Reading Philippians in a Pandemic

In recent weeks, I have been reading through Paul’s letter to the Philippians. It is interesting how our current context, living as we are through a global pandemic of COVID-19 and its effects, influences and affects the way that this text speaks.

We hear, and use such words and phrases as “social isolation,” “physical distancing,” “lockdown,” “we’re all in this together,” “staying connected,” “be kind to each other,” “keep to the rules,” and so forth. In this article, I explore how we might apply some of these concepts to a reading of Philippians, and how the letter may shed light on our experience of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Social isolation, Physical Distancing, Lockdown.

Paul writes this letter from prison. He’s in a form of social isolation, if you will: certainly, “lockdown.” Paul’s imprisonment may have allowed a certain amount of contact with those friends who were with him in the city where he was imprisoned. Several times Paul speaks of being “in chains” (Phil 1:7, 13, 14, 17),[1] though this may simply be a way of referring to his being in prison.[2]

Nevertheless, Paul is imprisoned at some distance from the Philippians, and unable to visit them as he would wish. It is not certain where exactly he was imprisoned: scholars suggest Rome, Caesarea, or Ephesus.[3] Both Rome and Caesarea are a long way away; and, while Ephesus is much closer, it is still a good distance. Paul cannot visit anyway, and his only recourse is to send fellow Christians, Timothy and Epaphroditus (Phil 2:19–31), and, in the case of Epaphroditus, probably with this letter.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, we are blessed to have modern technology, telephones, smartphones, computers, apps, and platforms (Skype, Zoom, Jitsi) to enable us to keep in touch, and even to have “face-time.” Paul’s means of keeping in touch was by personal visits, or visits by others, and by letter. As Morna Hooker says, travel was “arduous and slow.”[4] However, Roman roads were good, sea travel had been made safer from threats of piracy (though storms and bad weather could seriously disrupt travel and make it unsafe) so communications at the time were relatively good.[5]

Despite the restrictions on Paul, he assures his readers that there is a ’silver lining’ to his imprisonment. Indeed, Paul sees it as more than an upside to a bad situation; in fact, his imprisonment has actually helped the spread of the gospel. The reason for his imprisonment has become known throughout “the imperial guard” and, indeed, many of his fellow Christians have themselves been emboldened to witness and themselves proclaim the gospel (1:12–14).[6]

During the pandemic, clergy and others have looked for new and different ways to offer services, and to provide spiritual resources to people in lockdown. There have been some imaginative and creative offerings. The gospel has been presented through the medium of social and other media, and who knows whom these messages may have been reaching? I heard an Anglican Māori cleric talking to a reporter on Māori TV about the type of response he noticed to what he and others were offering online. He expressed surprise at the fact that so many were tuning in, not only far more than expected, but far more than would be usual in times past. Certainly, there are many possibilities for someone who is not generally a churchgoer, or who knows little of the Christian faith, to stumble across a service, or some Christian input on the internet. Who knows what affect such exposure may have?

We’re All In This Together

One of the aspects of Paul’s letter to the Philippians that shines through strongly is the strong bond of love and fellowship that exists between Paul and the Philippian believers. Paul begins his letter with a long thanksgiving to God for the way the Philippians have shared with him in the gospel (1:5). The word Paul uses here, koinōnia (sometimes translated “fellowship”) is a rich, and important term in this letter. “Fellowship” is, perhaps, too weak a word: or it has been devalued in our modern usage. The Philippians’ koinōnia with Paul has involved a partnership with him, which has involved financial support (see Phil. 4:10–18), and other material help. This koinōnia may have included the sharing of human resources, personnel from the congregation who have worked alongside Paul in his missionary endeavours, and have been there to assist him.[7] Epaphroditus is one such person; and there have, no doubt, been others (Euodia, Syntyche, Clement, and Paul’s “loyal companion”; Phil 4:2, 3; NRSV).[8]

Not only do the Philippians partner with Paul in his mission and ministry, but they also suffer with him. In Philippians 1:29 and 30, Paul writes:

For [God] has graciously granted you the privilege not only of believing in Christ, but of suffering for him as well–since you are having the same struggle that you saw I had and now hear that I still have.

