A Russian Connection

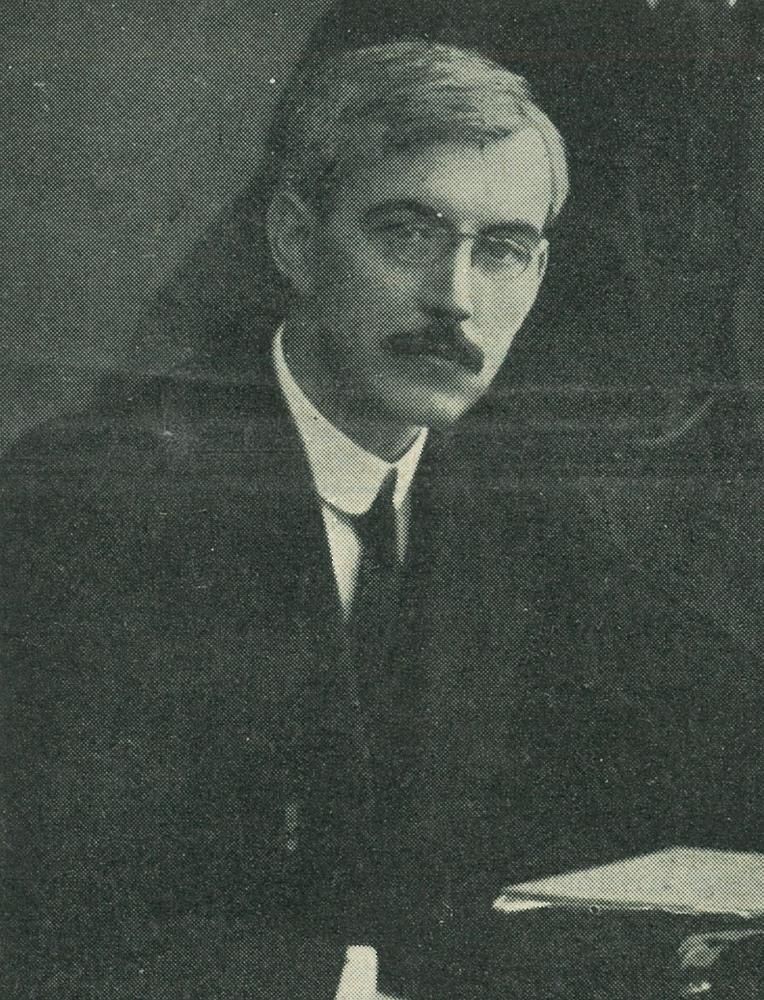

Harold Whitmore Williams (1876 – 1928) & his wife Ariadna Vladimirovna Tyrkova (1869 – 1962)

In these fraught times, with indiscriminate slaughter and the insatiable lust for power of one man gripping our attention, it is timely to return to Harold Williams, a New Zealand Methodist parsonage kid whom I have written about before. Just 15 years ago his life – which ended too soon in 1928 - was the subject of a second biography, this time by Charlotte Alston. Her title is an arresting one: Russia’s Greatest Enemy? Harold Williams and the Russian Revolution. What could he have done to warrant such a label?

When writing of him earlier, my focus had been almost exclusively on Harold himself and it is worth being reminded of the important facts in his relatively short but very notable career. Now I want to talk about his wife in more detail because she was a primary influence in forming his attitudes toward the developing Russian state in the 1920s. The revolutionary changes that took place then are still being worked out.

Harold was born in Auckland in 1876, the son of William James Williams, one of the leading ministers of his generation. Harold was educated in Christchurch and Timaru and did his undergraduate studies at Auckland University College. His time in the ministry was limited to a holiday supply at Feilding and probation at Papanui and Inglewood. His health led to a year’s rest and then a brief supply ministry at Dargaville. By this stage it was obvious his skills and his vocation were in the study of language and he spent time at both Berlin and Munich where he gained his doctorate in 1903. He maintained a passion for language throughout his life and he gained an extraordinary reputation for his multilingualism. It was said that when he, as a newspaper correspondent, attended the International Peace Conference at Locarno in the 1920s, he was able to engage in fluent conversation with every delegate in their own tongue.

He was a newspaper correspondent for the Times, the Manchester Guardian, the Morning Post and the Daily Chronicle from 1905 until about 1920. From that time he was the Foreign Editor of the Times when that London newspaper was a world leader in coverage and authority. His death came as a shock to his friends and to the journalistic world as a whole. He was noted for his reserve but equally for his friendship. He was a source of pride to his family but also to his Church which reported his progress and endorsed his ethical standards.

Harold’s wife, Ariadna Vladimirovna Tyrkova, born in 1869, was the daughter of a landowner from northern Russia. She studied in St Petersburg in the early 1900s and became active among liberal opposition groups. She moved to Germany, where in 1904 she met Williams. Together they moved to Paris but at the end of the year Williams was sent to St Petersburg by the Morning Post. She was shortly afterwards able to follow him, returning to Russia under a general amnesty. She helped found the Constitutional Democratic party (also known as the Kadet Party) and in 1906 became a member of its Central Committee. In 1906 she married Harold and in the same year joined the All-Russian Union for Women’s Equality, becoming a leading campaigner for equal rights for women. The Constitutional Democratic party added women's suffrage to its platform.

In 1911 the family was briefly embroiled in controversy when Harold was accused of espionage, supposedly the outcome of Russian secret police machinations. In March 1917, immediately after the February Revolution, Tyrkova-Williams was elected a member of the Petrograd Committee of the Kadet party. She coordinated party publications in Petrograd (formerly St Petersburg) and in the summer of 1917 was elected to the Petrograd Duma, where she led the Constitutional Democratic faction. In August she became a member of the Democratic Conference and in September was elected to the Pre-Parliament. In the spring of 1918, she emigrated to Britain and in 1919 published an account of the first year of the Russian revolution.

In London, she became a founder of the London-based Russian Liberation Committee, edited its publications and raised money for Russian orphans. The account of her particular involvements - her commitment to constitutional change and to women’s suffrage - aligned her with what was happening in the world influenced by Western European culture and politics. It is hard to imagine how radical her platform was in Tsarist Russia and equally, how out of line she would necessarily become with Bolshevik totalitarianism. Her passion must have profoundly influenced her husband, himself a person of political influence but she was deeply versed in, and committed to, her own view of Russia’s future. The events of these past few weeks underline just how little the exercise of power has changed in Russia in 100 years!

Together with Harold she wrote a novel, Hosts of Darkness, then about the time of Harold’s death a biography of Alexander Pushkin. In 1935 she wrote Cheerful Giver about her late husband. After WW2, in March 1951, she migrated to the USA and died on 12 January 1962 in Washington DC.