Christianarchy

This article emerges from the influence of two friends. They are particularly passionate and provocative advocates for what is called “Christianarchy” and particularly “anarcho-capitalism” (briefly mentioned below). Engagement with them has led me to consider Christianarchy from a biblical point of view.

. In this article, mainly using Alexandre Christoyannopoulos, Christian Anarchism: A Political Commentary on the Gospel, as a basis,[1] I will first introduce Christianarchy and describe its central biblical arguments. Secondly, I will suggest possible strengths and weaknesses. I will try to do this without too much detail as most of the arguments are familiar. However, it is the blend and conclusion that is intriguing. Here, in this assessment, I will focus on the biblical issues as this is where my strength lies. Space precludes an in-depth analysis, but my hope is that this will lead to others considering Christianarchy closely—it is an idea that should be considered and critiqued. There is much more concerning political theory and theology that hopefully can also be explored in relation to the movement.

Introducing Christianarchy

“Christianarchy” is a play on the terms “Christianity” and “anarchy.” The movement is passionately Christian, hence, sees itself as an expression of orthodox Christian thought. They are also anarchists, but not in the commonly assumed revolutionary sense. Anarchy is formed from the Greek anarchia related to archē with a range of meanings including lack of a leader, lawlessness, or anarchy.[2] It entails “a belief in the abolition of all government and the organization of society on a voluntary, cooperative basis.”[3] It is to be distinguished from popular understandings of anarchy in that it repudiates the use of force or violence. It is “about pursuing the radical political implications of Christianity to the fullest extent.”[4] Christianarchy recognises God as revealed in Christ as ruler accepting his authority while rejecting that of humans.[5] There are also strands of Christianarchism including the anarcho-capitalists who advocate for “the elimination of the state in favor of self-ownership, private property, and free markets.”[6]

Central Figures

Key figures who are considered Christianarchistic include Tolstoy (1828–1910 Russia),[7] Ellul (1912–1994, France),[8] Vernard Eller (1927–2007, USA),[9] Michael Elliot,[10] and Dave Andrews (Australia, 1951–).[11] A range of others are described by Christoyannopoulos as “supporting thinkers” who did not explicitly state their support for Christian anarchism but do advocate for pacifism including Adin Ballou (1803–1890), Ched Myers (USA),[12] Walter Wink, and John Yoder (1927–1997),[13] and the Mennonite, Archie Penner.

Arguments

1. The Old Testament

While as Christoyannopoulos says, “[f]ew Christian Anarchists comment a great deal on the Old Testament, because they are often not sure what to make of it,”[14] they do utilize it to a degree. First, Mosaic politics is seen as anarchistic. The appointment of Saul as King in 1 Samuel 8 is understood as a rejection of God’s rule and his will and the idolatrous false acceptance of the worldly government in his place. As such, the “rejection of the state […] is a necessary part of declaring allegiance to God.”[15] For Ellul, “the Old Testament never in any way validates any political power.”[16] They also contend that messianic hope had “strong political overtones.”[17]

