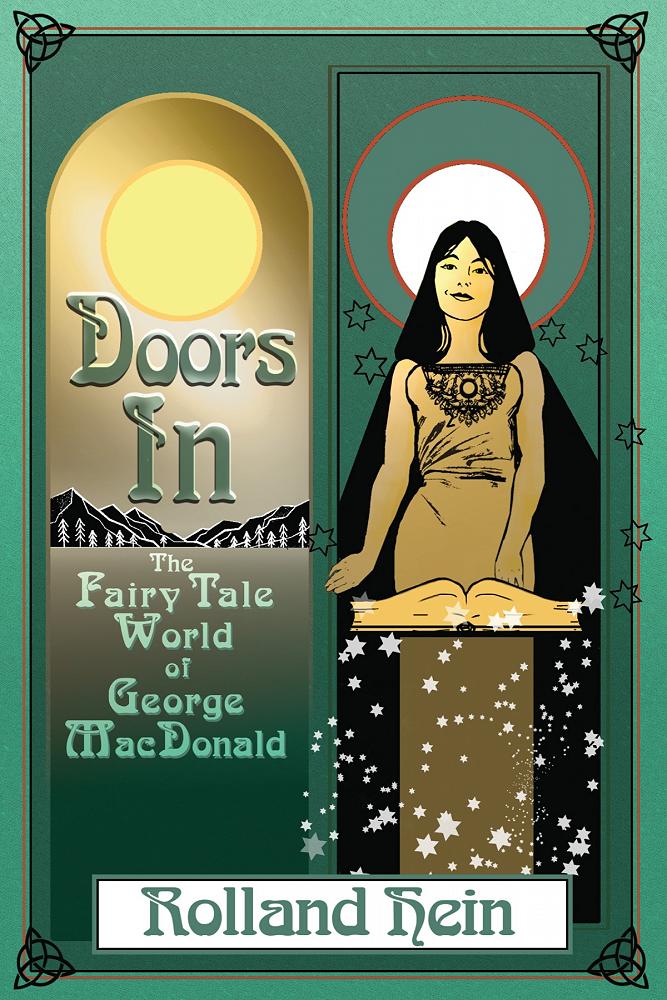

Book Review: Doors In: The Fairy Tale World of George MacDonald

Rolland Hein

“I have had a great literary experience this week,” proclaimed C. S. Lewis in a letter to his friend Arthur Greeves dated 1916 (10). Lewis was referring to George MacDonald’s fantasy novel Phantastes. MacDonald’s influence on Lewis’s own fictional work cannot be overstated and it is no surprise Lewis was drawn to MacDonald’s work. In MacDonald, Lewis found a kindred spirit, a compatriot and champion of the power of the imagination, and a fellow traveller in the spiritually charged realm of Fairy Land. In fact, Lewis repaid his literary debt to MacDonald some years later when MacDonald appeared in Lewis’s fantasy novel The Great Divorce. In that work, as Lewis traverses the afterlife, he meets MacDonald, and in a tone of respect and admiration he tells MacDonald that upon reading his work he felt he had begun his “New life.” It is testament to MacDonald’s spiritual insight and literary skill that Lewis considered himself not merely a fan, but a disciple. This story is recounted in Rolland Hein’s new book Doors In: The Fairy Tale World of George MacDonald, a deeply satisfying exploration of MacDonald’s adult fairy tales.

Born in Scotland in 1824, MacDonald was an early figure in what was then a new burgeoning literary style called ‘fantasy literature.’ In fact, Hein tells us MacDonald was mentor to a then little-known up-and-coming writer by the name of Lewis Carroll. Carroll, of course, would go on to write some of the most enduring works of literature in the English language, the best-known being Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

MacDonald himself was a committed Christian, a minister in the Congregational Church and, while certainly not typical, a theologian in the same rank of a C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, and G. K. Chesterton. Nonetheless, Hein is aware many readers will be unfamiliar with MacDonald’s work and does a wonderful job introducing new and curious readers to MacDonald’s highly stylized fantasy worlds, which on first reading can be difficult to penetrate due to their symbolic nature and dense, elevated (some might describe it as formal) tone. At the same time, those familiar with MacDonald’s dream-like-tales will welcome Hein’s guidance into the deeper landscapes of these fairy worlds; knowing full well there are riches to be had. But without an expert to lead them, even an engaged reader may lose their way or give up altogether.

