Narratives of Despair, Imaginations of Hope

Within the first week of the emergence of the COVID-19 outbreak, Stephen Soderbergh’s apocalyptic thriller, Contagion,was reported to have been Warner Bro’s most in-demand movie, behind the Harry Potter franchise.[2] This recent surge in the movie’s popularity, in which a deadly global virus spreads via respiratory droplets, suggests that people are wanting to place our frightening new predicament into a narrative. We want to be able to know where we are in the drama and how long we have to look at empty streets, experiencing each other through windows and screens. We are searching for ways to locate ourselves in a story and we want to know how this whole thing ends.

In short, we are looking for ways to form our imaginations so that we can live accordingly. We want to know how to live well when life itself seems to have gone dramatically off-script. Are we in the opening montage of palatable establishing shots before everything goes haywire and this movie of ours descends into an apocalyptic nightmare? We don’t know.

While there are many lines of reason in the way of expert predictions, almost everyone seems to agree that the world will never be the same and we should expect difficult days ahead economically, geo-politically, and in terms of infrastructure. Disparities between the haves and the have-nots will be far more evident as businesses begin running much more efficiently with fewer people and with smaller real estate footprints.[3] The working middle class will be the ones hit the hardest as we streamline in these ways and fresh social tensions will inevitably rise in its wake. We should expect a surge in national protective measures as borders shut and suspicions rise alongside a renewed sense of self-preservation and nationalism across the globe. As Robert Kaplan observes, “In sum, it is a story about new and re-emerging global divisions, more friendly to pessimists.”[4]

In a very real sense, this virus has put global tensions on fast forward; globalisation was already buckling under the weight of its own aspirations as it saw populist leaders emerge across the world, riding new waves of exclusivism and fear directed at the “other.” Amy Chua, while explaining these global trends, notes that “when groups feel threatened, they retreat into tribalism. They close ranks and become more insular, more defensive, more punitive, more us-versus-them.”[5]

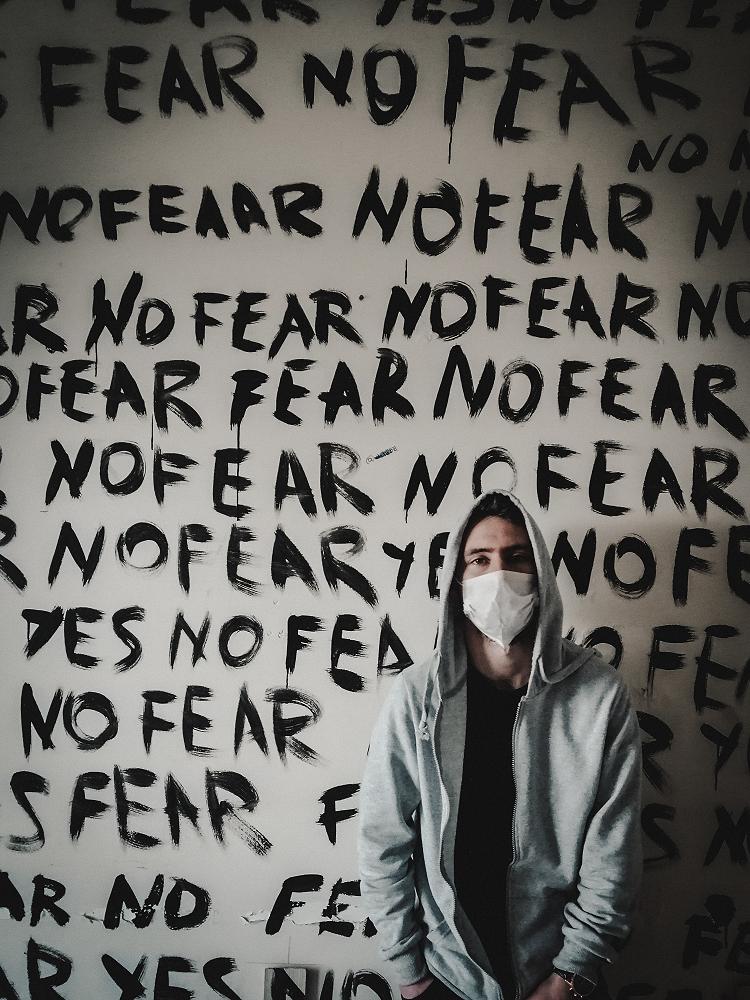

We have seen this working its way through much of the journalism written during this lockdown with fingers pointing at entire countries or political bodies. Unavoidably, we have now adopted this insularity on a personal level as we recognise that this insidious, invisible threat could be at work in every passing stranger’s body. Our imaginations are slowly being trained to see every other human as the ultimate “other”; a real threat to our livelihoods and a danger to even our lives. While distancing behaviour is vital, we must be highly proactive in limiting the way we let these separating practices form our imaginations and resist the temptation of exclusion as a lens on human interactions. The negotiations we make every day around the difficult balance of connection and separation have had to swing to the latter dramatically.