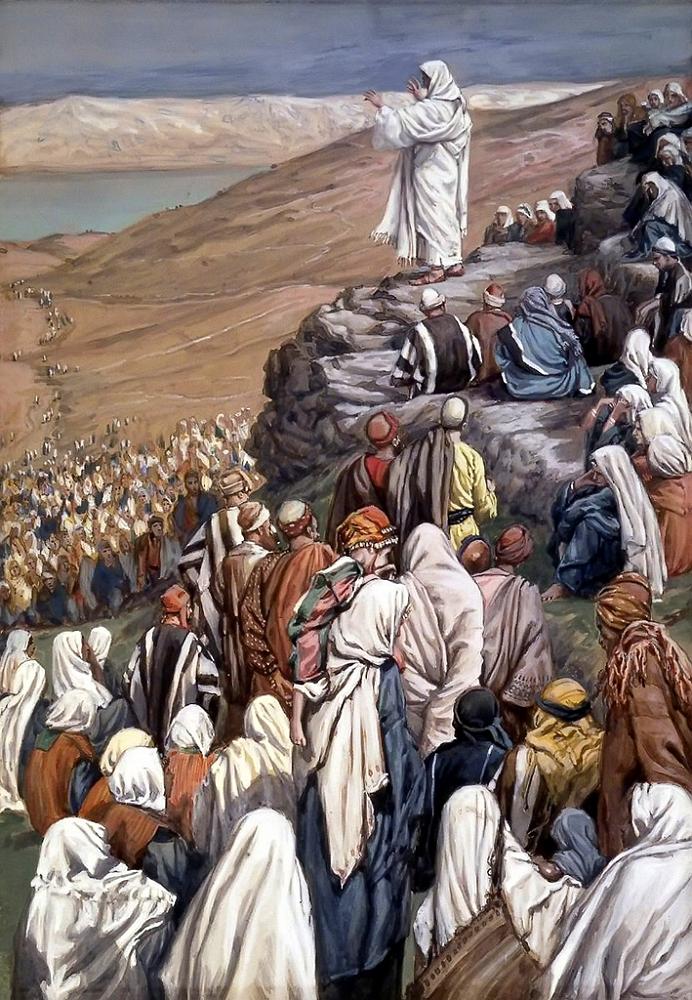

2. The Centrality of the Sermon on the Mount

Christianarchists love the Sermon (Matt 5–7; Luke 6:20–49) and interpret it literally, arguing that these are the central standard for Christian life, believing that the believer is responsible to seek to live them at all costs. This means all Christians should never resist evil with force. They are to turn the other cheek, give clothing when asked, and carry a soldier’s pack—all which disarm the assailant and stop the cycle of violence. While all agree that violent force cannot be used, Christian anarchists differ on whether this rules out nonviolent political resistance.[18] It is believed that going beyond the lex talionis stops the cycle of violence.[19] It is argued that as the state uses violence to achieve its ends, it is fatally compromised. Hence, as the Christian anarchist is utterly committed to non-violence, it cannot endorse the state in any way.[20] Tolstoy sums up well: “Government is violence, Christianity is meekness, non-resistance, love. And, therefore, government cannot be Christian, and a man who wishes to be a Christian must not serve government.”[21] Another important passage is the command to “love your enemies” which is the “litmus test of Christianity.”[22] This overcomes the cycle of hatred.[23] Such ideas are also seen as a rejection of patriotism.[24] The command not to make oaths rules out swearing allegiance to the state.[25] The Golden Rule “encapsulates the logic behind the commandment explained so far.”[26] The commands against anger are not uniformly interpreted, with some seeing justification for “righteous anger” and others repudiating anger completely. Some consider that Jesus two or three times failed to live up to his own expectations (Mark 3:5; Matt 23:17, the temple clearing).[27] The Beatitudes are a template for Christian virtue.[28] The Sermon on the Mount then is a manifesto for Christian Anarchism, which, while difficult to fulfil, must still be lived.[29]

3. Other Aspects of Jesus’ Teaching and Example

Jesus’ response to Satan’s offer of the kingdoms of the world is interpreted as a rejection of all human governments as they are demonic; one has to choose between the state and God’s rule. This is reinforced by Jesus’ comment to Peter, “get behind me Satan.”[30] Most do not comment on the miracles, but for Tolstoy, and especially the deliverance of “Legion” (Mark 5:1–20 and parr.) they speak of challenge to political power.[31] Forgiveness 490 times (Matt 18:22) means “no Caesar at all with his courts, prisons, and war.”[32] Injunctions against judgement are taken literally and absolutely as demanding forgiveness and non-retaliation and seen to rule out the use of secular courts.[33] Also important is Mark 10:35–45 which is read as a rejection of archein (human authorities) and “social hierarchies,” which is replaced by “a marginal society which will not be interested in such things, in which there will be no power, authority, or hierarchy.” Christianity is servanthood.[34] Where the clearing of the Temple is concerned, it is interpreted politically as a critique of Israel’s whole system of government. They argue there is no violence toward people in the episode. Similarly, Jesus’ statement that he came to bring division and a sword (Matt 10:34–39; Luke 12:49–53) is a prediction rather than having purposive intent.

