How Church Can Appeal to Young People: A Critical Comparison

Many churches and church leaders are interested in how they can best format their services and overall environment so that they might appeal more to young people.

This interest has led to the emergence of various books and articles that seek to answer this question, both in order to retain those young people who have been raised in the church and also to attract young inquirers. This article will review some of the more prominent and recent of these works and identify five common themes that emerge across the literature. Many of these themes emerge from qualitative research projects in other contexts, or from the observations of pastors of churches that have successfully managed to attract and retain young people. Then, these themes will be compared to the findings from my own research, where I interviewed thirty-two recent converts to Christianity in Canterbury, New Zealand. Their experiences of church as young inquirers will serve as another source of data and will be used as a means of critically examining the claims made by ministry authors.

1. Support and Challenge

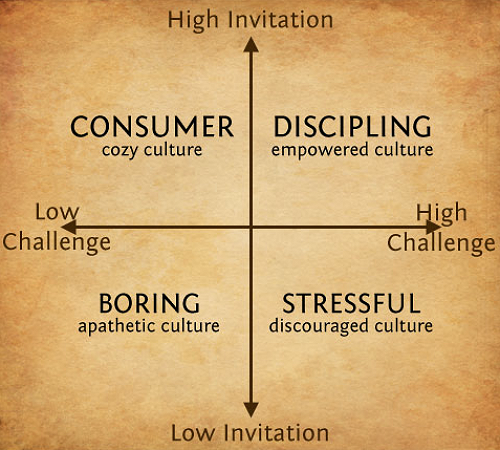

Pastors and researchers who write about Christian environments that retain and attract young people emphasize high levels of both “support” and “challenge.” These writers stress the value of an environment where young people feel cared for and supported, but at the same time are challenged and not simply allowed to remain as they are.[1] This principle is not one that is limited to the realm of church attendance in adolescence; parenting advice and Christian discipleship manuals, for example, are two other sources which occasionally use the same terminology. A good visual illustration of how these two factors can interact in a Christian context can be seen in the work of British theologian Mike Breen: (Please see Image One: Mike Breen’s Invitation/Challenge Matrix[2])

Although Breen is writing about discipleship, his diagram provides a useful visual aid as to the potential value of environments that are high in both support and challenge.[3] Breen uses the language of “invitation” rather than support, a slightly different concept, although it does contain notions of “vibrancy, safety, love, and encouragement” that are strongly supportive in nature.[4] In both cases, the argument is the same: people do well when they are a part of something in which they are both provoked and pastored, and such environments can also be quite attractive to outsiders.

In light of this, it comes as little surprise to find that specifically evangelistic events in and of themselves do not appear to have any significant correlation with increased adolescent attendance at particular churches.[5] Simply inviting a group of teenagers along to an annual youth camp may not result in much. However, if those young people are already well established in a network of supportive relationships at a local church, the camp can offer an important role insofar as it acts as an external “challenge” for young people to respond to.[6] It is important, therefore, that those running youth camps resist the urge to take their message too far down a therapeutic path in an attempt to minimise the unique strangeness of the Christian gospel and remove any challenge or provocative truth.[7]

2. An Understandable Message

The second factor that has emerged across the literature as being valuable in helping young people join and remain a part of local congregations is their engagement with the message of the church.[8] Of course, every preacher believes that their message is perfectly understandable, but not every preacher can testify to a church full of young people eager to hear every word! Careful and sensitive contextualisation is required, and one compelling biblical example of this can be found in Acts 17, where the apostle Paul preaches to a group of educated Athenians. Summarising the content of Paul’s speech, John Finney notes:

[Paul] does not begin with any biblical text, but dwells on a particular New Age symbol. He not only quotes various New Age gurus, but agrees with them. He does not quote the Bible, he does not use the name of Jesus, and he gives no account of the cross and the atonement. He adopts a sort of universalistic stance … At the end of this feeble effort he asks them to respond. Rather surprisingly some do.[9]

