Reflections: Education and the Marist Fathers

French priests of the Society of Mary were the backbone of Catholicism in New Zealand’s pioneering days. They bore the letters SM after their names but became known generally as Marist Fathers, or just Marists. In the early days they roved the country bringing Mass and the sacraments to the scattered faithful.

The Society of Mary was born and headquartered in France. (Please note, use of the name “Marists” in this article does not refer to the Marist Brothers.) As a religious order the Marists served the mission fields of the Southern Pacific. One priest, Fr Peter Chanel, was canonised as a saint and martyr after being murdered on the island of Futuna. His death led to the community’s conversion to Catholicism en-masse.

Marists in early New Zealand ranged from Bishop Pompallier helping with preparation of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, to tough types braving the broad rivers and treeless plains of Canterbury to visit their flock. The first Bishop of Christchurch was a Marist. English-born Bishop John Joseph Grimes SM. Having studied and taught in France, Ireland and the USA, he was able to mix with the mainly Irish Catholics in Canterbury and Westland. He was fortunate to have mainly fellow Marists to develop parishes throughout the diocese.

For many years the main thrust of the Marist priests was serving in parishes. The Society of Mary established a seminary near Napier and soon New Zealand-born priests were being ordained. Marist priests ran many parishes, including Greymouth, Hokitika, Timaru, Waimate, Temuka and St Mary’s until the 1980s.

Bishop Grimes’ successor, Bishop Brodie, was not a Marist. He became involved in some feuding with the Marists between 1916 and 1921. One issue was the Marists’ hold on parishes in the diocese, principally St Mary’s, Christchurch. This centrally based parish extended over a vast expanse of the city. Bishop Brodie wanted to take St Mary’s from the Marists to become a parish of the diocese. The Marists opposed this and were backed by Church law. The bishop then chose to divide the parish and create new ones. Under Church law, the new parishes remained in diocesan hands.

Another issue was the Marists’ proposal to develop a novitiate in Christchurch for boys interested in becoming Marist priests. Bishop Brodie refused this request, saying it did not fit in his “plans of diocesan organization and development”. Relations between the bishop and the Marists might have been soured but correspondence between them in the following years showed the bishop was generous towards the Marists and they, in turn, came to regard him as a model of piety and empathy.

The Marists saw Catholic education as a vital mission. Many Marist priests were trained as teachers to work in Marist schools, where they could foster boys to consider priestly vocations. In the first 50 years of St Bede’s, 120 Old Boys were ordained priests, 72 of them Marists.

Bishop Grimes, in 1908, proposed the establishment of a secondary boys’ boarding school in Christchurch. He invited the Society of Mary to supply priest-teachers for the school. The Marist Provincial in Wellington, Fr P Regnault SM, supported him. In 1911, the so-called St Bede’s Collegiate School opened at the intersection of Ferry Road and Fitzgerald Avenue, with 20 pupils. Classes ranged from Form 1 (Year 7) to a level preparing students for university studies. The site, the original Nazareth House retirement facility, was too small to accommodate boarders but was intended to be an interim location until a permanent site could be found. The Ferry Road section was too small for sports, so students took the five-minute walk to Lancaster Park for their games. Unable to man a full rugby team, the school adopted “soccer”, along with cricket, as the main codes.

The name of St Bede was applied to the Christchurch school in recognition of its English traditions. St Bede had been a most learned Benedictine Monk at Jarrow in northern England.

A 20-acre block of farmland on Main North Road, Papanui, was purchased in 1914. Almost at the gate was the terminus of the Cashmere-Papanui tramway, so handy for dayboys. In short time more adjoining land was bought. Much of the land would be farmed by the Marists through the next five decades. Cows provided milk for the boarders and pigs generated revenue for the college accounts.

Construction of school buildings was delayed by World War I. Building began at last in 1918 and the newly named St Bede’s College moved there in 1920. On the school roll were 54 boarders and 38 day-boys, including 23 from the Ferry Road site. The boarders came mainly from rural Canterbury and the West Coast.