They note Jesus’ repudiation of violence (e.g. Matt 26:52), and his non-resistance in his arrest, trial, and death.[35] There are differing views on the two swords of Luke 22:36–37, but all agree it should not be read as approval of violence.[36] The crucifixion is seen as the defeat and disarming of the powers. It is the revolution and climax of Jesus’ ministry. The cross is the pattern for Christian resistance in that “Jesus’ call for his follower to take up their cross is a call for them to follow his example of love, non-resistance and political subversion to the ultimate sacrifice.”[37] According to Christoyannopoulos, Christian Anarchists show little interest in the resurrection.[38] While they do not say much about Revelation, the two beasts of Rev 12–13 and Babylon are universalized as the state and political power.

4. The State

Christian Anarchism considers Constantine’s acceptance of Christianity and the establishment of Christendom as a fatal corruption of the Christian call whereby the faith became harnessed to the state and the use of force.[39] The modern concept of the state is viewed as fatally flawed due to its use of “violence, deception and economic exploitation.”[40] They have a radical view on violence, seeing “legislation as organized violence,” and hence, the state is delegitimized [41] The threat of violence is understood the basis of corruption. The state is idolatrous because it demands allegiance.[42] There is strong criticism of those who water down Jesus’ radical teaching on non-resistance in favour of the state and its impracticality.[43] Institutional religion is heavily critiqued, and they urge Christians to awaken in their faith.[44]

5. Romans 13 and Render to Caesar[45]

Christoyannopoulos notes first that the Christian Anarchist is suspicious of Paul because he did not always submit to Roman authorities as he preached Christ. Some, like Tolstoy and Hennacy, see Paul as mistaken and advocate outright rejection of Paul’s teaching.[46] Elliott considers that Paul’s call for submission was influenced by his expectation of an imminent parousia and the destruction of the present order.[47] For those who take Paul seriously, some take “there is no law” (Gal 5:13) as a tendency to anarchism.[48] For those who take him seriously, Romans 13 is written to the church in Rome with the intent of developing good relationships with persecutors and to avoid conflict.[49] Love for enemies involves respect for authorities. As such, Romans 13 is an example of living the Sermon on the Mount—“an ‘eloquent and passionate statement’ of the Sermon applied to the case of the state.”[50] This then is not blind obedience, worship of, or allegiance to the state. The institution of the state by God means God allows the existence of the state, as in 1 Sam 8, as it is “one of his ‘servants’ in his mysterious ordering of the cosmos.”[51] However, the state and its leaders “remain rebellious and fallen nonetheless.”[52] The state is ordained by God in the sense that it exists for non-Christians because they do not yield to God.[53] The Christian then is not to rebel against the state, but is indifferent toward it. Nor should they use violence against it.[54] Hence, while being actively critical of the state, Christians should be passively subordinate to it and not blindly obedient to it. Where its commands conflict with those of God, it is to be resisted.[55]

In Jesus’ teaching on taxes in Mark 12:13–17 and parallels, Jesus’ answer is not to be read as an endorsement of the state or the division of politics and religion, but “a counsel of subversion by indifference.”[56] Similarly, the temple tax in the fish episode of Matthew 17:24–27 is an example of not causing offence to others.[57] Christian Anarchists differ on civil disobedience, with some like Eller against it and others advocating loving and non-violent resistance.[58] The reject the use of violent resistance of any sort, and prefer revolution by example.