Luke notes that this message resulted in some conversions, including from within the local social elite. While responses across the group were mixed, and certainly not unilaterally positive, New Testament scholar Craig S. Keener suggests that Paul’s communication here is still very effective because it succinctly broaches the topic of resurrection to an audience that finds the notion preposterous. Keener points out: “That Paul has even a few converts from the Areopagus and its circle of hearers (17:34) appears remarkable. Even critics now understand resurrection.”[10] Paul communicates foreign (even distasteful) ideas in familiar language and prose, the evidence of his success displayed in the clear response of his hearers.[11] However, how many modern theologians would take issue with Paul’s preaching in this context, decrying its apparent lack of Christology, among other things? To Paul’s credit, he at no point compromises or edits Christian theology in this speech. Rather, he picks facets of that theology which he knows will make sense to his hearers and relates them as best he can to their current circumstances and understanding. It is this kind of communication that appears to be best suited to ensuring and encouraging young people’s participation in local churches today.[12]

3. Connection and Relationships

The third factor which is significantly associated with young people’s affiliation with a local church is the presence of multiple, warm friendships with people at the church. Again, here is a factor that is not exclusive to churches. People often leave or join religious groups based on the presence or absence of meaningful friendships in those groups.[13] These affiliations are strengthened if connections occur with more than one person and occur reasonably early on in an individual’s engagement with the group.[14] While one cannot simply make congregants friendlier, some writers, such as American megachurch pastor Andy Stanley, discuss how they create spaces in their church programs where friendships would more naturally occur, as people were put alongside one another in shared interest groups or at community meals.[15] Stanley sees such initiatives as directly contributing to the growth of his congregation.

Also, for many, their relationship with a pastor or pastors influences their attendance. In larger churches, where senior pastors may delegate some of their immediate leadership tasks to volunteers or a pastoral team, a positive relationship needs to occur with someone in leadership, rather than specifically the person at the top with the title.[16] In smaller churches, the pastor’s connection with newcomers has been shown to be a significant factor in how churches welcome and incorporate visitors.[17] For young people, while they do not necessarily need their pastor to be cool or hyper-attuned to their various tastes and trends, they are more likely to stick around if they perceive the pastor of their church as being empathetic and trusting of them.[18] Pastors who invite young people to share responsibility and who are willing to delegate meaningful tasks and roles to young people in their congregations, often reap the rewards of such trust by earning the continuing respect and loyalty of those young people.

4. A Comfortable Space

The impact of the local church’s physical layout, comfort level, and organisation on the faith journeys of inquirers is another point raised by ministry writers. This can involve a wide variety of practical factors such as the use of multimedia technology, the tidiness of various spaces, and the quality of the music.[19] However, a unique tension arises here. For while the pastors of churches that have been successful in attracting and retaining young inquirers will happily emphasise the value of such structural factors, the same emphasis is largely absent from studies that seek to interview recent converts to Christianity in the West. For example, Scot McKnight, in Turning to Jesus: The Sociology of Conversion in the Gospels, directly cites nineteen different students’ conversion narratives, and church environments are barely mentioned.[20] Likewise, Growing Young, a project that interviewed clergy, young people, and families involved with churches that had a growing cohort of young people, paid little attention to such things, and almost seemed to stand in opposition to such claims at times.[21]

There are two possible explanations for this difference. The first is that the reason converts and inquirers do not mention features such as good quality music, multimedia, and layout may well be because they do not notice the positive effect these are having on their continued attendance. Perhaps it is only when something is done badly or not at all that a newcomer pays attention to it.[22] Pastors, on the other hand, certainly do notice these aspects of the church service and the positive effects they are having. This is largely because they were often the people responsible for instilling these changes in the first place and may be predisposed to overestimation in their assessments as they look for evidence that their work was justified. The second possible explanation is that factors such as music, layout, and presentation do not matter that much as attracting features. The explanations given by these pastors may be simply a result of the size of their churches. It is hard to know for sure exactly which of these explanations is the truest, although the former does seem to make the most sense whilst still dignifying these pastors’ descriptions of what they have observed over time.

