, his gates and waterfalls, his word paintings and his final warnings.

Alderton shows how McCahon’s last paintings have drawn a diverse response. Painted at a time of mental deterioration and drawing from the biblical preacher-philosopher Ecclesiastes, they have been interpreted not just as dark and brooding but as a sign that the artist ultimately lost his faith. Some have seen them as an expression of New Zealanders’ “addiction to the dark side” (302). Others think that McCahon ended his life doubting God’s existence and that his search for “paradise and pure Christianity” led to “ultimate disillusionment” (305). His daughter, Victoria Carr, said that finding his last work, I Considered All the Acts of Oppression, upside down on his studio floor, seemed like the closing of a book. But she warned that we cannot know what these final works mean because of his state of mind at the time (304).

In his lecture at the Question of Faith exhibition in 2003, Lloyd Geering interpreted McCahon’s Ecclesiastes paintings as confirming his own analysis of the movement of secular culture from theism to atheism and from certitude to doubt. Alderton quotes my dissent from such a view, or that the Ecclesiastes paintings demonstrate an ultimate loss of faith on McCahon’s part. They certainly reflect his increasing infirmity. The Paul to Hebrews series even has a spelling mistake and an inserted word. But other works from the same time period such as A Painting for Uncle Frank and Storm Warning are less bleak, and show that McCahon still had a “firm grip on faith’s paradoxes” (304).

Alderton herself sees the last works as a sign of McCahon’s despair at society’s rejection of his prophetic witness.

McCahon was indeed a Christian, albeit one who was dissociated with [sic] formal bodies of faith and strict theology…. McCahon seriously considered himself to be a prophet. These artworks represent the failure of his visual rhetoric, not merely his physical struggles as a result of illness. The Nationalist Project had come to an end by this era, and McCahon’s prophetic annunciations had fallen on deaf ears…. Because McCahon was a Christian as opposed to an atheist or lapsed believer, these final images are best read as reflections of the anguish caused by what he perceived as the overwhelming collapse of his prophetic ventures (305-7).

Testifying to a people “ever seeing, but never perceiving” (Isaiah 6:9), McCahon’s fate was that of an authentic biblical prophet.

Rob Yule is a retired Presbyterian minister, Bible teacher, lecturer and writer on theology and contemporary culture in Palmerston North

*To see the publishing details and ways the book is available please click on the image below

Gallery