6. Christian Involvement in the State

Clearly, as force is required for those in many positions of state leadership, involvement in the military or other agencies of force like the police would be precluded. They also forbid holding offices of the state, which I presume, would preclude any state-run institution. If this extends to state-funded organisations, that would mean many jobs would be untenable (even Laidlaw College and playing funded international sport). They reject voting as it makes the Christian morally accountable for the decisions of the government (even if they vote against it?). Some Christian anarchists disagree with paying taxes, others reluctantly accept that they should. Such things as compulsory vaccinations and schooling are conscientiously objected to.

7. The Church

Christian Anarchists are concerned for the official church and speak of the church as “a new society within the shell of the old.”[59] This begins with repentance and then living out a political “orthopraxy,” by taking up the cross.[60] They speak of “change by conversion” rather than “through coercion.”[61] This changes comes through an “economy of care and sacrifice”[62] including the radical sharing of wealth even to the point of renouncing and selling personal poverty (cf. Acts 4:32–35).[63] Aside from anarcho-capitalists, property is not “private” but for the common good. They imagine a world in which such things as highways, bridges, schools, and hospitals are built voluntarily without the government.[64] Christianity is then a subversive anarchic political movement building a new society within the old and in opposition to the state.[65] The church then grows mysteriously like the mustard seed in Jesus’ parable (Mark 4:30–32 and parr.).[66]

A Response

There is much to like in such a view. It takes Jesus’ teaching and example seriously, recognising the radical implications of his mission. My recent work, Jesus in a World of Colliding Empires, resonates with many of these ideas.[67] Christianarchy rightly acknowledges that the call to submission in Rom 13; 1 Pet 2:13–17; Tit 3:1 cannot be absolute, as, if God and his Son rule the cosmos, our priority is yielding to their divine lordship. Advocates rightly recognise the corruption of the state in every place and the subversive role of the people of God to work within a fallen world in service of God bringing about his reign. In my opinion, it correctly challenges believers to love their enemies and do all they can to resist evil without the use of evil, leaving God to render judgment. It fairly questions what roles Christians can take within the state, and what our attitude toward the state should be. It accurately calls for cruciform orthopraxy.

However, as I consider Christianarchy, I find myself exploring these questions which point to potential weaknesses.

1. Attitude to the Old Testament and God’s Sovereignty

Christoyannopoulos states: “The Old Testament is mostly ignored, partly because the New Testament is traditionally understood to fulfil it, but mainly simply because Christian anarchists generally have very little to say about it.”[68] Where Matt 5:17–20 is in view, while there are disagreements on the degree of continuity between the teaching of Moses and Jesus, Christianarchists concur that Jesus’ teaching has priority over any Old Testament teaching.[69] Christian Anarchy has to come to terms with complex questions concerning the Old Testament writers’ consistent belief that God is actively involved in and sovereign over the politics of the world including Israel in Egypt, the cycle of the Judges, Assyria and Babylon and the exiles, Cyrus and Medo-Persia, and Rome. There are hints in the New Testament that such rule has not ended, especially as Jesus predicts the destruction of Jerusalem and apocalyptic sections point to God’s judgement in the political arena in judgment (Mark 13 and parr.). God’s people of Israel are caught up in that story, sometimes on the “winning side,” often on the “losing.” When considering Rom 13 and other such texts, these sit within that salvation historical narrative and God’s people are swept up in it. Can we simply dualise the world into governments for the heathen; God’s kingdom for believers—at least while we are living in “exile” so to speak (cf. 1 Pet 1:1; 2:11)?

