From the Deputy Rector

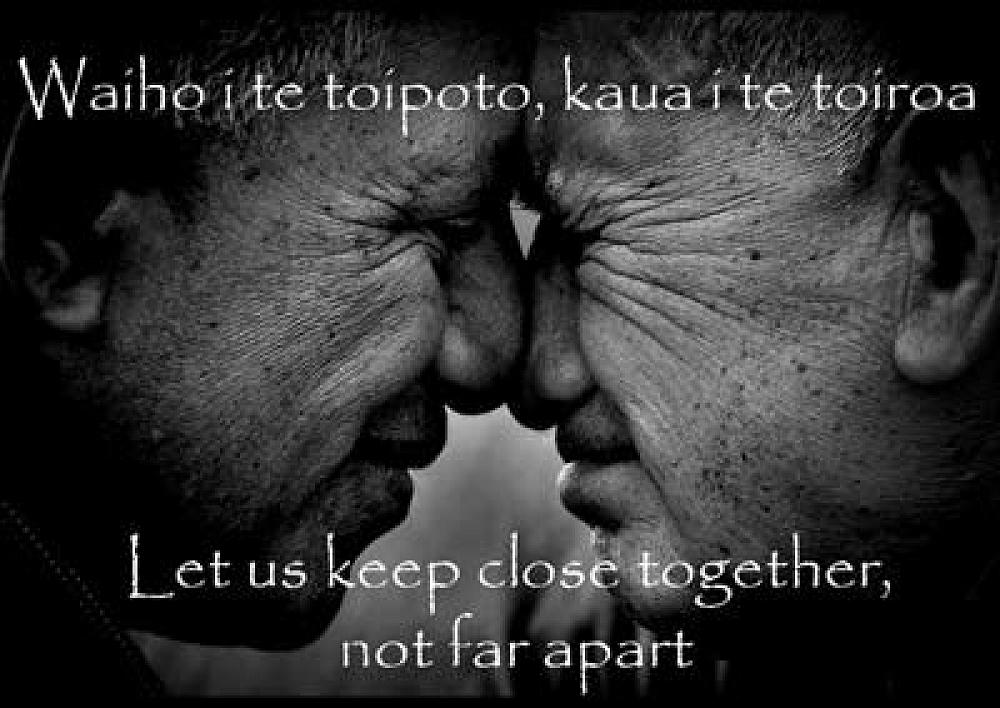

While the focus of te wiki o te reo Māori (Māori Language Week) is on the promotion of te reo Māori, it also prompts us to consider the broader picture of our history in both Te Papaioea and Aotearoa.

Nestled in the heart of Te Papaioea (Palmerston North) is Te Marae o Hine – The Courtyard of the Daughter of Peace, or as it is more commonly known to those outside of Rangitāne, the Square. The gift of this land and name by Māori in 1878 was a symbol of the desire to bring Māori and Pākehā together peacefully as well as recognition of the need to secure a space for Māori customs as the number of European settlers rapidly grew.

A statue of Rangitāne rangatira (chieftain) Te Peeti Te Awe Awe, who was instrumental in both the peaceful relations between Māori and Pākehā in the Manawatū and the European settlement and development of the area, stands prominently in Te Marae o Hine. His ōhākī, or parting words, are inscribed on the pedestal:

"Kua kaupapa i au te aroha mā koutou e whakaoti" - I have laid the foundation of friendship for you to bring to completion.

It is timely for us all to consider the extent to which the foundation of friendship Te Peeti Te Awe Awe spoke of has been built upon and how much more is yet to be 'constructed'.

Yes, we are all New Zealanders and yes, we are a multicultural country whose inhabitants come from all around the world and whose cultures, traditions and languages contribute to the diverse society we live in today. However, the special place that Māori as tangata whenua hold, that Rangitāne as mana whenua have in our region and that tikanga Māori and te reo Māori have must be acknowledged. If we are to consider ourselves New Zealanders, then we must protect and nurture the very essence of what makes us unique.

What Do We Want For Our Children?

When parents of young people of all ages are asked what they want for them a common - and completely understandable - refrain is that they want them to be happy. However, as we contemplate this idea it becomes a little more complex than we might initially think.

Modern philosophers have three broad approaches to answering the question "what is happiness?" The first is that happiness is the opposite of depression. If we are happy we are experiencing a positive 'upbeat' attitude. The second is hedonism, a school of thought that argues people actively seek out pleasure and do all they can to avoid pain. To judge a happy life one would consider the total proportion of our lives we spend enjoying ourselves.

While, at first glance, these definitions sound very appealing, they do not reflect the reality of our day to day lives. Do we really want our children to experience pleasure at all times? Struggle and failure are things that we all experience from time to time, and in 2020 perhaps more so than usual. Struggling with something, be it an assessment, a relationship, conflict at school or work, or failing in any of these areas is not enjoyable; it does not make us happy. However, we learn much from these experiences, perhaps much more than we do when we succeed in something without having to overcome obstacles and without having to make a genuine effort.

