Spiritual Practice in the Season of Creation

Mary Betz discusses how we can further develop an ecological spirituality during this season.

Although first celebrated in Orthodox and Protestant churches, the 1 Sept — 4 Oct Season of Creation was made official for Catholics by Pope Francis in 2015, the same year in which he issued his encyclical, Laudato Si’. In 2021 — the Vatican launched the Laudato Si' Action Platform, a seven-year opportunity to reorient or renew our commitment to simpler, more sustainable lifestyles for the good of Earth and all its inhabitants.

Among the seven Laudato Si’ goals is developing an “ecological spirituality” to enable us to “discover God in all things”. One of the actions suggested toward achieving this goal is choosing a spiritual practice for the Season of Creation, for example, outdoor prayer, journaling our encounters in nature, fasting from practices and possessions that harm creation, or reading the experiences or prayers of those who have found food and rest for their souls in the natural world.

Learning from Thomas Merton

In his hermitage on the grounds of Kentucky’s Abbey of Gethsemani, Tom Merton immersed himself in the wind, stars, clouds, fields, trees and birds who were his daily companions: he called the elements of nature the “spiritual directors” who “form our true contemplation”. He speaks of looking into the sky and “taking it into my head to worship one of the clouds”. Coming to know creation was “the reality I need, the vestige of God in God’s creatures. And the Light of God in my own soul.”

He offers us a long-standing contemplative practice: “When your mind is silent [my emphasis], then the forest suddenly becomes magnificently real and blazes transparently with the Reality of God”.

Merton writes in When the Trees Say Nothing: "I cannot have enough of the hours of silence when nothing happens. When the clouds go by. When the trees say nothing. When the birds sing . . . Here I am, now . . . happy as a coot . . . All I say is that it is the life that has chosen itself for me."

He relishes the hours of silence when nothing happens, when the trees say nothing — and understands that this life chose itself for him. In wordless silence, God meets him in those trees, the earth, the wind, the rain — infusing him with peace and happiness.

The Gift of Contemplation

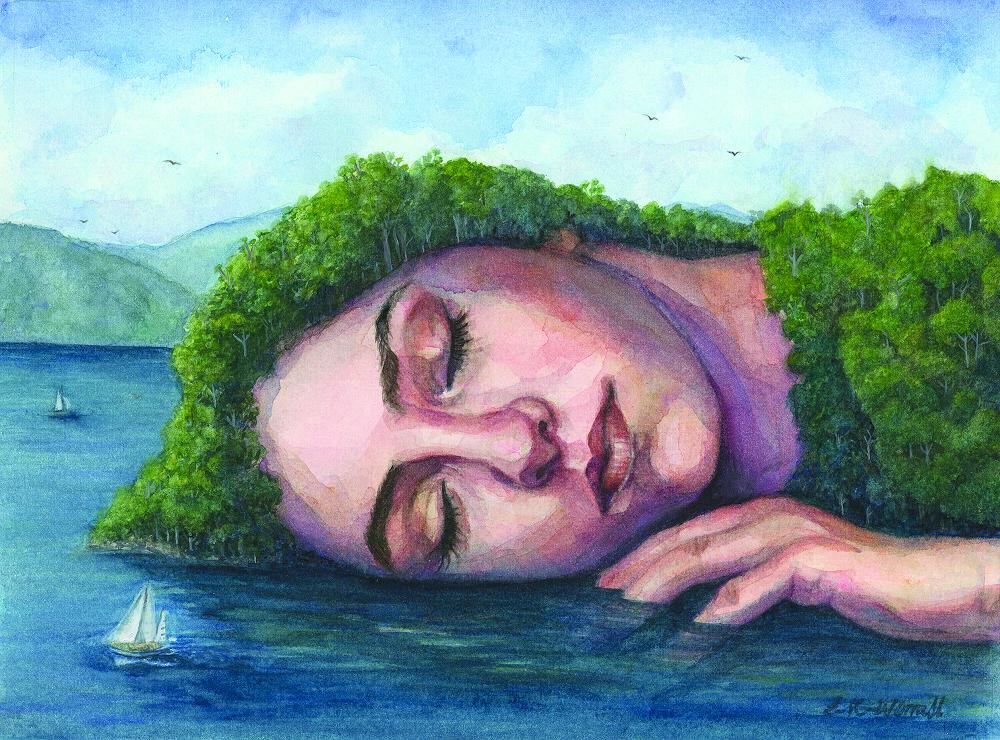

In a 2021 audience, Pope Francis said: “We can contemplate by gazing at the sun that rises in the morning, or at the trees that deck themselves out in spring green; we can contemplate by listening to music or to the sounds of the birds, reading a book, gazing at a work of art or at that masterpiece that is the human face.”