Where the Old Testament is consulted, there is an almost idyllic interpretation of the anarchic time of the Judges leading to monarchy. However, this was hardly anarchic and if anything, points in the other direction. The cycle of the Judges saw Israel without adequate government fall into idolatry and decay time after time culminating in the Sodom-like rape and dissection of a woman leading to war (Judg 19) Throughout Judges, God raised leaders who established government and through them, God put things right. This is the converse of anarchy; it is anarchy leading to chaos and God’s intervention to install leadership to restore the nation. Overall, Judges moves toward anarchy to the demand for monarchy as an attempt to resolve the chaos of this period ().[70]

2. Hermeneutical Assumptions

Christoyannopoulos notes:

most Christian anarchists approach the Bible with a modern mindset, interpreting its commandments as fairly literal propositions and frequently paying little attention—in their political exegesis at least—to any layers of meaning behind the merely literal and political … they bypass traditional exegesis and rely only on scripture for their understanding of Jesus’ teaching.[71]

This is fine except that certain texts are privileged and read literally, and others not so. So, certain sections of the Gospels form a canon within the canon. This supposedly self-consciously privileges Jesus but in fact, privileges Mark, Matthew, and Luke, all of whom wrote after Paul. Why should Paul be marginalized? The hermeneutic is inconsistent with Romans 13 and other submission texts which are not read literally concerning the state (one of which was supposedly written by the Apostle Peter [1 Pet 2:13–17]). There is great criticism of Christian failure to read and apply Jesus literally; yet the same could be said of their read of Paul and Peter. In my opinion, Christianarchists make a similar mistake to those who privilege certain texts on women concluding women cannot minister in churches. They do so by diminishing the value of a range of texts that qualify and challenge these extreme statements theologically.

3. Lack of Critical Engagement

Christoyannopoulos writes, “By and large, they ignore traditional commentaries” in their exegesis.[72] I find this disappointing and leaves their exegetical approach open to serious challenge.

First, of all, there is almost no engagement with the historical, cultural, and social contexts of the New Testament. For example, assuming standard traditional authorship and dating for Romans and 1 Peter, they fall in Nero’s reign and at different points (Romans in the “good years” of the late 50s, 1 Peter when Nero was going astray). Yet, this is not considered when discussing these texts. Exegetical assessment of Greek is absent such as hypotassō used in a range of relevant New Testament texts (Rom 13:1, 5; 1 Pet 2:13; Tit 3:1). It is fair enough to note that Christ is Lord, and these commands do not endorse absolute allegiance to the point of denying one’s primary obligation in Christ. Yet, it is another thing to push this as far as saying that it is merely subversive and has no more than ironic force. Can hypotassō, which can have absolute force in Paul and Peter, be written off in these passages merely as irony? (1 Cor 15:27–28; Eph 1:22; 5:24; Phil 3:21, 1 Pet 3:22).

Similarly, Myers is cited by Christoyannopoulos as anarchistic, yet Myers actually says here what is traditionally read of the Mark 10:35–45: “Jesus does not here repudiate the vocation of leadership, but rather insists that it is not transferred executively.”[73] The Markan passage then speaks against a type of leadership not all leadership or governments. Similarly, the injunctions against judgement through the New Testament speak against a particular type of absolute judgment, while believers are always meant to discern and make judgments.

4. Other Things

There are a range of other questions. Is the Kingdom of God itself stateless and leaderless? God appoints apostles, teachers, pastors, evangelists, elders, deacons, and other leaders (e.g., Eph 4:11; 1 Tim 3:1–13). They lead. They govern. There is then a government? Is this a vision for some kind of anarchy?

If Christians are not to be involved in the machine of the state, how far does that go? There is clear evidence in the NT of at least one person in the employ of the local government, Erastus, the city treasurer of Corinth (Rom 16:23).[74] Philippians 1:13 may indicate there were Christian soldiers in Rome and the descriptor “those from Caesar’s household” in Phil 4:22 may be code referring to some who worked in Caesar’s inner circle in Rome.[75] How do we reconcile this with a view that Christians should not be engaged in the government?

Other questions can also be raised. Can a Christian work for an organisation that takes government funding? Can a sick Christian go to hospital? Can a Christian under attack call the police? Can a Christian be an anarchist and drive on roads built by governments, central or local? Can they fill their cars with petrol, when a good portion of the payment is taxed? Can a Christian work for an organisation that is under government approval, such as NZQA approved institutions?

