ARTICLE: Choose Well as Life is Sacred

Zain Ali discusses how to weigh questions when making a moral decision about life in the Islamic tradition.

Dilemma

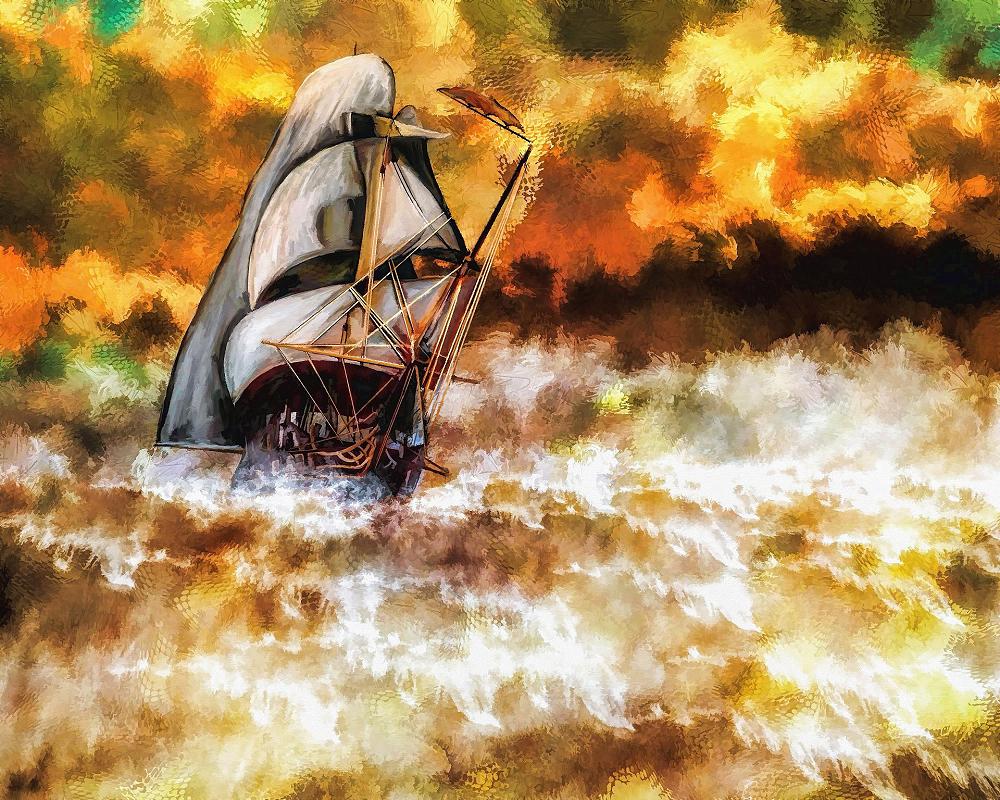

Imagine for a moment you’re on a ship with 300 passengers. The ship has sprung a leak and is slowly sinking. To your dismay you discover it does not have lifeboats or lifejackets. The captain gathers everyone and advises that the ship will be able to limp to shore safely, however, 10 people will need to be off-loaded — thrown overboard to help reduce the ship’s weight. Everything else possible, including all luggage, has already been thrown into the sea. Would you comply with the captain’s advice? Would it be okay to throw 10 passengers overboard to save the other 290? Would this choice ever be morally acceptable?

When I’ve given my students this thought experiment, the majority agree that to do so would be wrong. There are troubling questions. How would you choose the 10? Would everyone draw straws?

At this point, I remind my students that the situation is urgent: we are on a sinking ship. Perhaps we can come up with a criterion: those with a criminal record should be first in line, followed by those who are old — after all, they’ve already lived life.

Flouting concerns for political correctness, one student suggested those who are “heavy” should also be first in the queue. Interestingly, a majority of students felt that a way through this conundrum would be to ask for volunteers — 10 volunteers who would choose to give up their lives to save 290 others. Most students, though, said they would not want to volunteer.

Someone proposed that everyone who believed in God should either volunteer or be thrown overboard anyway. Why pick on religious folk? The reasoning was that religious folk believe in God and an afterlife, so they shouldn’t have any problem sacrificing themselves; they have another life to look forward to. Those who were not religious believe this is the only life they have, so we should let them live it. A win-win solution for everyone!

Making Moral Decisions

The sinking ship thought experiment is said to have been formulated by Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali, an 11th-century Muslim intellectual in Baghdad — which at the time was a cultural and intellectual hub within the Muslim world. He probably used the thought experiment to help his students and fellow intellectuals come to grips with moral thinking within the tradition of Islam.

Al-Ghazali appeals to the right to life in order to provide an answer to the sinking ship dilemma. He contends that it would be wrong to throw 10 people overboard. Throwing people overboard could lead to even more killings (especially if the ship encounters more trouble at sea), and while the survivors would benefit, that solution relies on using other people purely as a means to an end. And most importantly, the benefit to the survivors does not outweigh the need to respect every person’s right to life.

Principle of Right to Life

The right to life, or the preservation of life, is a fundamental principle within Muslim tradition. Its roots are found in Chapter 17 verse 33 of the Qur’an: “Do not take life, which God made sacred, other than in the course of justice.”

This verse is thought provoking and raises challenging questions. What do we mean by life — does this verse refer to human life only? Could it apply to animal life, and perhaps, all forms of life? Do we have to believe in God in order to view life as being sacred?

A student inclined towards atheism said it was possible to view life as being sacred even if you didn’t believe in God — because if we have only one life then it is utterly invaluable.

Even if we do believe in God, what do we mean when we say life is “sacred”? Perhaps it is sacred in the sense that life is a gift, an extraordinary gift, from God.

The last phrase of the verse is intriguing — it seems to suggest that there can be exceptions, that there can be good reasons, or a just cause to take life. What would be a just cause to take a life?

A case in point is abortion: a number of Muslim scholars allow for abortion in cases where a pregnancy jeopardises a mother’s life.

Another case is murder, when the person guilty of murder is liable for the death penalty although this decision rests in the hands of the victim’s family, who have the option to forgive. There is also the case of self-defence, where an aggressor, who is intent on murder, is killed.

Would being in agonising pain and having a terminal illness be a good reason to allow someone to end their life? For many Muslim thinkers the mere fact that life is sacred provides very little room for there being any cause to wilfully end life. And suffering itself can have meaning and purpose. There is also the view that death is something that should be left in God’s hands — we may have free will and autonomy, but we should be patient and wait until God is ready to bring our souls to rest.

I am aware of Muslim medical opinion, which holds that doctors aim to maintain the process of living and not the process of dying — the terminally ill patient should be allowed to die without unnecessary procedures. This view may allow in certain cases for life support machines to be turned off and nature be allowed to take its course.

Life is Sacred

Despite all our scientific advancements, we are faced with hard moral questions. When a person is no longer cognisant of who they are and has no control of their bodily functions, in what sense do they have life?

A Muslim student noted that while he did not support euthanasia, he did not mind it being legal since he recognised that others did not share the same commitments as he did. Some would admire that student’s inclusiveness: others would worry about the spectre of rampant permissiveness.

We should perhaps take a moment to reflect on the advice of Dame Cicely Saunders, nurse, physician, writer and founder of the modern hospice movement:

“You matter because you are you, and you matter to the end of your life. We will do all we can not only to help you die peacefully, but also to live until you die.”

Whatever our views, may we agree that life is sacred, that pain and suffering can be managed to a certain degree, and that the process of dying can be infused with dignity.

Dr Zain Ali is a Professional Teaching Fellow in Theology & Religious Studies of the University of Auckland.

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 248 May 2020