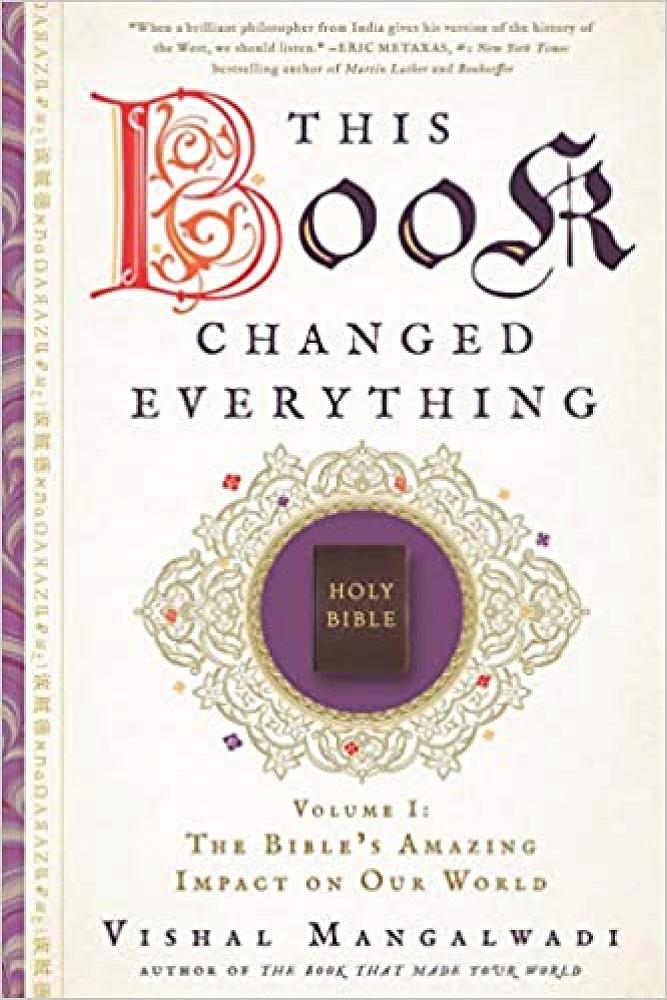

Book Review: This Book Changed Everything. Volume I: The Bible's Amazing Impact on our World

Vishal Mangalwadi, Pasadena: Soughtaftermedia, 2019. XXII + 316 PP. ISBN 9788186701249. US$24.95.

This is an intriguing and unusual book. But I found it also frustrating. The style is somewhat meandering and inclined to follow what appears to this reader to be digressions. It is as if a certain line of thought prompts a tangential idea. There are anecdotes aplenty; and some personal reminiscences. This is a book of ideas and assertions that overall lacks an organising principle.

The theme of the book, as the subtitle suggests, is the influence of the Bible on Western thought and its technological and scientific development. It might be better to say that it is the influence of those whose reading and understanding of the Bible determined, at least in part, their beliefs and actions. For instance, Katherine von Bora learned the skills of household husbandry and economy within the cloistered world of her nunnery. She took these into her marriage to Martin Luther to become an enterprising businesswoman and landowner, thus making her the “mother of the modern economy of the people, by the people, and for the people” (201). Martin Luther’s own “Larger Catechism” instilled into the German people a good work ethic. Zwingli, in Switzerland, established a theologically-based schooling system that turned young men from mercenaries fighting foreign wars into industrial leaders and innovators.

Another theme of the book is how the West has moved away from the truth of Scripture, and revelation, to a “post-truth” intellectual decline towards nihilism and a Buddhism-inspired sense that the self is an illusion. Revelation is an important source of knowledge, but this need not be Christian revelation, it seems. Mangalwadi uses the story of the Indian mathematical genius, Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887–1920), who received ideas in dreams (attributed to his god, “Namagiri”), to show that consciousness is not simply a product of “non-rational chemistry” (40). This is linked to a larger point that both Paul’s and Peter’s understanding of human freedom came through revelation, including visions (see, e.g., Acts 10:9–16).