From childhood, I could not find life in prayers most Catholics took for granted. After many years I noticed that I had always been drawn to solitude in nature — following animal tracks in new-fallen snow, photographing cacti in barren deserts, paddling my kayak with a curious harbour seal in tow or coming upon a meadow profuse with wildflowers. Such experiences filled me with curiosity, wonder and awe. Without knowing it, I had been gifted with a form of prayer which fitted me perfectly, one which grounded me and left me with a sense of the peace and well-being in which I sensed God’s shalom.

Similarly, we can gaze at a Monet, dance to Vivaldi, watch the angelic face of a sleeping child, or breathe in the indescribably delicious scent of daphne. Over time, contemplation metamorphises from a way of prayer into the way we live — a way of being.

Ways of Contemplating Nature

Sometimes after time in creation, I journal: “The fog is just lifting from the bay. The tide rises so imperceptibly that the water is glass-like — until small splashes disturb the surface. Kōtare are diving off old, scantily-clad pōhutukawa branches into their liquid larder. A few metres away, overwintering tōrea rest one-footed on sand bars or vigorously probe the sand for crustaceans. Two matuku moana wade slowly in pools of incoming water, keen eyes alert for small fish riding in on the tide. I am so thankful to be in their presence.”

Other times, I walk with my camera, which helps me slow down and be more attentive. I learn the discipline of waiting — for the right light or a break between wind gusts, or for interactions between creatures. Occasionally, binoculars help me study intricate feather patterns on matuku moana or tūī. More often,

I simply walk and allow creatures to catch my attention so that I can listen or gaze at them for a time — a white/green/brown lichen mosaic on a kahikatea trunk, a whiff of jasmine, the rippling notes of a horirerire, the dazzling yellow of the first kōwhai blossoms, or waves lapping and splashing on rocks. There are no limits to how God speaks if we are willing to “waste” time just being attentive.

World Will Be Saved by Beauty

Dorothy Day, the co-founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, periodically escaped the demands of her hospitality house for the poor to retreat to Staten Island or a Catholic Worker farm. She also loved classical music. She immersed herself in the beauty of music and nature, and often said “the world will be saved by beauty”, quoting Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot. Like Dostoyevsky, Dorothy knew suffering and grief. But she also perceived beauty, goodness and truth in her faith, her life, other people and in nature: these inspired and fed her activism for social justice with poor urban workers, farmworkers and the destitute.

In Laudato Si’, Pope Francis writes of “a kind of salvation which occurs in beauty and in those who behold it." He connects attentiveness to beauty with our attitudes toward people and all creation: “If someone has not learned to stop and admire something beautiful, we should not be surprised if he or she treats everything as an object to be used and abused without scruple.”

Fasting from What Harms Creation

Contemplation of the beauty of the universe can save and heal not only the emptiness in our souls — but it can also transform our whole selves. When we appreciate the beauty of the sea, the forests, or one another, we are more likely to act in ways that respect and protect them.

Another spiritual practice that encourages such action is fasting from products or behaviours which are harmful to any part of creation. We might opt to purchase chocolate, coffee or bananas that are “fair-trade” to ensure that any necessary savings are invested in environmentally sustainable and socially responsible companies, to limit our petrol use and consumer purchases and to curb our tongues unless we can speak kindly of another.

We can adopt the Season of Creation as our forebears in the faith adopted Advent and Lent — as seasons in which we focus on transformation to better heal our wounded world. We could not do better than to embrace the silence and beauty of God’s creation. As Martin Helldorfer muses in Prayer, A Relationship without Words: “To stand wordlessly, quietly and at times darkly before God, day after day, changes the way we touch the world.”

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 274 September 2022: 6-7