Some of the farmland was whittled away over the years as extra sports grounds were developed and new buildings erected. Some of the land was sold for suburban housing development. More than a century later the Society of Mary still owns and occupies the college property, though many aspects of it have changed.

The Marists did not always own it. The common understanding had been that the Society of Mary, with responsibility for the property as an educational establishment, would be vested as owner. However, a clerical error in the Land Court offices vested the Bishop of Christchurch, representing the diocese, as legal owner.

When the mistake was discovered, the Marists were irked. The matter simmered for years. Bishop Grimes died in 1915. His successors, Bishop Brodie and Bishop Lyons, would not take legal action against it. On one hand, people argued that the people of the diocese had contributed greatly to appeals for money to finance the school, therefore the diocese should own it. On the other, Marists claimed the public contributions were targeted specifically for the college, so the Society of Mary should be the legal owner.

Documents in the Diocesan Archives show that Bishop Joyce, installed in 1950, settled the issue. After seeking advice from Archbishop McKeefry in Wellington, and counsel from Christchurch solicitor Mr R J Loughnan, Bishop Joyce instigated court action and the error was amended in 1952.

The error was partly attributed to two Marist priests who, after being appointed trustees to the college property, had moved overseas (separately) and were difficult to trace. One, Fr Graham, was the school’s original Rector.

A later Rector, Fr John Dowling, in 1946 proposed an advanced training institution for Marist priests, in Christchurch. He had found a suitable site on Park Avenue (possibly Park Terrace). It was available for sale and he was confident of obtaining the property if he acted quickly. He sought approval from Bishop Lyons to tender for the land. The bishop flatly refused. He said Fr Dowling should have sought advice and opinion as clearly required for any religious house or foundation.

Initially, the college’s main building was a single, three-storey, brick building with concrete facings. It looked odd, sitting alone at the far edge of a boggy paddock. Fortunately, the plans were for two wings to be added when the school roll grew. Both end walls were of timber, able to be removed for the additions. The wings were erected in later years, each attached to the first building and projecting forward. The north wing was completed in 1925 and the south wing was added in the late 1940s. All three together presented a more balanced and impressive sight.

That vista is no more. Thirty years before the 2011-2012 earthquakes, the central block and north wing were condemned as earthquake risks and demolished. Hence the current appearance of a lean-to massif leaning on the south wing.

St Bede’s was progressing solidly as student numbers reached 146 in 1929. But times could be tough. The 1918-19 influenza pandemic and the poliomyelitis outbreak in 1925 forced the closure of schools, severely upsetting learning. The Great Depression of the 1930s reduced people’s incomes to the extent that many could no longer pay school fees, especially for boarding. Numbers of students dropped sharply and college revenue was slashed. Two World Wars brought the deaths of 47 St Bede’s College Old Boys, two in the first war when the college was still very small, and 45 in the second.

Commander of the New Zealand Army Division in World War II, Lieutenant-General Sir Bernard Freyberg VC, later Governor-General of New Zealand, wrote to the St Bede’s Old Boys’ Association to praise the Bedeans who had served in World War II. He expressed “deep appreciation” specifically for the courage and tireless assistance of Marist priest-chaplains.

As student numbers declined in the Depression years, the discovery was made that substantial numbers of Canterbury boys were boarding at St Kevin’s College in Oamaru. This led to allegations by the Marists that the Christian Brothers down-south were “crossing the border” (Waitaki River) and poaching students. Letters held in the Christchurch Diocesan Archives reveal Bishop Brodie’s anger. He wrote to Dunedin’s Bishop Whyte, calling “attention to the unauthorized activities of the Christian Brothers in my Diocese”, and citing statements from Episcopal Legislation, Canon Law, and Papal Commission, to support his complaint. Bishop Whyte denied any wrongdoing.

Bishop Brodie then wrote to all parishes in the Christchurch Diocese claiming an “undue proportion of boys of the Diocese of Christchurch (are) being sent to St Kevin’s”. He urged all priests “to unite with me in a supreme effort to get better patronage for St Bede’s” and begged the clergy to “cooperate generously with me to retrieve the position”.

