Honest to God

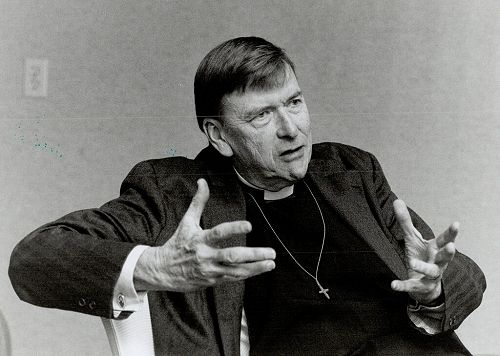

John Shelby Spong: A Champion for Change in the Church

There are those who think nothing in the church must change and there are those who know it has to. American Episcopal Bishop John Shelby Spong, who died on 12 September aged 90, was emphatically one of the latter.

Many New Zealanders know that well. He visited four times between 1991 and 2001, speaking to appreciative audiences and stirring hostility among those who prefer not to be disturbed by new thinking.

Spong has long been in the forefront of such thinking but he didn’t begin that way. Early influences in his North Carolina home were Presbyterian fundamentalism and high church Anglican fundamentalism, and he grew up absorbing all the prejudices of his time and place about blacks, women and homosexuals.

Driven, however, by a deepening understanding of Christian faith, an uncompromising intellectual rigour and a discipline of study from 6am to 8am every day, he became over time a champion of racial justice, women’s equality and homosexual liberation – especially in the church.

Spong was acutely conscious of the huge expansion of human knowledge in recent times and the need for Christianity to take account of that if it is to be relevant to men and women of the 21st century. This led him to probe beyond interpretations cemented into traditional church life and find a way of understanding scripture, for example, that is in sync with the world we actually live in.

His motivation was to go deeper into the heart of the tradition in order to identify and affirm more appropriately its core. He was willing to explore beyond creedal formulas about God, the work of Christ, the church, prayer, worship: if they don’t connect, they are not much use. Biblical literalism appalled him.

A living religion is in a dialogue between spiritual insight and new knowledge, he said. It is therefore always in flux and always evolving. Arrest the process and it slowly dies: “The heart cannot worship what the mind rejects”.

Spong was prepared to follow the evidence wherever it led. He abhorred dishonesty and anything that stood in the way of expansion of life. A key to this was “Christpower”, a term that summed up for him the sense of love, forgiveness and expanded being, associated originally with Jesus. Christpower offers the ability to change, to grow and to embrace the radical insecurity of life as free, whole and mature persons, which is the essence of faith.

A major contribution was Spong’s exposition of the Jewishness of Jesus’ life, reflected also in the gospels and Paul’s letters. Early in his career it spurred him to reach out in dialogue with the local Jewish community. Breaking down barriers became a central theme.

The responsibility he felt as a leader – he was Bishop of Newark, New Jersey, from 1979 to 2000 – prompted him to share the insights of his studies more widely through a succession of books. He wrote 26 in all, introducing his theological hot potatoes with “A bishop rethinks the meaning of Scripture”, “A bishop rethinks the Virgin Birth and the treatment of women by a male-dominated church”, and “A bishop rethinks human sexuality”.

Spong saw himself as struggling for a Christianity of integrity, love and equality. While many responded with warmth and gratitude, antagonism from the church’s conservative wing gradually led to his disillusionment with its institutional workings.

“The church of my dreams and visions,” he wrote, “the church I had glimpsed periodically, the church I loved, was being drowned in a sea of dated theological irrelevancy undergirded by biblical ignorance.”

In his later years Spong’s prime audience became those who were open to a new Christianity for a new world, an audience of “church hangers-on and dropouts, atheists and agnostics, anyone on a spiritual journey who is seeking meaning, integrity and God”.

Always he knew how to ask the right faith questions. Inevitably, this stirred controversy. Anger: “Burning you at the stake would be too kind.” And appreciation: “You have made it possible for me to remain in the church.”

I honour Spong not for having all the answers for a church in transition but for his commitment to spurring it on that journey, mindful of what it’s really about: “True religion is, at its core, nothing more or less than a call to live fully, to love wastefully and to be all that we can be. That is finally where life’s meaning is found.”

The fact that secular audiences could hear him gladly but many in the churches could not is worth reflecting on.

Gallery