Profile: Anthony Connell

From the safety of our homes in New Zealand, it is easy to feel like the war happening in Ukraine is another world away. But for Anthony Connell (1971-1975), life currently revolves around the war effort and helping the Ukrainian people...

Anthony, can you tell us about the job you are doing in Ukraine?

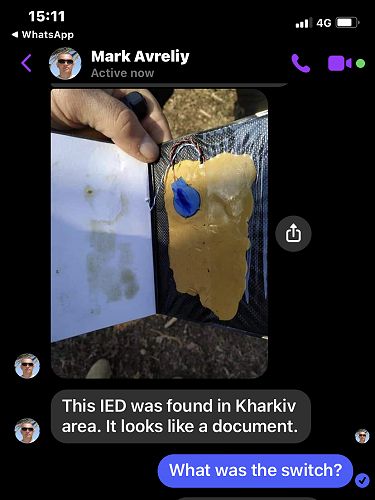

I work for a Swiss based Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) called Fondation suisse de deminage (FSD). FSD has been operating in Ukraine since 2015. I arrived in Ukraine in 2016, initially as the Operations Manager but in 2018, I took over as the Country Director. Our task in Ukraine is to carry out humanitarian mine and unexploded ordnance (UXO) clearance which includes an initial survey of potentially contaminated areas and mine risk education. Our work is directed through the National Mine Action Authority (NMAA) in which the areas we work and the priority of tasks are allocated. When the conflict started in 2014 our work was concentrated in the east of Ukraine – in an area known as the Donbass. However, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, we moved to the central north of Ukraine – an area that was badly contaminated with UXO during the initial stages of the Russian invasion.

My job is to control all aspects of the work, not just the operational side of things but also the finance, administration, and logistics plus conduct liaison with the national authorities including the NMAA and the Ministry of Defence. I also am responsible for maintaining liaison with the representatives of our donors through the in-country embassies.

Where do you live/work and how many people do you work with?

I live and work (at the moment) in a city called Chernihiv, some 130 km north of Kyiv (the capital of Ukraine). Chernihiv is situated approximately 50 km from the Russian border. Chernihiv was attacked by the Russians in the early days of the invasion but was never captured. Significant damage was done to the northern and western suburbs by Russian artillery and rocket strikes. I have a team of nine other international staff and 145 national staff.

How did you come to be working in your current role?

When I left St Bede's at the end of 1975 I joined the Army and had a very rewarding and satisfying military career for 24 years.

I became involved in mine clearance when I left the Army in 1999. I worked initially in Iraq where I worked for a commercial demining company and I have wandered around various mine-affected countries ever since. I have worked in Iraq, Albania (twice), Sudan and South Sudan, Angola, Syria, Somaliland, Colombia, and Ukraine.

I had finished working in Syria and was waiting for a visa to enter Yemen. However, after three months, it was obvious I was not going to be issued a visa, so I accepted an offer from FSD to move to Ukraine in October 2016. The initial appointment was as the Operations Manager with the specific task of recruiting and training two Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) teams. The Country Director resigned and I was asked to take over – which I did.

What does an average day look like for you at work? What does an average day look like for you on your days off?

Every Monday, my key staff (Operations Manager, Logistics/Administration Officer, Finance Officer and my deputy) gather for a coordination meeting to discuss the planned activities of the next month - in outline and then the activities of the next 14 days in detail. The key issues that are discussed are :

The security situation and what indications do we have about any threats to our staff

New areas of UXO contamination that may need urgent attention

Any issues regarding staff, equipment, finance, or logistics

Future plans including the conduct of reconnaissance teams looking at new areas

Any assistance requests we may have received from the NMAA or MoD

Any other general matters.

The rest of the week revolves around following up on any issues, writing proposals for new or additional funding, writing reports for donors visiting teams in the field, and visiting national authorities and embassies in Kyiv.

Each day starts around 0745 & finishes around 1800 – if I am lucky. Inevitably there is work that I do back at my flat after hours.

Weekends are generally free, in as much as I don’t go to the office. But it is a time to catch up on paperwork. Sightseeing is not an option as there is a fuel shortage. Once every 6 weeks or so I might go to Kyiv for a weekend & leave my laptop behind. But the phone still rings.

How has your daily life changed since the war began? What is it like living in a country affected by war?

Daily life has changed since the invasion. There are frequent air raid warnings at all hours of the day and night. This becomes quite tiresome when you are woken at 0230 in the morning from a deep sleep. As I said earlier there is a fuel shortage so any necessary travel is limited to the absolute minimum.

The people of Ukraine are pretty robust – they are not taking the invasion lightly. They are fully prepared to defend their country to the last inch. They are also very resilient. The damage created by the Russians around Chernihiv is being cleared by the inhabitants themselves. The Government is concentrating its efforts on fighting the Russians, so the population is just getting on with the clean-up themselves.

The cost of living has risen dramatically. In the liberated areas, life has returned to normal – as much as it can. There is no shortage of food, electricity, and water supplies have been restored and things are OK. However, in the east and south of the country where the fighting continues, and in the newly liberated areas, things are very tough. This will become even more serious as winter approaches.

What is the most rewarding part of your job and what is the hardest part?

The most rewarding part of my job - there are several. The gratitude that is shown by the local population when they see my teams arrive to start clearance operations & then the absolute joy when the task is finished and the people are able to return to what is left of their homes or farms. The satisfaction that we are training local people to deal with a huge problem of contamination using the best equipment available, employing the safest and most efficient techniques and, in due course, being able to hand control of the task to them.

The hardest part is going out on leave, not knowing what is going to happen while you are away. You plan for the worst but you hope for the best. It is always great to go home for a break (which is necessary) but you feel a degree of guilt that if something happens during your absence you may not be able to help or that you may not be able to get back to Ukraine.

Describe the Ukrainian people and how you see they are coping right now.

The Ukraine people are great to work with. They are very similar to what we (Kiwis) used to be like 30 years ago. They work hard, they play hard. They are physically tough but they are extremely generous and compassionate to those in need. There is none of the PC nonsense that has infected other parts of the world. If there is a job to be done, they will get on and do it.

Does your family back in New Zealand worry about your being in Ukraine?

Yes, my family is worried about me being here. But with modern communication links such as Zoom, WHATSAPP & the like, we stay in frequent contact. My mother, as the good Catholic she is, tells me she includes me in her daily rosary.

Gallery