What the “same struggle” that Paul and the Philippians share in is not entirely clear. Most probably they both experience persecution for the cause of Christ. And are some of the Philippians believers, at least, facing imprisonment for their faith? The word that is used for “struggle” is an athletic image, and later, Paul will speak of pressing on to reach the “goal” and the “prize” of the “heavenly call of God in Christ” (Phil 3:12–14). Another way of reading v. 12 is to understand Paul as saying that he does not consider himself yet to be “made perfect.” So perhaps the “same struggle” that the Philippians share with Paul is the continued call to strive towards greater completion is Christ, toward more faithful discipleship. Whatever the case, this letter shows Paul and the Philippians being “all in it together” in their Christian walk and experience.

In the midst of a COVID-19 lockdown, which we are “all in together,” it may at times be difficult to put into practical effect the sharing and concern for others that we might wish, confined as we are to our homes and our localities. Some reading this will have, no doubt, experienced the pain of separation and distance from those they love and are concerned about, as they are not able to visit or help them as they have previously been accustomed to do. We do our best, by phone call and internet, to offer support and care. We are all in this together both in the shared experience of restriction and disruption to ‘normal life’: but in a sense, we are also in this together in our differing circumstances and different experiences. It is why we are called to kindness, and to thoughtfulness of the situations in which others find themselves.

Staying Connected

As mentioned above, Paul’s main method of staying connected with the Philippian church, a church he seems to have had especially warm relations with, was by personal visits and by letter. Paul has every hope that he himself might soon be able to make a visit (Phil 1:24–26; 2:24), but in the meantime, he plans to send Timothy (2:19, 23). He knows that Timothy is someone who is concerned for the welfare of the Philippians, and Paul expects him to bring back news of the Philippians that will encourage Paul (Phil 2:19–20). However, it seems that Paul also needs Timothy with him to help him (Timothy is like a son to him), and he does not think he can spare Timothy until he is more certain of what his own future prospects are (Phil 2:23).

So Paul intends to send Epaphroditus on ahead, even before he despatches Timothy. Epaphroditus is most probably to carry the letter that Paul is now penning. It would seem that Epaphroditus is a member of the Philippian Christian community, and he has previously been sent by the church to help minister to Paul’s need (2:25). He is described by Paul as a “brother, co-worker, and fellow soldier,” so he is obviously someone who is valued by Paul for his support and collegial work in the mission.

But Epaphroditus has been very ill, and indeed his illness was very nearly terminal: but, says Paul, “God had mercy on him” and he has recovered (Phil 2:27). The Philippians have heard that Epaphroditus was ill, and their concern has made Epaphroditus distressed. The close bond between him and his fellow Philippian believers is evident: the fact that they are worried about him has affected him deeply (he no doubt wishes to be able to reassure them in person), and anyway, he is missing them greatly (Phil 2:26). Epaphroditus’ distress has added to Paul’s anxiety, for Paul also wishes to be encouraged by knowing that the Philippians are encouraged to find Epaphroditus in good heart (2:28). Paul also believes that Epaphroditus’ recovery from a serious illness was God’s mercy to him, Paul, as well, so that he would not have the sorrow of losing a good colleague and friend on top of all his other troubles.

All this demonstrates the close bonds of affection and relationship that exists between Paul and Epaphroditus, and between Epaphroditus and the Philippian believers back in Philippi. Out of these bonds they work to keep connected with one another, first by the Philippians sending Epaphroditus to be with Paul, and then Paul releasing Epaphroditus back to them, carrying with him a letter to encourage and build up the Philippians in their faith.

One of the important benefits of the lockdown may be the way in which we have made extra efforts to stay connected with one another. While there have been complaints about the energy-draining effects of Zoom meetings, the internet, the smartphone, and the telephone have been a real boon in helping keep people connected. But, beyond that, we have been making an extra effort to stay in contact with our significant others. We may even have been contacting people whom we do not usually connect with very often, if at all. We have, no doubt, enjoyed catching up with folk using an internet social platform of some sort. My own church has used a platform called Jitsi, and after the service has ended, groups of people have stayed online to chat amongst themselves. The housegroups have been encouraged to fellowship together as a group after the online services. As I write this, I’ve received an email from our vicar stating that the church leadership is working on setting up more groups so that all members of the church can be connected with others in some way. Hopefully, bonds may be strengthened between people that will continue on beyond the current crisis.