5. Acts of Local Service

The final characteristic noted in research on ministry is also one that requires some nuance. It has been observed in some settings that what are often called “community ministries” do not have much of a direct correlation to local church growth.[23] However, churches that do have a regular and growing cohort of young people are often heavily involved in their local communities, and this feature is one that is commented on positively by the young people themselves.[24] This leads to a couple of conclusions. The first is that community ministries on their own do not appear to be enough to attract young people to churches. Nevertheless, it may be that alongside some of the other factors already mentioned, the fact that a church is involved in charitable action in its immediate neighbourhood is appealing. The second conclusion is that community-focused churches can earn the respect of inquirers, which can be a helpful starting point that leads on to further engagement with other aspects of the church. American youth ministry theologian Kara Powell and her colleagues recount in detail the story of a young woman, Alexis, and her journey into a local church following a shift to Washington D.C. Early on in her time in Washington, Alexis stumbled across a local festival where community organisations were each “offering opportunities to make a difference.”[25] Intrigued by a group whose stated aim was to home hundreds of currently displaced foster children in the city, Alexis signed up to indicate her commitment and engaged the organisation’s volunteers in conversation. She soon found out “that these volunteers weren’t just part of a non-profit organization — they were part of a church … The more Alexis asked about the activities and overall spirit of the church, the more she felt like this was a church she could imagine joining.” Eventually Alexis did join this church, and a year later was heavily involved in its activities.[26] Significant for Alexis was the fact that the church had aims other than trying to lure her into attending a service at their building. They were also interested in contributing to the wellbeing of displaced foster children in the city, a cause that appealed to Alexis and prompted her to inquire further.

The Findings from my Interviews

Careful readers will have noticed that much of what has been cited above has come out of a North American context. This is mostly due to the large number of published works on church growth that come from that part of the world. The context of my own research was not North America, but Christchurch. I interviewed thirty-two young adults who had converted to Christianity in their teens, whilst coming from families in which neither parent was a practising Christian. Thirty of my participants had come to faith in the Canterbury region; two others were living on the West Coast of the South Island at the time of their conversion. I was interested to compare the comments of my interviewees with the claims made by influential church growth authors. Given that New Zealand is also a Western nation, I assumed that some themes would emerge in the interviews, but also that the difference in context would at various points create a difference in how church was experienced and perceived. In the second half of this paper, I outline how and where these similarities and differences emerge.

Relational Warmth and Friendships Matter

My findings support the claim made by Powell, Mulder, and Griffin that “Warm is the New Cool.”[27] In their discussion of young people’s religious attendance, these authors set relational warmth as a key factor over and against such other commonly assumed helping factors, such as a precise size, a trendy pastor or message, and a ministry program that is always hyper-entertaining.[28] Similarly, my participants talked at length about the people who cared for them, the sense of community they found at church, and the friends and leaders who demonstrated consistency and care as they embarked on a journey of faith. Some did express appreciation for various activities and forms of worship within their churches such as the style of the music, or the games and activities at youth group that helped them build connections while they were still newcomers. Yet these things would have been deemed inadequate were it not for the strong relationships with friends and leaders that were also occurring.

I mentioned earlier that Christian ministry authors often argue that inquirers need to feel a sense of both support and challenge as they engage with church and faith. One major support factor for my participants was the presence of a friend or friends, who accompanied the young person as he or she engaged with church and faith for the first time. These friends were often the same age and gender, and while many were Christians, it is important to reiterate the fact that their primary role was not as “friendship evangelists,” where the relationship exists only as a tool to attempt to affect change in another person,[29] but rather as trusted companions on the journey of faith. Twenty-three participants mentioned individual friends that they saw as playing key roles in their conversion journeys. These friends gave participants someone to attend church or youth group with, to sit alongside, to participate in activities with, and sometimes to discuss the content covered with afterwards. Almost all of my participants mentioned friends, and groups of friends, at some point in their conversion narratives, and attended churches where there was some cohort of people their own age. Only two participants appeared to buck this trend.