A chapter entitled “Bloodshed for Tolerance,” which traces the rise of tolerance in Europe, especially through the writings of Tertullian, Lactantius, and the post-Reformation arguments of Johannes Althusius, provides a consistent and more coherent demonstration of the influence of the Bible on the development of tolerance. Nonetheless, even here, as elsewhere, there is a tendency on occasion to resort to proof-texting.

In broad terms, one can accept how concepts, ideals, and truths derived from the Bible, and mediated through various philosophical and religious writings and teachings have laid the ground-work for many of the West’s institutions and ideas, e.g., the rule of law, democracy as the sovereign will of the people, government officials as “servants” of the people. It will help if one shares Mangalwadi’s basic presuppositions. But a sceptic, or someone looking for a well-developed thesis, will not likely be convinced. There are too many generalisations, too many instances of selective examples and illustrations, and arguments set in too narrow a conspectus.

At one point, for instance, Mangalwadi raises the question of why the US did not become an empire. It was, it seems, because the founding fathers “saw empire through God’s perspective, as tyranny” (135). They understood “[t[he rulers’ job was ‘to secure’ the rights of ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ that the Creator had given every human being” (136). Moreover, the understanding that empire is bad, while the sovereign nation-state is good, may be established from the Bible: God has set the boundaries for the nations, see Acts 17:26, 27; Deut. 32:8.

Mangalwadi does not consider whether US economic power is a form of imperialism; nor whether the US’s interference in the national sovereignty of countries in South America (and elsewhere) is a form of imperialism. Nor does he ask why Britain, a nation founded on Christian principles, should have become an empire. He flattens out historical processes and sheets home political ideas such as “every nation’s right to self-determination” to biblical passages by isolating certain historical influences and ignoring others; not to mention ignoring the Bible’s own ambiguities over kingship, empire (e.g., King David’s realm?) or nation-states.

At the outset of a chapter entitled “How Did ‘We the People’ Become Sovereign?”, Mangalwadi states that when India gained independence from Britain, all the various states, some ruled by Hindu rulers, others Muslim, other directly by the British, became independent: “Sovereignty, however, did not revert to the princes. For the first time in Indian history, citizens became sovereign, even if they did not know what that meant” (167). My immediate reaction was to ask: “What about Kashmir?” Here, of course, a Hindu ruler decided to join the nation of India, against the wishes of his (majority) Muslim subjects.

Nevertheless, though this book may prompt many questions and offer up not a few non-sequiturs, it also contains interesting insights into aspects of the Bible’s influence, direct or otherwise, upon Western values and political institutions. It was interesting to learn that Lincoln’s phrase in his Gettysburg address, “of the people, by the people, and for the people,” derived from the prologue to Wycliffe’s Bible (170). Though it shows that the Bible’s influence is sometimes mediated through adjuncts to the Bible, Mangalwadi relays that a sermon by Jonathan Mayhew, described by later historians as “the first volley of the American revolution,” which outlined “the biblical basis for submission to authority and rebellion against tyrants,” was drawn from “anti-tyranny notes” in the Geneva Bible. A reason, states Mangalwadi, why James I demanded that the King James Version “should have no marginal notes at all” (143).

Two chapters were submitted by associates. One by Ashish Alexander on “The Bible and Origins of Modern Indian Fiction” looks at the development of the Indian novel, as influenced both by early English fiction, e.g., Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress and the availability of Bible translations whose prose “breathed new life into prose in various Indian languages” (235) and found in the comparative characters of Mary and Martha inspiration (through such characters in English fiction) for a number of female characters in Indian novels.

The other, by journalist Jenny Taylor, entitled “From Prophetic Press to Fake News,” traces the indications of the “biblical roots” of the free press through the influence of “passionate Christian” William Thomas Stead, the fact that nineteen of the twenty top countries listed on the World Press Freedom Index are “nations whose constitutions grew out of the Reformation struggle for freedom” (254), and the effect of the missionary press in nineteenth-century China. The chapter concludes by looking at the death of news through the “balancing of subjectivities” (where “balance” trumps objectivity). But there are still those ready to “take up their cross for truth and public good” (268), and such sacrifices will have to continue to rescue news from its “current morass.”

Derek Tovey is the book review editor for Stimulus.