Look After One Another’s Interests and “Be Kind to One Another.”

As Paul gets ready to send Epaphroditus off with his letter, he writes:

Welcome him then in the Lord with all joy, and honour such people, because he came close to death for the work of Christ, risking his life to make up for those services that you could not give me (Phil 2:29, 30).

Paul writes about how Epaphroditus has been “risking his life.” We, too, have seen instances of people risking their lives to help others. We think of the doctors, nurses, paramedics, ambulance drivers, and other medical personnel who have worked tirelessly to nurse the ill, and to tend to the dying. Many of them have “risked their lives” in order to offer help and attention to those in dire need. Sadly, especially in very badly affected parts of the world, such as in Italy or in New York City, many have died as a result of their work with persons infected with the Coronavirus. Around the globe, people have rightly had, sometimes nightly, rituals where they have applauded health workers from their front doorsteps, balconies and windows.

But it has not just been health workers who have felt exposed and vulnerable in carrying out their duties. Police, residential, and home care workers, shop and supermarket workers, and others have expressed their sense of vulnerability, and sometimes their fear of being exposed to the virus as they work on “the front line.” In the face of this, however, there have been those who have expressed their determination to keep on offering their services. As one woman I heard one evening on TV One news expressed it, her love of people overcame her fear of the virus. It has been appropriate and heartening that members of the public have also expressed their appreciation of what these “front line workers” have been doing. Some will have been doing things on our behalf, things we would do ourselves if we were free to. I think of the Student Volunteer Army delivering groceries and other shopping to those confined to their homes and unable to get out.

As Christians, Paul reminds the Philippian believers (and, through his enduring letter, us as well), that we are called to look after one another’s interests, and not simply our own (Phil 2:4). He goes on to provide us with the example of Christ, very probably drawing upon the words of an early Christian hymn (Phil 2:6–11),[9] who did not “grasp at” equality with God, and who did not use his position as God to his own advantage. Rather, Christ became a humble human being, indeed, he took the form of a slave, and lived a life of service and of obedience to God that took him on a path towards death on a cross.

The example of Christ sets the bar extremely high. We are then called to a “kindness” which far outstrips polite interest and casual concern for another’s situation. We are called to a self-giving, self-sacrificial interest in the affairs of others that far outstrips our natural inclinations, or our human capacity. No wonder Paul exhorts his readers to “let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus” (2:5), tells the Philippians to welcome Epaphroditus “in the Lord” (2:29), and so often speaks of doing things “in Christ,” or “in the Lord.” Paul knows that it is only by the power of God, through the Holy Spirit, that we can attain to the level of kindness and caring for others’ interests that he outlines here.

“Work out your own salvation,” and Keeping the Rules.

After Paul has exhorted his Philippian readers to be concerned for the interests of others, and has quoted the early Christian hymn to provide a template, as it were, for our approach to doing this, he goes on:

Therefore, my beloved, just as you have always obeyed me, not only in my presence, but much more now in my absense, work out your own salvation with fear and trembling, for it is God who is at work in you, enabling you both to will and to work for his good pleasure (Phil 2:12, 13).

The way Paul expresses himself here is very interesting. Here he speaks about the Philippians’ obedience to him, but he does not go on to say, “Now this is how I want you to live, or this is what I am commanding you to do.” Rather, he says, “work out your own salvation.” And this working out of their own salvation, how they are to practically do this, is not for Paul’s “good pleasure” but for God’s. Indeed, Paul can be confident that they will be able to “work out [their] own salvation” because, in fact, it is God who is at work in them, giving them both the will and the power, or ability, to live as pleases God.

In fact, the word for “salvation,” sōtēria, is an interesting one to reflect on in the light of the current pandemic. It can also be translated as “deliverance,” “protection,” and was used in secular Greek to refer, for instance, to deliverance from physical death. The verb to which it is related, sōzō, besides meaning to “save from death,” also could mean to “save, or free from disease.” In the passive form, it meant to be restored to health, or to get well.[10] In the Gospels, the verb was used to refer to the healing of someone (see e.g. Mark 5:34; 10:52). Commenting on Phil 2:12, Gerald Hawthorne writes:

