Evangelism and Freedom of Choice

Leonard Monk Isitt 1855 – 1937

The recent Court findings in relation to the Gloriavale Community bring into focus once again the blurred line between choice and duty as it applies to living out one’s Christian beliefs in daily living. I suspect many New Zealanders will regard the judgment as a vindication of our freedom to choose how we express our beliefs. It is hard not to see in that West Coast Community’s ordering an extraordinarily high degree of hierarchical control - from the names each member is given at birth to their unquestioning obligation to do their duties in the daily organization of that close-knit society. It remains to be seen how its leadership responds in its appeal but it is unlikely that they will win the hearts and minds of a majority within Aotearoa in favour of their strict code of behaviour.

Evangelism is centered, as its name implies, on good news. Throughout its 2000-year history the Christian Church has tended towards separation from the wider community. To some, even in its mildest form, ‘orthodox’ Sunday-morning worship still represents that ‘coming apart’ from our neighbours. The time and the place of such worship is witness to a different set of values. Just how far we are prepared to go in our weekday living to maintain that difference is a matter of choice, rather than of rule, though that certainly was once the case and is clearly at the very heart of the Gloriavale ethos.

One essential area of community and social life is related to the education of the young. Until relatively recently, in historical terms, education in the Western world was controlled by the Christian Church. The very idea of a secular education would have been almost beyond the comprehension of the European mindset – that which came to this country within the last two centuries. The idea that such people could learn from the nurturing traditions of the tangata whenua was, for them, unthinkable. And even to create an education system, in this ‘new world of Aotearoa’ which did not reflect that basic Christian premise took decades to achieve. It was not until 1870 that an Education Act was passed that enshrined the principle of secular education.

The Christian churches did not give up their commitment to religious training of the young even then. The ‘religion-in-schools’ movement was widespread. Some of the larger Christian churches, of course, had created their own Church School system – even the Methodists did so, and Wesley College, Paerata, is a reminder of 180 years of such Methodist commitment to an education that gave expression to an understanding of the Christian way of life.

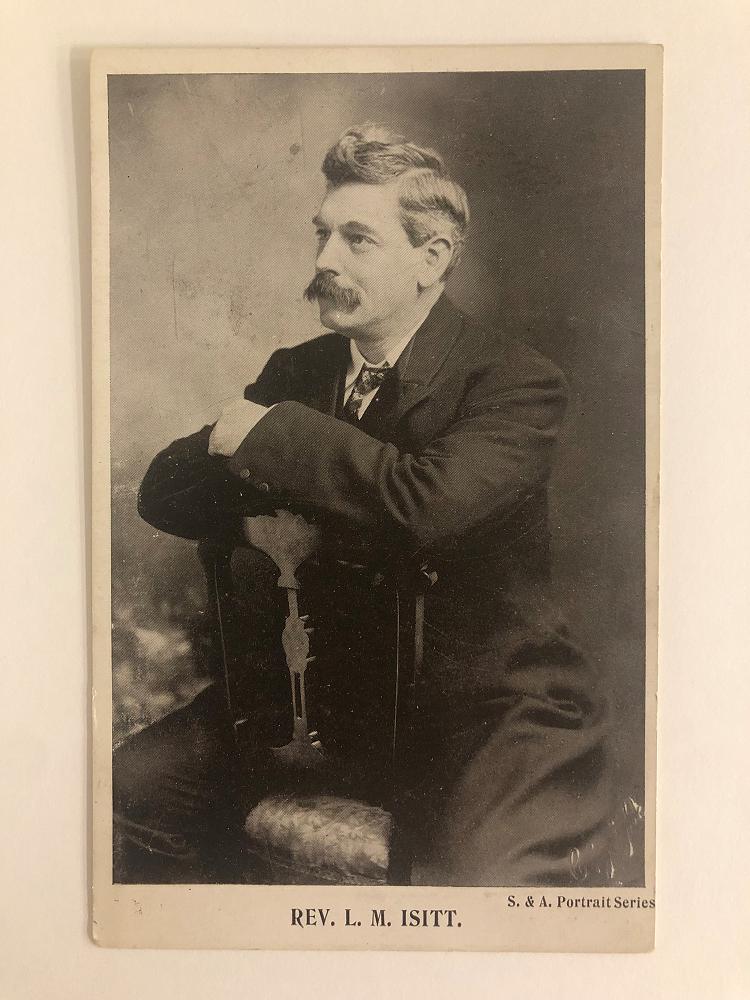

This article recalls one former Methodist minister who gave so much of his time and energy to keeping ‘religion’ at the heart of the New Zealand education curriculum. Exactly 100 years ago, in September 1923, Leonard Monk Isitt introduced a measure into the Parliamentary agenda entitled ‘Religion in Schools’. The Methodist Times described the intentions of the Bill as providing for religious exercises of a “simple character”. There was to be no instruction of a dogmatic or denominational nature. The Lord’s Prayer would be recited and a hymn would be sung, from a manual to be put together by the Education Department. The teacher would offer a Bible lesson, also from an approved manual. There was to be no compulsion to attend this instruction which would be offered every day. That the newspaper should describe it as a “splendidly suitable” Bill underlines how far the older view of the Christian religion still prevailed.

The promoter of the legislation, L.M. Isitt, with his brother Frank, came to this country in the 1870s from a thoroughly English Methodist family background. While Frank spent most of his life in regular ministry, Leonard had about 10 years in circuits, ranging from Lawrence to Tuakau. His commitment to the aims of the Prohibition Movement, including the editorship of the NZ Alliance’s national newspaper, was absolute. One gains the impression that Leonard preferred a national platform to a local pulpit. While engaged in the work of the NZ Alliance, he retained his ministerial status but in 1908 he retired from ministry to set up in business as a bookseller and three years later he entered Parliament as an Independent member for Christchurch North. He was not a ‘single issue’ politician in Allan Davidson’s view and he certainly was not a religious bigot. But he was committed to moral reform in its variety.

A lesson might be drawn from these two very different examples of the Christian religion in action. Gloriavale, it seems to this writer, has chosen to withdraw from the world for which it doubtless prays. Leonard Isitt represents that ever-present wish among committed Christians to be out and about – especially seeking change through influencing those who direct the affairs of society. The extraordinary developments in communications over recent decades brings the world, and the ability to speak with it, within the reach of literally anyone. Jesus went out into his world to change it. We can do the same and we don’t need to ask permission to do so.