Reading Luke 8:4-8 Ecologically

ELAINE WAINWRIGHT points out all the players in the parable of the sower and invites readers to listen and reflect on the ecological message.

Luke 8:4 When a great crowd gathered and people from town after town came to him, Jesus said in a parable: 5 “A sower went out to sow his seed; and as he sowed, some fell on the path and was trampled on, and the birds of the air ate it up. 6 Some fell on the rock; and as it grew up, it withered for lack of moisture. 7 Some fell among thorns, and the thorns grew with it and choked it. 8 Some fell into good soil, and when it grew, it produced a hundredfold.” As he said this, he called out, “Let anyone with ears to hear listen!” NRSV

What a rich year and how challenging the Year of Mercy has been. It has been marked with two proclamations that will shape our living of mercy into the future. On 18 June, 2015, as we looked toward the Year of Mercy, Pope Francis promulgated Laudato Si’, an encyclical letter on ecology and climate. Then almost as a climax to the movement he had begun, this year on the 1st September, World Day of Prayer for the Care of Creation, the Pope pronounced an eighth corporal and spiritual work of mercy: care for our common home.

Pope Francis has invited us as Earth citizens with all other living beings with whom we share our common home, to recognise that we have an ethic of care for our home, an ethic of right relationships within the fabric of this home.

We do not have to look far to see the effects of our failure to care: violent storms are ravaging many lands, devastating the landscape and endangering all living beings; precious resources, like water, are being wasted through lack of care or unethical usage; temperatures soar; and many species are threatened with extinction because their habitat is destroyed. The human community faces many ethical challenges in caring for our home.

In the series of articles that I have contributed to Tui Motu magazine over the past two years, I have invited us to read our sacred story, our gospels, in a way that can shape a new mindset necessary for and supportive of care for our common home. Luke 8:4-8 provides a text for a new ethical reading that can shape the consciousness necessary to underpin our care for our common home.

World of the Sower

Jesus’ parable begins with a focus on the human character, the sower. But we know the sower exists within the rich hybridity of habitat. There are birds and rocks and thorns, good soil and pathways made by human habitants. The ecological reader is invited into the story world that holds together habitat, human and holy. Another way of saying this is that the reader is drawn into the ecological texture of the text. It is this texture that we will explore as shaping our new consciousness.

The readers’ attention is drawn to the “sower” at the beginning of the parable. But the very designation associates the person inextricably with other material elements, namely “seed”. As readers, we are told nothing more about the sower. However, being attentive to elements encoded in the text from its origins, readers may imagine the sower as slave or tenant farmer on one of the large Herodian or Roman estates which were becoming more numerous in first century Galilee. On the other hand, s/he may have been a self-sufficient small farmer, member of a farming family. The sower would have lived attentive to seasons, with their rhythms of time for planting and for harvesting.

Seed, Sowing and Growing

The seed itself is not identified specifically but is likely to be wheat or barley, the two most common agricultural products of Galilee in the first century. The opening words of the parable draw readers into the interconnectedness of habitat and human, inviting ecological readers to be attentive to both in text and contemporary context.