On a basic level, this finding mirrors much of the existing literature that points to relationships and friendships as key in determining the level and duration of an individual’s engagement with a faith community. Yet also, on a theological level, my observation here provides some support for arguments made by both Andrew Root, and Powell, Mulder, and Griffin. These writers are fundamentally opposed to the notion that relationships exist as a tool or an end towards some other outcome. This, they argue, is a now defunct ministry strategy that is inappropriate both theologically and culturally.[30] A better approach is to see friends as able to provide presence, empathy, and companionship, and to see these values as ends in and of themselves. While some of my participants did describe theological conversations that they had with these friends, these were usually facets of a much broader relationship, rather than the primary reason for the friendship’s existence.

Valued relationships with pastors and other leaders at church was another common factor described by my participants. Leaders who were identified as being particularly significant were described as admirable, relatable, and available. While it is in some ways outside of any individual’s control exactly what a young person might see in them as admirable or relatable, certain qualities seem more likely to elicit the respect and admiration of others, and particularly of young people on a journey of faith. My participants admired their leaders for being caring, inclusive, energetic, forgiving, consistent, and informative. They also felt encouraged at points where they saw their leader as someone they could relate to and who could relate to them and their world. These are not traits that can simply be engineered or manufactured. Other literature confirms the important role a pastor or leader plays in a young person’s faith development, and even the fact that this often has a lot to do with their empathy and openness to young people.[31] However, the theme of admiration, which is not always mentioned,[32] is a strong theme that emerges within my data set, and a useful point within youth ministry theory. The fact this admiration has so little to do with what can be managed and programmed, and so much to do with the inner life and virtues of Christian leaders, makes it all the more challenging and vital.

Christian Community feels more Counter-Cultural than Christian Preaching

Some ministry authors have suggested that the preaching of the church also has the potential to be a significant counter-cultural experience for new attendees.[33] However, if this were true for my participants, it was not something that was made abundantly clear in the interviews. Some struggled to comprehend, or actively chose not to listen to, the preaching at their churches. One participant, Martin, recalls “struggling to listen, struggling to get something out ... what the preacher was saying … It was kind of like I had to learn how to do church.” It took Martin some time before he was able to fully comprehend and feel edified by the preaching at church, as he felt as though he needed to “learn how” to engage with sermons.

However, right from his first few visits to this church, Martin did perceive a clear contrast between the relational interaction within the congregation and that which he was used to at school: “[Church contained some] genuinely nice people, and it was such a contrast from school as well, where you're like, just waiting for someone to mock you about something. But … at church, you'd never get a word like that at all, and it was just refreshing.” Other participants did mention stories, theology, or practical teaching as things they appreciated as part of preaching but made no obvious contrast between these and the messages of secular New Zealand society. In some cases, it was more an experience of consonance than dissonance, as participants realised how their values and aspirations matched the themes being discussed by their preachers. This too has some support from a couple of authors who are finding some success in preaching to youth and young adults today.[34]

Certainly, the preaching of the church was an important factor in the conversion journeys of some of my participants. However, the primary observation from my findings about the perception of the church as counter-cultural is not so much about preaching, but Christian community. This is the major point at which many of my participants realised that they were in a space where things were quantifiably different from those of the world they usually inhabited. Some participants, such as Martin, spoke about how they found the church to be a refreshing contrast from the sort of social environment they were experiencing at school or at home. This was most commonly due to a direct comparison being made between the behaviour they observed between Christians at church and that which they had observed elsewhere. Environments like Easter Camp, with its size and duration, allowed this to be experienced at a greater intensity. Christian community was perceived as something counter-cultural, both in its fellowship and in some of its practices. This observation reorients Christian ministry somewhat, away from the more achievable quantities such as a few tweaks to the preacher’s sermon style (although that is not a bad thing) towards a deeper quality of a Christian community that both feels and is different from any other community in contemporary society — and this because of Jesus and his work within that community. Here is the point at which unchurched young people are likely to sense that they are in a different space.

