When kelp needs help: saving our sea forests

Rimurimu are critical to the health of our coastal marine environments. They form underwater forests that provide shelter and food for the creatures that feed the fish we eat, and they help reduce the impact of climate change and ocean pollution by soaking up carbon and nitrogen.

Giant kelp, which loves the cold waters of Aotearoa, is the fastest-growing organism in the world as it can lengthen by as much as 60cm in a day. However this doesn’t apply if the spores can’t develop in the first place – one of the many problems seaweeds are facing today.

That is why tauira (students) across Te Upoko o te Ika a Māui (Wellington region) are taking part in a new initiative run by Mountains to Sea Wellington called 'Love Rimurimu', in which they are learning about the hidden world of rimurimu and what they can do to help keep our unique kelp forests healthy.

“There are many human impacts affecting seaweed in Wellington - from sewage leaks to boat anchors ripping seaweed from the seabed,” says programme coordinator Jorge Jimenez Senen. “However, the biggest threat right now is global warming. This will make Wellington's waters too hot to sustain healthy giant kelp forests as they only like colder waters.”

Jorge, who has a Masters in marine conservation, says that he and his team looked for giant kelp spores over the winter of 2020 but could not find any, as the spores had already been released. This suggests that the warmer winter this year had changed the timings of the Giant Kelp reproduction cycle, in which sporing happened sooner than expected due to the water warming up earlier than normal.

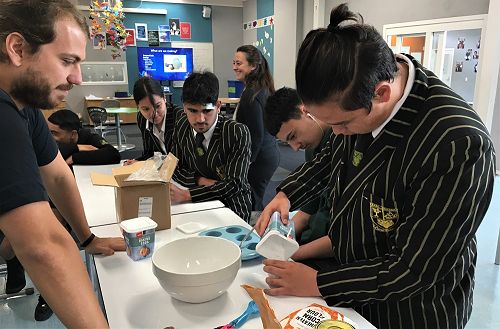

As well as conducting experiments looking at seaweed photosynthesis (turning sunlight and carbon dioxide into sugars and oxygen), the students have also been attempting to harvest rimurimu spores and grow them in their classroom. This has proven trickier than expected due to the warm winter, with only one school group so far – Mana College in Porirua – being able to find spores and then successfully germinate them in their classroom tank.

Zoe Studd, Mountains to Sea Wellington Director, says that the COVID-19 restrictions in early 2020 brought along a new set of challenges that all the project organisers and participants had to work through – but not all of them were bad.

“We had to quickly turn everything into an online format for the teachers and students, which was a real challenge as we had not really done that before," she says.

"Surprisingly, it was actually easier than normal to arrange for the scientists and other experts to take part in lessons with the students. Most were more available for the virtual meetings because they were working from home rather than having to travel in from their offices or laboratories.”

Once the restrictions lifted, the team began running other activities for the students, such as making cosmetics, food, bioplastics and fertilisers with rimurimu as the main ingredient.

“It’s made me see things differently outside of school now – like, when I’m brushing my teeth I think about how the toothpaste actually has seaweed in it,” says Elliot, 16, from Mana College. “It’s also been really interesting seeing the seaweed spores grow in our tank, as I didn’t expect them to.”

Karena, 16, adds, “I really like that we can use seaweed to create more sustainable products, like the bath bombs we made today, but for me the best part has been being able to grow the spores in the tank. We will keep growing these over the next few months and then we will put them back into the sea.”

Jorge explains that Porirua has a big problem with sedimentation, rubbish and pollution from storm water. The sedimentation means that particles suspended in the water along Porirua’s coastline act as sandpaper, damaging and ripping the spores off the rocks where they are settling.

Transplanting adult rimurimu from the tank to Porirua’s coastline could help bypass this problem, Jorge says. “But we are growing the spores in nearly sterile conditions so it will be interesting to see how they would cope with all the nasty stuff found in Porirua’s waters.”

Marina Anderton, Year 12 Dean and Marine Studies teacher at Mana College, says that she was keen to get her students involved in the project because it fit her goals of connecting people with place.

“I find that this helps students learn science in a more relevant way and get a deeper understanding of how our individual actions can affect our local community and environment.”

Jorge adds, “It’s been really cool seeing the students’ faces light up when there’s a shift in how they think about seaweed. Some have gone from them thinking about it as this ‘yucky, smelly, slimy’ thing to genuinely considering marine science as a career – especially after they’ve interacted with real scientists.”

Tūhoe, 16, adds, “We are trying to save Porirua harbour [and coastal areas] by putting the seaweed we grow back into it to help clean it up. In the olden days, we could dive and surf there all the time, but now it’s too polluted to swim in.”

“I still surf there and I can really smell the pollution when it’s low tide, especially after there’s been heaps of rain,” says Jack, 17. “I think it’s great that we can make a difference.”

Gallery