It would be all too easy to have our imaginations formed by fear. So much is new to us and out of our control. We have never been in a harsh lockdown before. We have never had international border restrictions like this. We have never had a medical threat restrict us from seeing our loved ones at this scale or from (heaven forbid) buying a Big Mac Combo. We have never felt vulnerable in this way watching so many celebrities and notable names succumb and even die due to a pandemic, reminding us almost daily that no one is safe from this. We have never seen our economies brought to their knees in this way, with so many of us now unsure about income and job security. Crises tend to turn us inward and give us a self-centred tunnel vision nationally and personally. How easy it would be to live according to fear in this time!

But that is not our story. While it might be a first for many of us, this is not the first time the church has faced a plague. Looking back into our history, we see remarkable instances of the way in which Christian communities have responded in times coloured by great fear. Towards the end of the second century, the “Plague of Galen” struck the Roman Empire with devastating consequences. The epidemic meant that an estimated quarter to a third of the population lost their lives in this time with many routinely found dead in fields.[6] It was considered completely reasonable for someone to flee during this time, leaving the victims to fend for themselves and to secure one’s own safety.

Yet the Christians of this time actively cared for the sick and dying, often at the expense of their own health, neither fearing sickness or death. While this is not a call for all of us to risk our own health, it does speak volumes for the narrative that our forebears were living by; a reality in which death did not have the final word. One only needs to recall the way in which the emperor Julian disgustedly observed: “those impious Galileans”[7] tending to the poor to realise how visible this different way of being was in times of crisis.

Rodney Stark argues that during this plague,

the Christians were certain that this life was but prelude … to have remained in Rome to treat the afflicted would have required bravery far beyond that needed by Christians to do likewise.[8]

Stark’s observation here is that risking one’s health for the sake of the needy is not as troublesome for those to whom death no longer commands ultimate consideration. The point is that when we take the claims of the gospel seriously, that death has indeed been conquered, then even the most pressing of threats is seen for what it is - temporary. It is in this light that we make room in our imaginations for something that speaks louder than despair in times of great tumult - hope.

Christian hope is not the empty platitudes of an inspirational Instagram post or the detached philosophy of much of new age spirituality. Jürgen Moltmann describes this hope as a “presentative eschatology,” an expectation of what will come that “sets about criticising and transforming the present.”[9] It is a hope that acts now as a demonstration of what is to come, that brings the final chapter into the present one in joy and hopeful activity. It animates us through the Spirit to respond to it creatively as we trust in the one that embodies a coming yet already initiated new creation.

In this way, eschatology is not so much just the end of things, but the beginning of them too. It generates in us now a “passion for the possible,”[10] to see things made new, because this vision is one in which everything is made right in the end. We work for good because we know the ending is a good one! While we lament with those who have lost and take seriously all the precautions we have to take out of love, we do so hopefully and in peace knowing that not even death can separate us from the love of God. We can mourn in the face of death while still asking the question, “O Death, where is your sting?” (1 Cor 15:55; Hos 13:14) If we can demonstrate this hope in palpable ways in this climate of great fear and separation, it will stand out in ways that may not have been as visible when everything was going as normal.

This is not a case of posturing; the world needs to see narratives of hope in action. Political polarisation and xenophobia will continue to escalate.[11] Political capitalisation based on the missteps of our leaders will continue to occur. Different forms of isolation will continue to influence the practices of human relationships. Finger pointing, demonizing, and scapegoating will continue. Death will continue to plague our imaginations. We will continue to look for pandemic narratives, and find grim predictions in the worlds of World War Z, I Am Legend, Planet of the Apes, and 28 Days Later and see little in these visions of community to inspire anything beyond a primal survival instinct. All of this speaks of a world in which death indeed has the final word, and distrust is the modus operandi. To walk in peace and hope in acts of love will be a radical departure from this backdrop of despair and exclusion.