Little Mention of Acts of Local Service

One interesting characteristic of my participants’ descriptions of church and what mattered to them is the lack of much talk about these churches’ community and social action. In at least some of the literature that discusses the association between such socially conscious churches and increased religious attendance amongst the young, the data gathering methods are much broader than my own and are not simply restricted to participant interviews.[35] However, other writers make the point that while community action does make some sort of difference, it is hard to tie it directly to conversion decisions.[36] This is likely the case within my sample; many of the churches that referred participants to me were heavily involved in their local communities, and most had youth workers present in local high schools for ten hours a week under the 24-7 Youth Work model. I was particularly interested in examining the impact of this upon conversion, following on from my own previously conducted research and my experience as a 24-7 Youth Worker.[37] However my participants spoke little about the mere fact of having youth workers in their high schools as important. Where these youth workers were described, it was more about their personal traits and care for participants, both in school and at church. Participants were not obviously impressed by the fact that a church was paying a young adult to visit the school for ten hours a week, but they certainly did take note when that individual demonstrated care, empathy, and consistent support. Often, they observed these things occurring outside of school anyway, in environments such as a church or a camp setting. What mattered to my participants most was not that there was a youth worker in their school, but that there was someone in their life who was caring, loving, and admirable.[38] The fact that this person was at school may well have made that connection easier, but if so, this was not something my participants were particularly aware of or saw the need to comment on.

Conclusion

My findings fit, at least in part, with three of the points raised in the first section of this paper. A church that is relationally warm and is high in both support and challenge (even if that challenge comes through means other than a preached message) is best poised to attract and retain young inquirers. Also, a church’s involvement in its local community, as expected, will not necessarily be perceived as directly influencing an individual’s faith decision, but will nonetheless be of benefit to that church in its mission towards nonbelievers. At the very least it exposes secular people to caring Christians. However, I heard little to nothing from my participants about how comfortable their church spaces were. Worse still, some of my participants told me that they used to actively ignore or simply fail to understand the preaching at youth group and church. So much for carefully crafted, contextualised messages in helping people come to faith! My participants were not moved by such means, but they certainly did sit up and notice when they observed both communities and individuals showing genuine care towards one another and towards the strangers in their midst.

David Bosma is a PhD Student with the University of Otago, and his research focuses on experiences of conversion during adolescence among young people from secular families. David is also personally involved in youth ministry as a volunteer youth leader at his local church, a 24-7 youth worker, and has had previous experience as a full-time youth pastor at a Baptist church in the Canterbury region.

[1] Gay L. Holcolmb and Arthur J. Nonneman, “Faithful Change: Exploring and Assessing Faith Development in Christian Liberal Arts Graduates,” New Directions for Institutional Research 122 (Summer, 2004): 93-102; Andy Stanley, Deep and Wide: Creating Churches Unchurched People Love to Attend (Grand Rapids, Zondervan, 2012), 76; Kara Eckmann Powell, Jake Mulder, and Brad Griffin, Growing Young: Six Essential Strategies to Help Young People Discover and Love Your Church (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2016), 126-162, 211-212; James Emery White, The Rise of the Nones: Understanding and Reaching the Religiously Unaffiliated (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2014), 123.

[2] Chart sourced from Will Mancini’s Blog Post, “#5 on the 2014 Ministry Vision and Planning Countdown: Mike Breen’s Invitation and Challenge Matrix”: https://www.willmancini.com/blog/5-on-the-2014-ministry-vision-and-planning-countdown-mike-breens-invitation-challenge-matrix.

[3] Breen develops this schema in his book Building a Discipling Culture: How to Release a Missional Movement by Discipling People Like Jesus Did (Pawleys Island: 3 Dimension Ministries, 2009), 18. There he describes how he is building this concept out of his reading of the gospels, arguing that “Jesus created a highly supportive but highly challenging culture.”

[4] Ibid., 14.

[5] Thom Rainer, Effective Evangelistic Churches: Successful Churches Reveal What Works and What Doesn’t (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1996), 29-48;

John Finney, Emerging Evangelism (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 2004), 123.

[6] A good discussion of the effectiveness of youth camps in evangelising young people can be found in Thomas E. Bergler and Dave Rahn, “Results of a Collaborative Research Project in Gathering Evangelism Stories,” Journal of Youth Ministry, 4:2 (Spring, 2006): 65-74.

[7] For a somewhat cynical take on the effects of this kind of preaching at youth camps, see Shane Claiborne, The Irresistible Revolution: Living as an Ordinary Radical (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006),37-38.