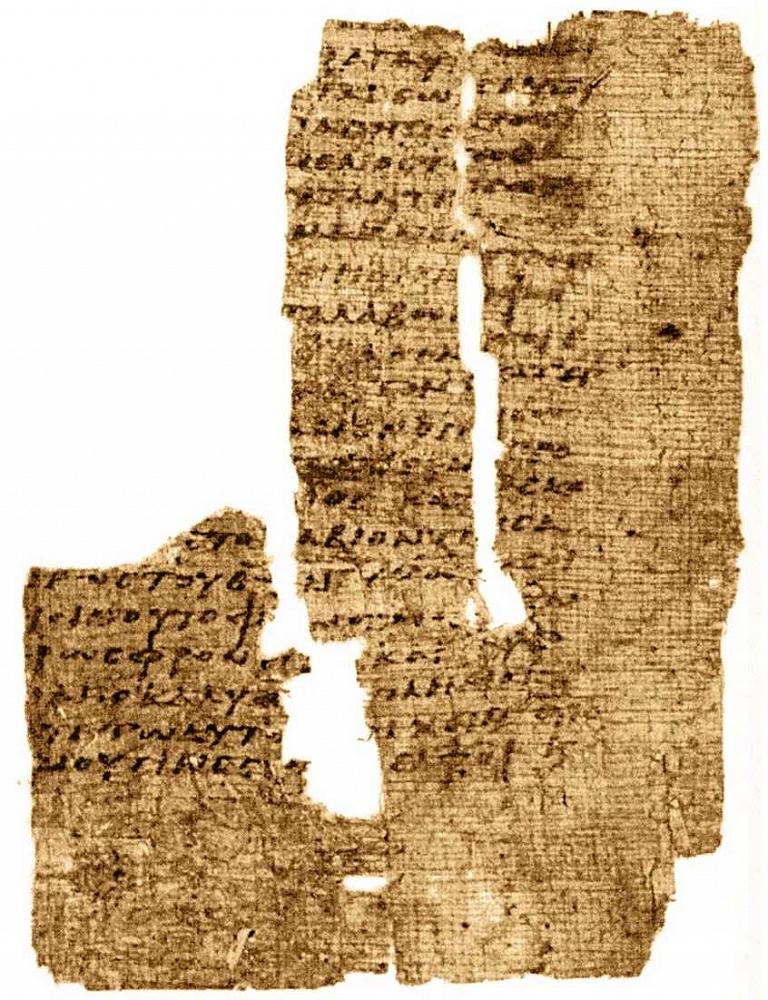

In the papyri [sōtēria] (“salvation”) is commonly used to convey the ideas of health and well-being, ideas that are not unknown to the writers of the NT (Mark 3:4; Acts 4:9; 14:9, 27:34...).[11]

Hawthorne also makes the point that the verb for “work out” and the pronoun in the phrase “your own” are both in the plural, which means that this was directed not simply at individuals, but was to operate also “in the common life together as a community.”[12]

In combatting COVID-19, we have frequently been urged to take responsibility for our own health and wellbeing, not only as individuals, e.g., to wash our hands frequently, observe coughing and sneezing etiquette, but also within our bubbles and as communities. We are reminded that what we do, how we behave, affects not just our own health and wellbeing, but that of others as well, especially the most vulnerable. We are to “stay at home” in order to stop “community transmission.” In a very real sense, we are to “work out our own wellbeing and health,” to put it in terms of health: and, for those with the virus, acting responsibly, adopting “self-isolation” may literally be in order to save themselves or others from death. We are “all in this together” when it comes to defeating a death-dealing disease. The rules are there, and we are reminded that they are there, for the good of our communal lives.

Of course, all is not sweetness and light. Paul faces his own opponents and those who are far from “obedient” to him (Phil 1:15–17). The Philippian church have those, either within their ranks or coming in from outside, who unsettle the believers. In Phil 3:2–4, Paul uses some very strong language to address an issue particular to his first-century context: that is Jewish believers who are insisting that Gentile believers be circumcised.[13] In our own current crisis, we have those who are breaking the rules, and the police are authorised to take a hard line where necessary. But other issues and problems are being exposed, or exacerbated by the pandemic: some employers are apparently misappropriating monies intended to subsidize workers’ wages, there is an increase in the incidence and the reporting of domestic violence. These, and other issues, are matters which require strong and appropriate responses. They are matters about which we need to pray; and, perhaps, when necessary, enable intervention by reporting, or when possible, supporting and standing up for those who are victims.