Hein is Emeritus Professor of English at Wheaton College, and has written five books on MacDonald ranging from the scholarly to the devotional, so if the reader needs a guide, they will struggle to find one more qualified than Hein. And like all good guides, Hein is not interested in dazzling the reader with his erudition, but ushering them into a new world, one he hopes will capture the imagination as much as the intellect. The book then is clearly aimed at the general reader and not the scholar. This, I think, is one of the book’s strengths. In the same way Hein recommends approaching MacDonald’s fairy tales, the reader must come to this book not looking for mere intellectual stimulation, but to engage Hein’s elucidations as one experiences a work of art – open to wonder, for just as fantasy must be experienced to be understood, so too this book.

To understand MacDonald’s stories, first you must know what concerned MacDonald, advises Hein. MacDonald looked at the religion of his day and saw a community slowly petrifying under the pressure to package the faith in such a way so as to be acceptable to the rationalism of the day. The German philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein defined the cultural climate of the day when he said, “The world is all that is the case.” MacDonald believed this had led to the neglect of the imagination and the vital role it plays in bringing both believer and non-believer into a deeper relationship with God. MacDonald sought to reawaken his readers to the power of the imagination and, just as importantly, the supernatural, which he refers to by the metaphor Land of Faerie.

It is no surprise then that his first book Phantastes opens with this very question: Does the Land of Faerie exist and if so, what is its nature? The main protagonist in the book, Anodos, represents the mentality of the day: totally unaware of the spiritual reality shining all around him. An unexpected event (as is often the case) propels him to embark on a metaphysical journey that will ultimately bring these two worlds together for him in the most satisfying way. Hein’s reminds us that we are dealing with fairy, so not everything will make sense right away, especially if we too are unaware or only just starting out on a journey towards a more sacramental view of reality, or Faerie Land. While sorting through his late Father’s papers, Anodos is greeted by a “tiny woman-form” who challenges his material view of the world and tells him he will make his way into Fairy Land the next day. The strange meeting fills him with “an unknown longing” (11). Turning to gaze out the window at the moonlight, he is suddenly aware of a thick fog hanging in the air, which was not present before, which he perceives as an “all-encompassing sea” enveloping the night. The fog appears to be symbolic of a burgeoning new state of mind. Hein’s tells us that MacDonald had a “profound knowledge of Scripture” that had permeated imagination (12). In the background of this strange encounter, Hein suggests, we might detect the Letter to the Hebrews “saying ‘by faith we understand that the universe was created by the word of God, so that what is seen was not made out of things that are visible’” or perhaps the Letter to the Corinthians in which Paul says “we look not to the things that are seen but the things that are unseen. For the things that are seen are transient, but the things that are unseen are eternal” (12).

Hein guides the reader through all eight of MacDonald’s adult fantasies, devoting a chapter to each: Phantastes, The Light Princess, The Princess and the Goblin, The Princess and Curdie, The Wise Woman, or Double Story, At the Back of the North Wind, The Golden Key: The Borders of Fairyland, and Lilith.

Not every reader will appreciate the ambiguity of MacDonald’s fairy tales or Hein’s equally elusive readings. Those looking for pat answers to theological or philosophy questions will either be frustrated or disappointed. MacDonald was not interested in allegorising the Christian faith but penetrating to its essence. Hein tells us it took MacDonald five years to write his final tale with many revisions. Multiple times during this period his publisher requested a summary of the book’s meaning, which MacDonald refused. In reply he wrote, “It cannot help having a meaning, but one man will read one meaning in it, another will read another … A genuine work of art must mean many things; the truer its art, the more things it will mean” (84). Hein tells us that such multiplicity was vitally important to MacDonald who believed that the multiplicity allowed for the greatest chance for God to meet the reader in the story wherever they may be on their spiritual journey. To narrow down its meaning would be to restrict the work of the Spirit. This type of deep excavation takes risk of course – the message may be lost entirely – but with great risk comes great reward, of which there are many in this book, if one is willing to journey with Hein and MacDonald.

All of MacDonald’s fairy tales are shot through with this wonderful mixture of the material and the spiritual. As a result, after reading MacDonald’s fantasies the reader is likely to come away with a new sense of the world as a truly numinous place, which as Hein believes, is exactly the desired effect.

Jonathan Hoskin is a PhD candidate at AUT. His work focuses on the intersection between philosophy, theology, and literature.