[8] See, for example, Scot McKnight, “The Gospel for iGens,” Leadership 30:3 (Summer, 2009), 23; Timothy J. Keller, Center Church: Doing Balanced, Gospel-Centered Ministry in Your City (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2012), 307-308, and Stanley, Deep and Wide, 80, 229-241.

[9] Finney, Emerging Evangelism, 92.

[10] Craig S. Keener, Acts: An Exegetical Commentary, Vol. 3, (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2014), 2675.

[11] Even those who sneered clearly understood Paul enough to find his ideas preposterous. See Acts 17:32.

[12] Powell et al., Growing Young, 143 note that in their research, young people appreciated hearing messages about how the teaching and ministry of Jesus affected their lives here and now, particularly as it pertained to issues of social justice. These young people were also not put off if they perceived such messages to be challenging them to change.

[13] For example, American sociologists David Snow and Cynthia Phillips discovered a similar dynamic present in converts to Nichiren Shoshu, a form of Japanese Buddhism. See David A. Snow and Cynthia L. Phillips, “The Lofland-Stark Conversion Model: A Critical Reassessment” Social Problems 27:4 (April, 1980): 440.

[14] Finney, Emerging Evangelism, 136; Roy M. Oswald and Speed B. Leas, The Inviting Church: A Study of New Member Assimilation (New York: The Alban Institute, 1987), 58.

[15] Stanley, Deep and Wide, 133-134.

[16] Oswald and Leas, The Inviting Church, 35.

[17] Rainer, Effective Evangelistic Churches, 85-86.

[18] Powell et al., Growing Young, 50-92.

[19] See, for example, Stanley, Deep and Wide, 157-182.

[20] Scot McKnight, Turning to Jesus: The Sociology of Conversion in the Gospels (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002).

[21] Powell et. al., Growing Young, 25-27.

[22] Brian McLaren makes this point, in More Ready Than You Realize: Evangelism as Dance in the Postmodern Matrix (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2002), 88.

[23] This is made most apparent in Rainer, Effective Evangelistic Churches, 136, 146, although there is also some suggestion of this idea in Oswald and Leas, The Inviting Church, 15-17, 39, 57-58, where congregational factors such as friendliness and unity are shown to have a much greater effect on church growth than community action, although it is seen as a helping factor in a minority sense.

[24] Powell et. al., Growing Young, 248-250.

[25] Ibid., 234.

[26] Ibid., 234-236.

[27] Powell et al., Growing Young, 163. Their chapter is entitled “Relational Warmth is the New Cool.” (pp. 163-195).

[28] Ibid., 25-26.

[29] E.g. as described in Andrew Root, The Relational Pastor (Downers Grove: Intervarsity Press, 2013), 41.

[30] For the argument as to this strategy’s theological weaknesses, see Andrew Root, Revisiting Relational Youth Ministry: From a Strategy of Influence to a Theology of Incarnation (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2007); for an argument as to why this does not fit culturally, see Powell et al., Growing Young, 145.

[31] Powell et. al., Growing Young, 50-88.

[32] Although Tim Keller does briefly mention it. See Center Church, 64.

[33] Ibid., 307-308, and also Stanley, Deep and Wide, 80, 222, 229-230.

[34] Scot McKnight, “The Gospel for iGens,” Leadership 30:3 (Summer, 2009), 20-25; also Keller, Center Church, 303-304. These authors would argue that this sense of consonance is helpful in that it attracts young adults to their services and gives them a greater opportunity to engage with the messages.

[35] E.g. in Powell et al., Growing Young, 242. The authors did note some response from the young people who took part in their research in this area, but a greater response came from the pastors they interviewed.

[36] Emery White, The Rise of the Nones, 100, 143; Rainer, Effective Evangelistic Churches, 136, 146; Oswald and Leas, The Inviting Church, 15-17, 39, 57-58.

[37] David Bosma, “The Role of the 24/7 Youth Worker in the Pre-Conversion Faith Formation of Young People in High Schools,” Honours Dissertation, University of Otago, 2016.

[38] Admiration is something Timothy Keller mentions as of value in convincing sceptical inquirers about the value of faith. See Center Church, 284.

Gallery