Philippians and our own mental health and emotional wellbeing.

The letter to the Philippians is full of encouragement, of exhortations and spiritual advice, which addresses emotions such as anxiety, fear, “bad thoughts,” or even situations of tension and strife. I am sure that many Christians have turned to verses or passages in this letter for reassurance and comfort in these unsettling and uncertain times. Paul speaks about not worrying about anything, but bringing all to God in prayer (Phil 4:6); he reassures his readers of the peace of God available through Christ (4:7). He provides a strategy for thinking “positive thoughts” (4:8).

He urges two women to be reconciled to one another, or to find agreement on an issue, and calls on others to assist them to do this (4:2–3: note that, while so doing, he affirms their great contribution and the work they have done alongside him). Paul is thankful and grateful to the Philippians for all their support and help in the past. He also says that he himself has learned to do without, and well as to enjoy “the good things in life.” One of the overarching sentiments or emotions in this letter is that of joy and rejoicing.

One of the things that has, no doubt, helped during this time of anxiety and restriction has been the humour, the fun, and the downright silliness that has been shared virtually. We cannot be together, but we can encourage one another, reaching out to one another in caring and compassion, or to bring joy and laughter, to relieve anxiety or to reassure.

Paul’s letter to the Philippians is a rich resource at any time, but particularly perhaps in a time of pandemic. I have tried to draw out some of things that have spoken to me, that have struck me as pertinent as I’ve read the letter in these past weeks. There are many more riches to be drawn out from this letter than I have touched upon. Perhaps, though, this will stimulate and help your own reflection on Paul’s letter to the Philippians as we face down COVID-19.

Derek Tovey is the book review editor for Stimulus. For twenty-one years he taught New Testament at St. John’s Theological College, Auckland and in the University of Auckland. He lives in retirement with his wife, Lea, in Glen Eden, Auckland.

[1] My references are all to the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) of the Bible.

[2] On this see D. G. Reid, “Prison, Prisoner” in Dictionary of Paul and His Letters, ed. Gerald F. Hawthorne, Ralph P. Martin, Daniel G. Reid (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1993), 753.

[3] See Morna Hooker, “The Letter to the Philippians” in The New Inerpreter’s Bible, Volume XI, ed. Leander E. Keck (Nashville: Abingdon, 2000), 473–75.

[4] Hooker, “The Letter to the Philippians,” 474.

[5] Hooker, “The Letter to the Philippians,” 474.

[6] The reference to “the imperial guard” may mean that Paul is imprisoned in Rome, in the headquarters of the imperial guard, but the Greek term used, praitōrion (praetorium) might also be used for “the residency of a Roman governor in the provinces” (Hooker, “Philippians,” 488), e.g., Caesarea. Here Hooker also indicates that she sees Paul’s reference to “brothers and sisters” (1:14, NRSV) as being “other Christians.”

[7] Though many scholars see the koinōnia the Philippians offered Paul was mostly financial in nature, that they also supported Paul by supplying personnel seems to me suggested by what Paul says about Epaphroditus (Phil 2:25; and certainly Epaphroditus brought a financial gift with him when he came to Paul from Philippi, see Phil 4:18). Phil 4:2, 3 indicates that Euodia and Syntyche worked with Paul, at least while he ministered to the Philippian church.

[8] Syzygos (translated in the NRSV as “companion”) may, possibly, be a proper name (see the footnote in the NRSV here, though most scholars do not regard it as a proper name, as it is not attested elsewhere as such). Otherwise, we cannot be sure whom Paul refers to, whether it is Timothy, Epaphroditus, or someone else.

[9] On this passage as an early Christian hymn, see Hooker, “The Letter to the Philippians”, 501; Hawthorne, Philippians, Word Biblical Commentary 43 (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1983), 76–79.

[10] See on this BDAG 982-93; 985-86.

[11] Gerald R. Hawthorne, Philippians, 98.

[12] Ibid.

[13] See Hooker, “The Letter to the Philippians,” 525 (Hooker thinks Paul is writing against Christian Jews, or possibly “Gentile Judaizers”); cf. Hawthorne, Philippians, 125, who thinks they are (non-Christian) Jews.