Jesus commands his followers to not fear the one who kills the body, but who cannot kill the soul (Matt 10:28). This Coronavirus certainly falls into this category. But it is easier said than done to suggest to people that they should not fear. I have seen many posts online expounding the neurological disadvantages of anxious habits while reminding readers of the benefits of positive thinking and practices of gratitude; habits of the mind that can transform our life experiences. While these utilitarian arguments remind us that perception is a choice, they betray the reality of a materialist mentality: if death has not been defeated, then it most certainly should be feared. It is the end game. It is the final word. Whenever we see a command in Scripture to not fear, however, it is always connected to the reality that we can do this precisely because there is someone who cares for us.[12] It is not just a choice to adopt a state of mind in order to improve our mental well-being but a choice to trust in a person who has overcome our very worst fears, someone who has conquered both death and suffering. It is to join our brothers and sisters in the early church who also confronted deadly plagues to assert that although we need to take it seriously, we take the victory of Christ to be of greater consequence.

So, what might this hope look like in practice? In a time of increased financial instability and anxiety, it will look like generosity; giving when it would be all too easy to look after our own and stockpile. To look outward to the needs of others shows that we trust that our generous God is greater than any monetary outcome we may endure. It will look like a generous spirit towards our leaders in times when it is incredibly difficult to make the right decision and unforeseen consequences are bound to emerge no matter what decision is made. It will appear as gratitude and a discipline of thankfulness at a time in which we are made more aware than usual of what we are lacking and what has been taken away, for some permanently. It will make itself known as peace, knowing that even though we are hard pressed, perplexed and struck down, we won’t be crushed, in despair, abandoned, or destroyed (2 Cor 4:8–9).

This hope is an active non-anxious presence in the world, a reminder that we stand in a very different story of the world, one that does not end in a post-apocalyptic wasteland with civilization in ruins and humanity trying to find a semblance of meaning. It ends better than it had ever looked before because there is One who has made it new and has moved in with us to stay, the final “bubble” in which no fear resides and all of creation dwells.

So in this time, we don’t just guard our imaginations, we fill them with the true vision, one that has been shaping this strange and contrary community for two millennia, one that continues to offer a better story to the world and lives expectantly in our modes of being.[13] At a time when other narratives like globalism, capitalism, or even busyness have lost their grip on our imaginations in the most abrupt way, let us walk clearly to a different rhythm in faith, that there is One who may take our small deeds of hope and make them a part of the best story of all.

Sam Burrows is a lecturer at Laidlaw College in the School of Education where he lectures in a mixture of theology and education based papers. Sam has many years of teaching experience including experience as a deputy principal and is currently completing his Master of Theology at Laidlaw College.

[1] Frederick Buechner, Beyond Words: Daily Readings in the ABC’s of Faith (New York: HarperCollins, 2004), 160.

[2] Jacob Stolworthy, “Contagion becomes one of most-watched films online in wake of coronavirus pandemic”, Independent, https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/news/contagion-coronavirus-download-watch-online-otorrent-warner-bros-cast-twitter-a9403256.html.

[3] Ian Bremmer, “The ‘New Normal’ After COVID-19,” GZERO, https://www.gzeromedia.com/the-new-normal-after-covid-19.

[4] Robert D. Kaplan, ‘’Coronavirus Ushers in the Globalization We Were Afraid Of,” Bloomberg (March 21 2020),

[5] Amy Chua, Political Tribes (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), 8.

[6] Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Force in the Western World in a Few Centuries (San Francisco, CA: HarperCollins, 1997), see chapter 4.

[7] Stark, The Rise, 84.

[8] Stark, The Rise, 88.

[9] Jürgen Moltmann, Theology of Hope (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. 1993), 335.

[10] Moltmann, Theology of Hope, 35.

[11] Thomas Wright, “Stretching the International Order to Its Breaking Point”, The Atlantic,

[12] Miroslav Volf, “How to Be Afraid: Easter in the Time of COVID-19,” For The Life Of The World Podcast. Yale Center for Faith and Culture, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/how-to-be-afraid-easter-in-the-time-of-covid-19-miroslav-volf/id1505076294?i=1000471158742.

[13] Michale J. Sleasman, “Swords, Sandals, and Saviors: Visions of Hope in Ridly Scott’s Gladiator,” in Everyday Theology: How to Read Cultural Texts and Interpret Trends, ed. Kevin J. Vanhoozer, Charles A. Anderson, and Michael J. Sleasman (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2007), 147.