Grasp Their Hands In Union

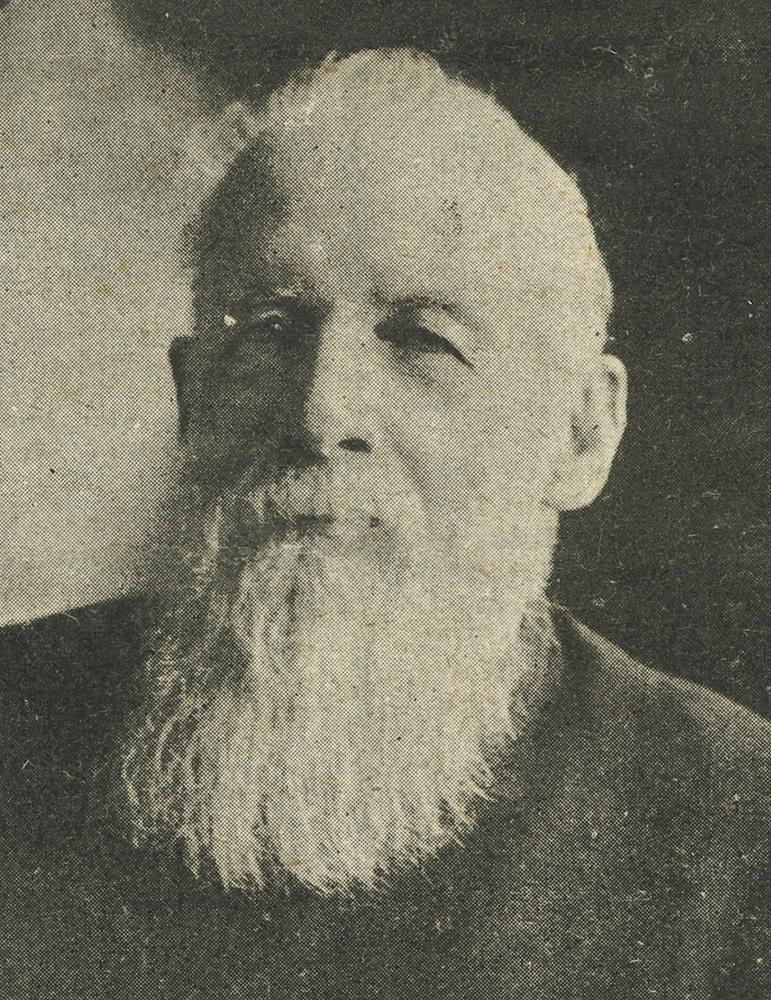

Jabez Bunting Watkin was born in Tonga in 1837, grew up as a small child at Waikouaiti and was educated at the new Wesleyan school in Auckland. Afterwards he lived with his brother James in Wellington, then in Christchurch where for four years he was a local preacher. He moved to Australia and in 1863 entered the ministry within the Queensland Conference. In 1866 he went to Fiji and finally returned to Tonga where he spent the rest of his long ministry.

He became part of the breakaway Methodist ‘Free Church of Tonga’ and was its President from 1885 until 1924, a year before his death. He remained, however utterly committed to its Wesleyan principles. The story of that disruption in Tonga is a complicated one – and to a considerable degree was the result of a falling-out between two English Methodist ministers – James Moulton and Shirley Baker. The latter became premier under the king, Tupou I, and played a prominent role in the pursuit of independence and freedom from missionary intervention. This led to the total break from the Wesleyan Methodist Conference of New South Wales.

Baker’s activities had brought him into conflict with the British colonial authorities. He suffered a serious fall from grace and was forced to leave the ministry, and the country. In this writer’s view, New Zealand Methodism watched all this with real concern, but passively. Since Tonga was associated with the NSW Conference they could, strictly speaking, do very little. Almost certainly their sympathies were with the Free Church, and behind-the-scenes contact must have been maintained for decades between New Zealand and Tongan Methodists.

It seems that one of those who did this was M A Rugby Pratt, in the early 1920s a senior circuit minister and writer. Later in that decade he became Connexional Secretary - a post he held for nearly 20 years, longer than any other in the history of NZ Methodism. But at this moment he was a ‘free agent’.

In 1922 New Zealand Methodism became responsible for its own mission-field – the Solomon Islands – and established its own Overseas Mission Department. Until that time New Zealand Methodists who wanted to serve in the South Pacific transferred their membership to the NSW Conference. Now there was an opportunity for the Connexion here to act independently and memories of the time when there were very close links with Tonga must have been aroused.

The October 1922 edition of the New Zealand Methodist Times has a leading article on the nature of Pratt’s visit to Tonga. It is couched in language that would match any used by the most careful diplomat caught up in some international dispute. This was an ‘unofficial’ visit – but quite clearly it was a visit made with the approval of the leadership of the Connexion. It was a ‘good will’ visit, to “our brethren of the Free Church of Tonga, bound to us by ties of Methodist ancestry and heritage.”

Words like these aren’t used without there being an intention to restore relationships broken for too long. The phrase ‘ecclesiastical isolation’ is used. The editor (possibly Percy Paris) expressed the hope that, “One day it may be we shall grasp their hands in union.” Altogether there is a vision of reconciliation – at least in an institutional sense. At a personal level Pratt and J B Watkin may well have been friends already – and there was never a suggestion that friendship between Tongan and New Zealand Methodists was somehow uneasy or qualified.

The personal friendship was real but there needed something done to establish more formal church to church links. These weren’t easy times for Methodism in Tonga, and the old division ran deep. J B Watkin, as President of the Free Church of Tonga, always exercised a mediating role in that he represented, partly through his being the son of a Wesleyan missionary in that country in 1830, a symbol of continuity with Wesleyan Methodist beginnings in England.

But JB also represented the people of Tonga who recognised the royal family as theirs. He in fact crowned Queen Salote at her coronation in 1918. He had been President of that Church for a very long time and was close to the king throughout the later years of his reign – as his father had been at its beginning. His ministry in a way personified a very deep and lasting connection between New Zealand and Tongan Methodism.

All this may have been in Rugby Pratt’s mind when he made his visit. That same shared history matters more than ever in the changing world of the 2020s, a century after this journey of reconciliation.