Victoria the Good: The Passing of a Queen

In a 19th century communion roll from Crathie Church near Balmoral in Scotland, one of the names listed is given simply as “Victoria”, with her occupation noted as “Queen”. Beside the following dates are crosses marking her attendance at Communion.

After the death of her husband, Prince Albert in 1873, Queen Victoria spent increasing amounts of time in Scotland. Her diary records that she appreciated the “touching and beautiful simplicity” of the services at Crathie. Following her death on 22 January 1901, an article reprinted in The Outlook, the main New Zealand Presbyterian newspaper, attempted to claim her saying that “it may be hazarded that the forms of service in which she found most satisfaction were those of the Presbyterian Church.”

As well as being Head of the Church of England, she was also the official head of the Church of Scotland and when she died in 1901 after reigning for 63 years, she was the only monarch that most of her subjects, including those in New Zealand, had ever known. Rev John McKenzie of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in Christchurch noted in his sermon on the Sunday following the Queen’s death: “Her long reign had caused her to be regarded by most as a part of the fixed order of things, and even her great age had not caused people to picture what the world would be without her.”

How did New Zealand Presbyterians react to the passing of the Queen? As with the passing of Queen Elizabeth II more than 120 years later, there was an outpouring of collective public grief. Rev John McKenzie spoke of the “personal note in every expression of grief” along with the “universal nature of the Empire’s sorrow”.

Most churches across the country held memorial services on 27 January, the first Sunday following the Queen’s death. The interior of many churches, including the pulpit, was swathed in black and worshippers wore mourning dress. Many preachers took as their theme, ‘Victoria the Good’ and services concluded with the playing of the Dead March from Saul by Handel. Invitations to these special services were extended especially to the very old and the very young. St Andrew’s Church in Allen Road, Auckland made the point that ‘Old Colonists’ were especially invited, whilst in Dunedin the Combined Sunday School Unions held memorial services for children across two venues - the Agricultural Hall and Knox Church - because of the large numbers expected to attend. Invitations to this event were also issued to older children and youth from the Bible Class and Christian Endeavour movements.

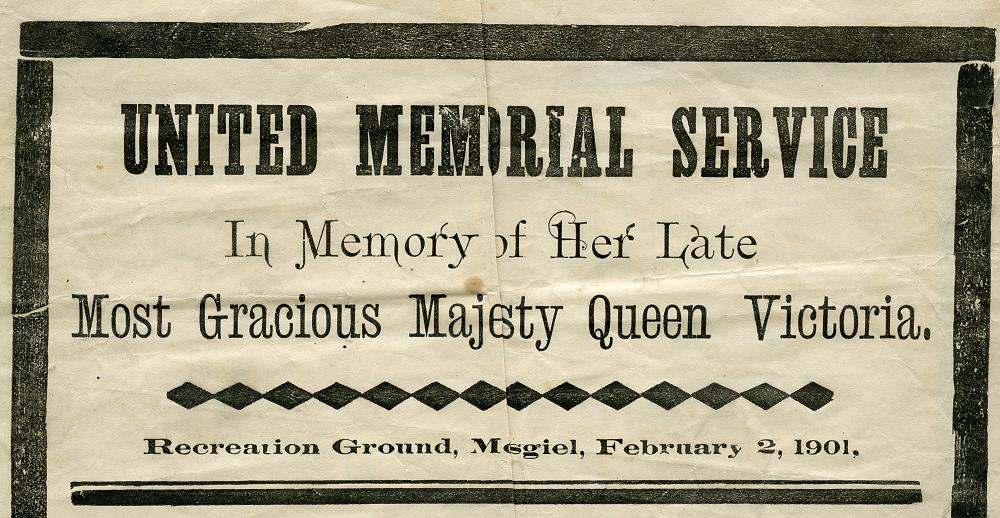

Many communities also held combined ecumenical services. Several thousand people attended a service in Cathedral Square, Christchurch. Events were also held in smaller centres, such as Mosgiel, Otago where a ‘United Memorial Service’ was held on the Recreation Ground on 2 February, the day of the Queen’s funeral service in London. The service included contributions from the local Presbyterian, Methodist and Salvation Army ministers and the singing of many hymns.

More than half of the 2 February edition of The Outlook was given over to articles about the late Queen. They praised the life of ‘Victoria the Good,’ extolling her truthfulness and unselfishness, her dedication to peace and her devotion to duty. Much was made of her role as a mother and her personal religious practice. A number of articles gave anecdotes and stories of encounters with the Queen while others told readers of her favourite books and hymns. The collective mood of the country was perhaps best summed up by the editor who wrote, “There come experiences too great for speech.”