Roll numbers grew again from 1941. The 1940s and ‘50s became known as “the great expansion”, as student numbers soared from 180 to reach 548 in 1959. This included 232 boarders, so the college was cramped.

More teachers, classrooms, dormitories, and boarding facilities were needed. A document in the Archives shows Department of Education inspectors criticised the inadequate college library and demanded the college meet regulatory standards regarding curriculum and teaching.

In one case, St Bede’s hired a woodwork teacher and provided two elderly huts where he could teach, stating that this should be enough to meet the “requirement to teach Arts and Crafts”.

The college’s glorious 1929 chapel stood separately from the main block. Beyond that was ample space for new buildings. Two long brick blocks of classrooms, a hall/gymnasium, and a two-storeyed science block with sports changing facilities were significant additions through the 1950s and 60s.

As a private school, St Bede’s received little financial aid from the Government then. This meant few lay-teachers were employed. Priest-teachers received little more than “pocket money”. By the 1960s, academic staff numbered about 25 priest-teachers and 5 full-time male-lay teachers. By the 1980s, priest numbers were declining. Integration with the State Schools system then provided State salary rates, paid by the Government. It was a “lifesaver” for St Bede’s.

A different St Bede’s emerged in the first decade of the 21st Century. The first layman Rector, Mr Justin Boyle, led an academic staff of more than 50 full-time female and male lay-teachers in a Catholic school of nearly 800 students.

Old Boys, and all, may discuss how the loss of Marist Fathers at St Bede’s affects the school’s spirit and the learning of students. But we can only rate the “old days”. Perhaps the opinion of a first-day pupil at the opening of the 1920 building could help. The late Sir Thaddeus McCarthy, who became a Supreme Court Judge and President of the Court of Appeal, complimented St Bede’s in 1960 as: “one of the leading colleges of this dominion…..well established scholastically and on the playing field”.

Written by St Bede's Old Boy MiChael Crean (1960-1965).

This article was first published by the the Catholic Diocese of Christchurch Archives on their website 20 June 2023, and has been republished here with their permission.

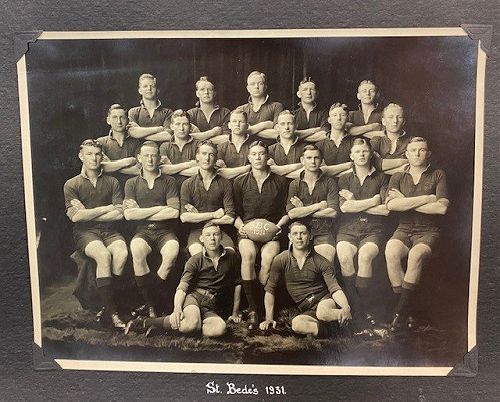

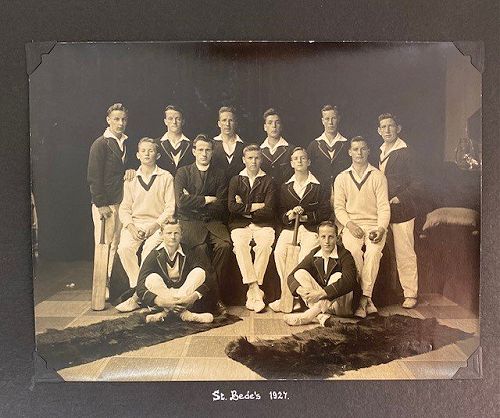

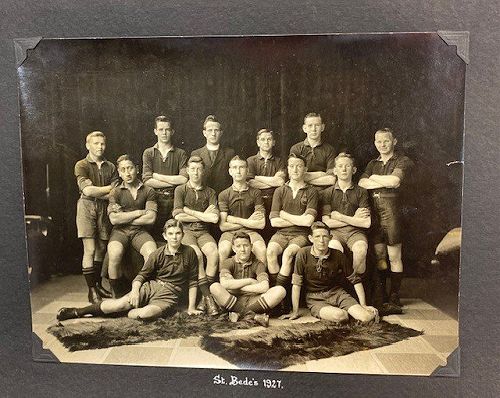

Gallery