How far does non-violence go? Can a Christian come to aid of a women being raped, and use necessary force to remove the person? What is love? Is love always non-violent? Is there a time for violent force in the service of the vulnerable and violently oppressed? What do we make of consistent pictures of eschatological destruction?

Is the modern state in all its forms so utterly corrupted that Christians should separate from it? For example, one can understand Tolstoy’s radical response to Czarist Russia. One can acknowledge a repudiation of patriotism in states which have such a high view of the flag and constitution. Yet, to suggest that all states are equally heinous and suggest a once-for-all response to all governments in all situations in the same way, seems naïve.

It is believed that Christians in withdrawing from state involvement can build a society within the shell of the other that can meet the demands of the world. To me this is also naïve. If government is abandoned, then evil will often hold sway.

Conclusion

Christian thinkers should take Christianarchy seriously. Presently, it is mainly an internet phenomenon without a great intellectual undergirding. Yet, for some, it is a viable option for Christians living in a fallen world. As such, I would encourage its proponents to continue to articulate their views in conversation with the whole breadth of Christian scholarship so that we can consider it more thoroughly. I would also urge others to consider Christianarchy and respond to it from their theological perspectives. I believe the movement has much to say to challenge our view of the state. The state is never infallible and is not the answer to every question. Still, I am not convinced that we are all called to completely withdraw from involvement in the state, nor is that even possible in a world where the state is so intrusive. Yet, Christianarchy is a fascinating means to consider how best to answer the question: what is a Christians relationship with the state?

Mark Keown is the co-editor of Stimulus and New Testament Lecturer at Laidlaw College. His recent publications include The Philippians EEC Commentary, Jesus in the World of Colliding Empires and Discovering the New Testament.

[1] Alexandre Christoyannopoulos, Christian Anarchism: A Political Commentary on the Gospel (Abridged Edition) (Exeter, UK: Imprint Academic, 2013 (Digital Version). (Thereafter, AC, CA)

[2] LSJ, 120.

[3] Soanes, Catherine, and Angus Stevenson, eds. Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

[4] AC, CA, Loc. 54.

[5] AC, CA, Loc. 167.

[6] “Anarcho-capitalism,” in Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anarcho-capitalism.

[7] See the summary in AC, CA, Loc. 328–74.

[8] Jacques Ellul, Anarchy and Christianity, trans. George W. Bromiley (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1991). See the summary in AC, CA, 374–86. He cites Ellul, “the anarchist position [is] the only acceptable stance in the modern world” (Ellul, Anarchism and Christianity, 156).

[9] See AC, CA, Loc. 386–98. See Vernard Eller, Christian Anarchy: Jesus’ Primacy over the Powers (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1987). His exegesis of Rom 13 and Mark 12:17 as subversive is important. He is rejected by some because of his view of submission to state.

[10] See AC, CA, Loc. 398–410. See Michael C. Elliott, Freedom, Justice and Christian Counter-Culture, (Eugene, OR.: Wipf and Stock, 2013).

[11] See AC, CA, Loc. 410–421. Dave Andrews, Christ-Anarchy: Discovering a Radical Spirituality of Compassion (Eugene, OR.: Wipf and Stock, 1999).

[12] Ched Myers, Binding the Strong Man: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1988).

[13] John Howard Yoder, The Politics of Jesus (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1994), esp. Ch. 1. Other writers include some from the Catholic Worker Movement (Loc. 421–86), other anarchist publications (Loc. 486–576) (including William Cavanagh).

[14] AC, CA, Loc. 2189.

[15] AC, CA, Loc. 2199–2294.

[16] AC, CA, Loc. 2337.

[17] AC, CA, Loc. 2366.

[18] AC, CA, 896–998.

[19] AC, CA, 998–1202.

[20] AC, CA, 1202–1256.

[21] AC, CA, Loc. 1288–91.