If we accept that struggle and failure are important parts of our lives and that we learn from these experiences, then perhaps we need a more nuanced understanding of what ultimately makes us, and our children, happy.

The third approach to happiness is one that is built on the philosophy espoused by Aristotle more than 2,300 years ago. He proposed that happiness came from a sense of fulfilment and satisfaction about our conduct, our interactions and our relationships. An element of activity - doing things that challenge us and we enjoy - and having direction and goals in our lives also lead to happiness.

Edith Hall, Professor of Classics at King's College in London, noted that "Aristotle believed that if you train yourself to be good, by working on your virtues and controlling your vices, you will discover that a happy state of mind comes from habitually doing the right thing." Philosopher Will Durant summed this up succinctly, in a well-known quote that is frequently misattributed to Aristotle:

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” - Will Durant in 'the Story of Philosophy'

Two important points are evident. The first is that who we are and who we are becoming - our character - is malleable. The second is that we can influence 'who' we become and also the character of those around us. Encouraging and rewarding virtuous actions - the good decisions our young men make at home, school and in the community, helps to shape their character.

Whakawhānaungatanga, the Māori concept of developing purposeful connections and relationships of interdependence, encapsulates and builds on this idea. The people we choose to surround ourselves with do influence our personality and behaviour - our character. Therefore, we should choose carefully. And, we should encourage the young people in our lives to likewise choose carefully.

Community and relationships are other concepts stressed in Aristotle's theories about happiness. He believed that we flourish when we live peacefully in association with others and engage in reciprocal good deeds. Aristotle suggested the placing of shrines in public places as a reminder to people to 'return a kindness; for that is a special characteristic of grace, since it is a duty not only to repay a service done to you, but at another time to take the initiative in doing a service yourself.'

We encourage our young men to provide service to their community. In doing so they strengthen their links to their community, whether it be people they know who are the direct beneficiaries of their service, or whether it be an altruistic act for the benefit of a stranger. Such acts build our character as individuals and help to build the positive communities and societies we want our children to grow up in.

Community and relationships are important aspects of Māori society. Kotahitanga is the concept of togetherness - developing relationships, forming community, working together. Manakitanga means to extend aroha (love and compassion) to others. It is found in acts such as helping a loved one, encouraging one another or even supporting a complete stranger. Manaakitanga is one of the most important concepts to Māori people as it secures the strength of whānau (families) and communities. Developing kotahitanga and manaakitanga will strengthen the character of individuals and society as a whole.

Jamil Zaki, an associate professor of psychology at Stanford University and author of The War for Kindness: Building Empathy in a Fractured World is another to recognise the importance of our relationships:

"Remember that the people around you are part of your environment. Like the air you breathe and the food you eat, their opinions, attitudes, and actions work their way into you—so try to keep the healthiest company you can. Second, you should remember that you are someone else’s environment, and might have more power to affect them than you realise."

Hall posits that, according to Aristotle, "the ultimate goal of human life is, simply, happiness, which means finding a purpose in order to realise your potential and working on your behaviour to become the best version of yourself." This definition of happiness sounds like one that will benefit our children and ourselves regardless of the circumstances that we find ourselves in and one that is much more applicable to the reality of life's 'ups and downs'.

Many of Aristotle's sentiments are shared by Eric Barker, author of the New York Times bestseller 'Barking Up the Wrong Tree: The Surprising Science Behind Why Everything You Know About Success is (Mostly) Wrong' In this article Barker shares his ideas about what gives our lives meaning: 'The Fun Way to a Meaningful Life'.

Character Education

One's character is a 'work in progress'. The unique experiences that we all have mean that 'who we are' at any given time is different from who we were in the past and who we will be in the future. While there are many events that we have little control over, we can do much to influence who the young people in our care are becoming.

One way is to look for opportunities to engage them in discussion about morally and ethically challenging topics. The upcoming election and referenda provide such an opportunity. Have you asked your son about his thoughts on the End of Life Choice Act and the Cannabis Legalisation and Control Bill? There will rightly be a range of opinions on these topics and they provide a rich background for debate and discussion - not an opportunity to simply prove someone right and others wrong - but an opportunity for young men to be challenged to reflect on why they hold certain beliefs and to understand other's perspectives.

Likewise, a recent media article told the story of two burglars in France who broke into a house and stole a laptop. Upon discovering a cache of child pornography on the device they took it to the Police rather than sell it as they had intended. How virtuous was their act? Does their 'right' action in going to the Police make up for the initial 'wrong' action of theft? Such stories provide a fertile context for discussions that will help your son to develop his sense of right and wrong and his own practical understanding of the application of his morals and values.

To Develop Educated Men of Outstanding Character

Hai Whakapakari i Ngā Tamatāne Kia Purapura Tuawhiti