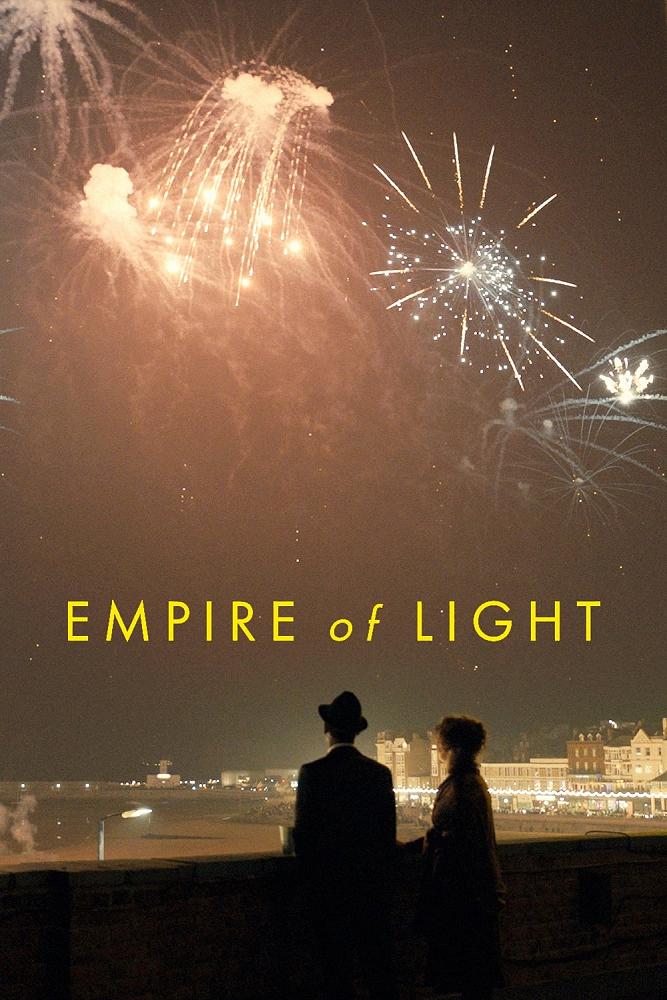

Empire of Light

The film Empire of Light is intense.

Actor Olivia Colman as Hilary is superb. The raw power of her emotional breakdown is extraordinary, as are the shifts in sound between the door to Hilary’s flat being forced open and the silence of success. With actor Micheal Ward as Stephen, we witness the devastation that racism, sexism and mental illness can wreak in everyday lives.

The intensity is magnified by the backdrop of time and location. The year is 1981, and race riots shatter the façade of Margaret Thatcher’s England. Casual racism spirals into violence as Stephen is brutally beaten for the colour of his skin.

The location for the senseless beating is the foyer of Empire, a movie theatre located on a British waterfront. Movies about movies are a well-worn cinematic trope. Despite the cliches, the opening scenes as the art deco movie theatre is brought to life for the evening shows, are a gorgeous call to life.

Empire of Light is directed by Sam Mendes, knighted for services to film, beginning with American Beauty in 2002. In Empire of Light, Mendes is both director and scriptwriter and he works hard to squeeze a range of predictable metaphors from an ageing movie theatre. Disused rooms are places of potential. Birds with broken wings learn to fly. None of the metaphors seems as poignant as the plastic bags in American Beauty, for which Mendes gained his first, of four, Academy awards.

In writing the script for Empire of Light, Mendes drew on his mother’s mental health challenges. Although not autobiographical, Mendes has shared how raising his children caused him to reflect on his upbringing. While fictional, the emotional intensity of Empire of Light invites needed conversations about pastoral care and theologies of shame.

In Hilary’s flat, as she rages with pain, Stephen provides a pastoral model of presence. He needs no skills to fix or solve. Instead, Stephen offers the gift of a silent presence and listening ear. To use theological language, as Stephen bears witness to Hilary’s story, he honours her emotions and holds her pain.

The movie spotlights shame. “Did I humiliate myself?” Hilary later asks Stephen. “It was intense,” comes Stephen’s kind reply. The impact of shame on human experience comes early in Scripture. In Genesis 3, Adam and Eve hide from God, ashamed of their nakedness.

God responds to the human experience of shame with a listening ear and the practical offer of clothes. Like Stephen, there is kindness.

While Mendes spends most of Empire of Light composing an ode to cinema, the ending offers a surprising twist. Cinematic metaphors are shed for nature metaphors.

Stephen and Hilary part, not at the Empire, but in a park. Hilary gifts Stephen a book of poetry and Stephen reads Philip Larkin’s poem, The Trees (The Complete Poems of Philip Larkin (2012).

Last year is dead, they seem to say,

Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.

Empire of Light offers a freshness in which the kindness of human presence transforms the intensity of human pain.

Rev Dr Steve Taylor is the author of "First Expressions" (2019) and writes widely in theology and popular culture, including regularly at www.emergentkiwi.org.nz.