The role of the model

Making has a key role in design education within the context of the Architecture and Fashion design studios.

In design education, the final design prototype is intended to be a close facsimile of a final professional design, whether that is in architecture or fashion. The materials, the processes, and the delivery are all as similar as possible to how the design would appear in a professional space, editorial image or competition. But there are important differences between disciplines that are seldom discussed. Stella Lange (Fashion) and Col Fay (Architectural Design) have begun a conversation comparing the very different approaches to the use of the prototype/model in education in their respective design disciplines.

Fashion students can make a series of prototypes using different fabrics and techniques, to see how garments hang for example. In Fashion design education the final prototype, known as the sample garment, is as close in scale, materiality, and assembly as it can be to a professional outcome but it is still a model of what might be produced commercially.

In Architectural Studies the final design prototype is simulated, and executed in materials, scales and processes that are very different to the intended built outcome. Architectural students use the model differently, not to emulate reality but to bind their design to a physical reality, enabling the built form to be examined in a representation of its geographical context.

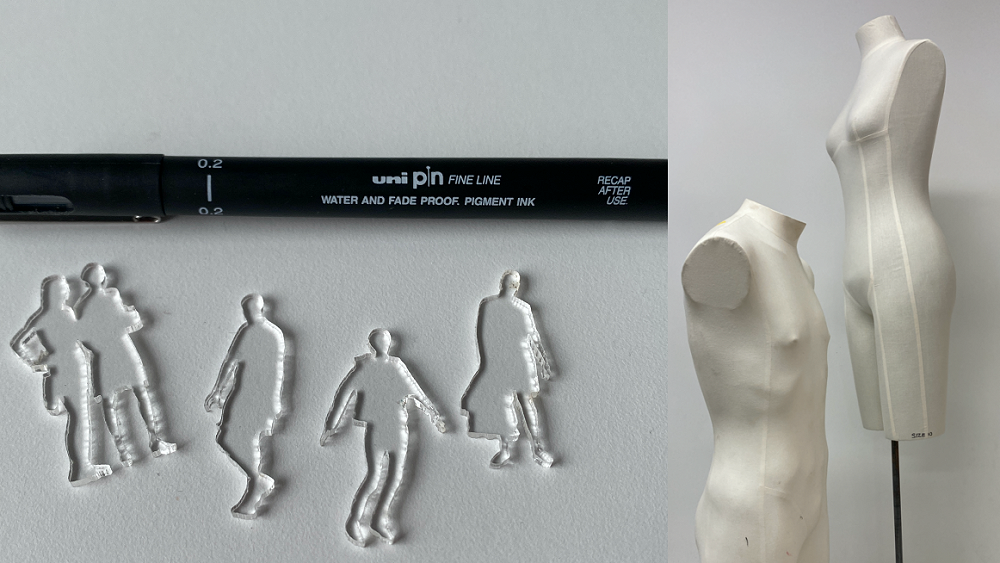

Both Fashion and Architecture use the human body in modelling, but while fashion models are 1:1 with a life size mannequin, architecture necessarily uses miniaturisation with two dimensional silhouettes of people for scale. Design education aims to replicate the practice of the profession, including through experimental and experiential design. The purpose of the model is to help concretise ideas as part of their development, and the model is both an object in itself and a representation of something else. Stella and Col agree that physical making develops a valuable relationship between brain and hand.