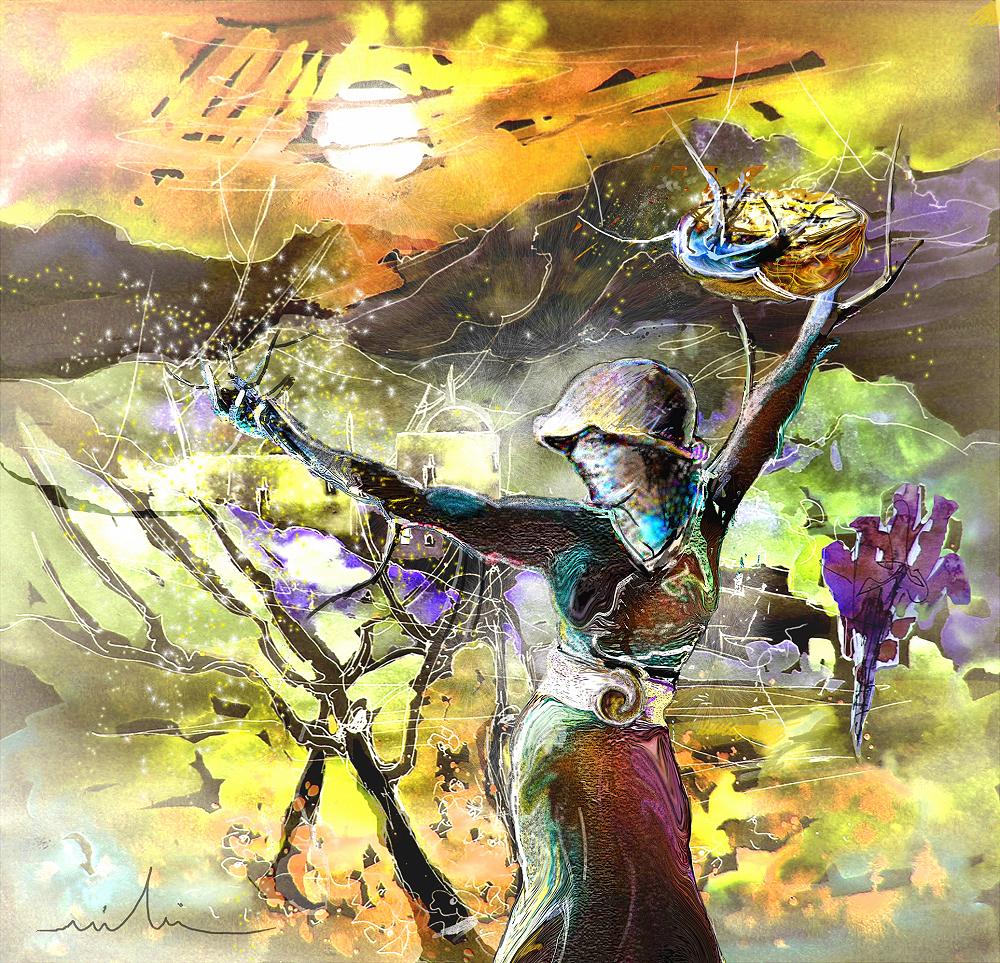

The parable draws the reader into the ecosystem or ecocycle of sower and s Birds take up the seeds eed. Weeds take up their groundspace

The seed seems to have been cast rather than carefully planted in rows but either way it appears to have been hand-sown, linking the sower intimately to the process of planting with the goal of growing grain to feed family and animals and to have seed for the next year’s planting. The pressure on first century Galilean farmers or tenants to produce abundant harvests so as to develop exports for the Empire also lurks within the world that the parable creates, as do similar relationships in many contexts today.

The parable draws the reader into the ecosystem or ecocycle of sower and seed. Birds take up the seeds on the pathway so that they are fed. Weeds take up their groundspace so that there is insufficient room for the sower’s seed in some places. The sun, with the wind and the rain, elements that are not named, enable the seed to grow. However, if the root is not deep enough, some plants will wither under the sun and others will be choked out by plants that are not useful in the agricultural cycle (although they may have uses not explored in the parable). The seed that falls on the soil prepared for it, produces richly.

All this functions metaphorically within the parable which captures a network of actants in this hybrid habitat—from sower, to seed, to bird, sun, earth/soil, weeds and thorns. The reader/hearer is invited into this world.

The Political Aspects

Jesus, the parable teller, and his audience would have known the agricultural system of first century Galilee, the importance of the soil and its various types for particular crops. They would have known too the prolific nature of grain, given the right conditions, as well as the desired harvest in the face of the Roman taxation on a small farmer’s grain or soil. The ancient agricultural writer Varro notes the variety in yields: tenfold in one district, fifteen in another, even a hundred-to-one near Gadara in Syria (Varro, On Agriculture 1.44.2).

Listeners would also have been familiar with an alternative cosmology captured on a coin of Agrippa I who governed Judea in the first century (three ears laden with abundant grains springing from one stalk). It proclaimed the emperor, rather than the soil, as the source of abundance. The ecological texture of the text interweaves the material, the socio-cultural, the economic and other features.

Jesus simply presents these complexly woven worlds in which multiple actants, including the human, are intertwined. Two different cosmologies are implicitly in tension within the parable and the network of associations it creates. First there is that of the emperor and his representatives, whether a Herodian king in Galilee or landowners supporting the imperial system, who are identified as the source of abundance. On the other hand, the parable evokes a more complex system of interwoven elements that intersect in the process of sowing seed. The surprise is that there is an ecology that can produce abundance. Jesus simply invites reflection on, or attentiveness to, the richness of habitat and what such attentiveness will allow us to hear: “Let anyone with ears to hear listen!”

Published in Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 210 Nov 2016: 26-27.