[22] AC, CA, Loc. 1347.

[23] AC, CA, Loc. 1414.

[24] AC, CA, Loc. 1374.

[25] AC, CA, Loc. 1427–91.

[26] AC, CA, Loc. 1505.

[27] AC, CA, Loc. 1518–1597.

[28] AC, CA, Loc. 1610–38.

[29] AC, CA, Loc. 1758–88.

[30] AC, CA, Loc. 2366–2437.

[31] AC, CA, Loc. 2437–62.

[32] AC, CA, Loc. 2477. The citation is from Ammon Hennacy, The Book of Ammon (Baltimore, MD: Fortkamp, 1994), 43.

[33] AC, CA, Loc. 2506–60. This is drawn in part from John 7:53–8:12, and no discussion concerning textual variants.

[34] AC, CA, Loc. 2560–2604

[35] AC, CA, Loc. 2691–3007.

[36] AC, CA, Loc. 2721–61. Tolstoy and Hennacy suggest Jesus is tired and hesitant. Ellul and Ballou consider two swords is irony as it could not be enough for a rebellion, and so are to be used for other purposes such as preparing the meal (Penner).

[37] AC, CA, Loc. 2993.

[38] AC, CA, Loc. 3007.

[39] AC, CA, Loc. 3717–3843.

[40] AC, CA, Loc. 3885. This is fleshed out in Loc. 3885–4138.

[41] AC, CA, Loc. 3920.

[42] AC, CA, Loc. 4138–4208.

[43] AC, CA, Loc. 4260–4579.

[44] AC, CA, Loc. 4579–4634.

[45] While there is no real developed discussion of 1 Pet 2:13–17 and Tit 3:1, Romans 13 is taken as the core text and discussed with the implication that these passages should be read the same way.

[46] AC, CA, Loc. 5135.

[47] AC, CA, Loc. 5135.

[48] AC, CA, Loc. 5149 notes some uses “there is no law” from Gal 5:13 as a basis for anarchism.

[49] AC, CA, Loc. 5162.

[50] AC, CA, Loc. 5173.

[51] AC, CA, Loc. 5203.

[52] AC, CA, Loc. 5232.

[53] AC, CA, Loc. 5247.

[54] AC, CA, Loc. 5247–5259.

[55] AC, CA, Loc. 5272–5301.

[56] AC, CA, Loc. 5339–5382.

[57] AC, CA, Loc. 5396–5424.

[58] AC, CA, Loc. 5440–5480.

[59] AC, CA, Loc. 6029.

[60] AC, CA, Loc. 6054. This is a phrase from Myers, Binding, 285.

[61] AC, CA, Loc. 6085. This comes from Dave Andrews, Not Religion, but Love: Practicing a Radical Spirituality of Compassion (Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim, 2001), 65.

[62] AC, CA, Loc. 6085.

[63] AC, CA, Loc. 6085–6161.

[64] AC, CA. Loc. 6146–6161.

[65] AC, CA, Loc. 6178–6236.

[66] AC, CA, Loc. 6475–6541.

[67] Mark J. Keown, Jesus in a World of Colliding Empires: Mark’s Jesus from the Perspective of Power and Expectations, 2 vols (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2017).

[68] AC, CA, Loc. 293. Similarly, the Apocrypha is not considered, see n. 42.

[69] AC, CA, Loc. 1652–1746.

[70] Of note is the repeated refrain concerning the absence of a king (Judg 19:1; 21:25) leading to the demand in 1 Sam 8.

[71] AC, CA, Loc. 304.

[72] AC, CA, Loc. 2177.

[73] Myers, Binding, 278.

[74] Erastus may also be the same as that of the Erastus inscription found at Corinth. See Douglas J. Moo, The Letter to the Romans, NICNT Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018), 952 who considers that it is the same person “probable.”

[75] As I have argued in Mark J. Keown, Philippians, EEC (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2017), 1:187–89; 2:472–77.