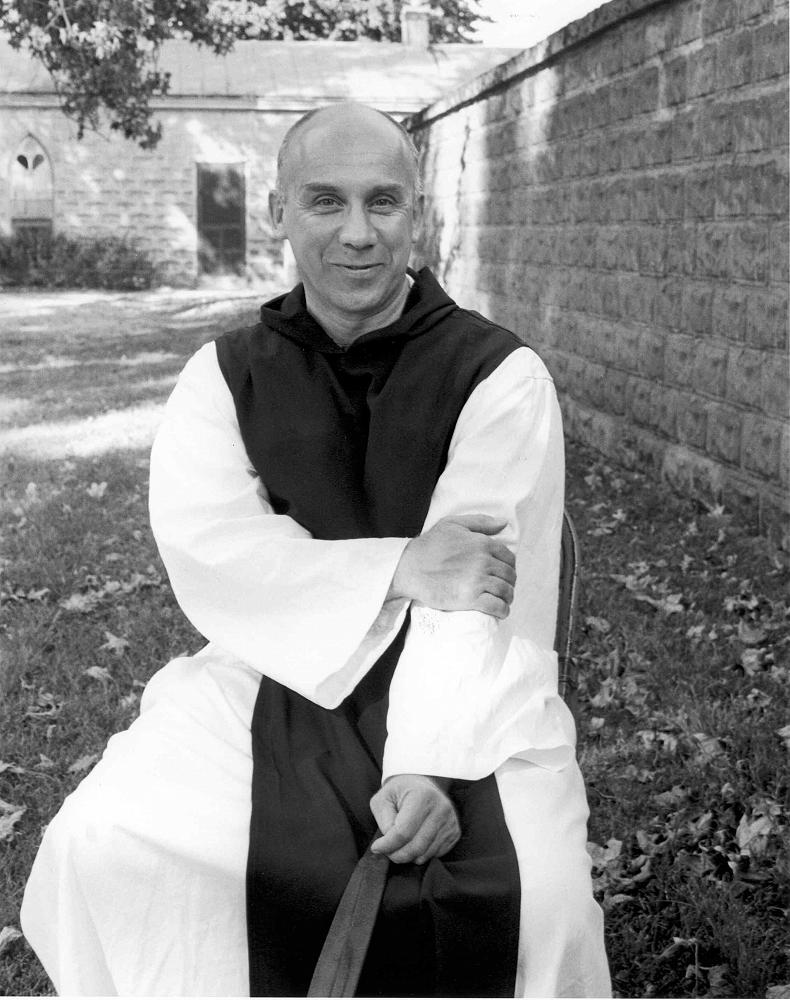

Thomas Merton

On the 50th anniversary of Thomas Merton’s death in Thailand, Jim McAloon traces his influence spreading far beyond the enclosure of his Gethsemani monastery.

When Pope Francis addressed the US Congress in September 2015 he remembered four exemplary Americans who “offer us a way of seeing and interpreting reality”. They were Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr, Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton. Merton (1915-68), a Cistercian monk, was one of the 20th century’s most influential — and prolific — spiritual writers committed to inter-religious dialogue, racial justice and the non-violent path to peace. Tui Motu March 2015 included a number of articles for the centenary of Merton’s birth. This month marks the 50th anniversary of his accidental death in Bangkok, and in this article I would like to look more particularly at Merton’s later years.

Thomas Merton was born in France in 1915 to artist parents. His father Owen was born in Christchurch; his mother Ruth Jenkins, in Ohio. Ruth died in 1921 and Owen in 1931. Having become a Christian and a Catholic in the late 1930s, Merton entered the monastery of Gethsemani, in Kentucky, at the end of 1941 and took the religious name of Louis. Gethsemani was a monastery of the Cistercians of the Strict Observance, commonly known as the Trappists. Merton had shown literary promise at university and his spiritual autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, appeared in 1948. A vast output of essays, books, reviews and poetry followed in the next 20 years (and afterwards). Merton the writer was also a formidable reader, competent in several languages including Latin, French and Spanish.

Roles in Gethsemani

From 1951 until 1965 Merton was successively responsible for training scholastics — monks preparing for ordination — and then novices preparing for final vows. Paradoxically, while fulfilling these responsibilities and reading and writing almost compulsively, Merton idealised other, more solitary or isolated, monastic lives. His journals and letters record his conflicts with James Fox, abbot from 1948-68, who was not always receptive to Merton’s enthusiasms. (Merton could be quite oblivious to the realities of managing, and sustaining, a large monastery!).

Some accounts take Merton’s complaints about Fox at face value, but Merton would not have become who he was without the structured life over which Fox presided. Without Fox’s sometimes cautious acquiescence Merton could hardly have written, and published, what he did on prayer and monasticism, war and peace, ecumenism, engagement with Islam and Buddhism, literature and culture – to say nothing of his voluminous correspondence.

Changing Focus

By the early 1960s Merton was becoming an important figure in the renewal of the Catholic Church. An excellent introduction to the range of his interests and concerns in that decade is Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander (1966), a compilation of meditations, notes on theology, religion, war, racial justice, current events and the quirks of life in the monastery. In contrast with the sometimes world-rejecting language of his earlier work, Merton now made it clear that some monks, at least, had a responsibility to engage with (as Vatican II put it) “the joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties” of the time.

Advocate of Peacemaking

Merton’s concern with war and peace is well-remembered. He registered as a conscientious objector before entering the monastery (his mother came from a Quaker family). From the late 1950s, with the nuclear arms race and then the Vietnam War intensifying, Merton argued that peacemaking was integral to the Christian vocation. The French superiors of his Order attempted to prevent him from writing on these theme, but Merton anticipated and was vindicated by John XXIII’s 1963 encyclical Pacem in Terris.

During these years, Merton made important connections with religious peacemakers outside the monastery. Even in the 1930s he had been influenced by Catherine de Hueck Doherty, whose Friendship House in Harlem had similarities to the Catholic Worker Movement. During the 1960s Merton and Dorothy Day, the Worker’s founder, were frequent (if not always uncritical) correspondents. He also enjoyed warm relationships with Daniel Berrigan, and the theologian and rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. His letters to a younger peace activist, Jim Forrest, are a sustained exposition of a spirituality of peacemaking. In particular, Merton emphasised the importance of persistent witness rather than the illusion of immediate results.

Engaging with Asian Religions

With his responsibilities for monastic formation, Merton thought deeply and at length about monastic theology, and varieties of monastic and contemplative experience. This led him into profound engagement with Asian religions. He wrote extensively on Buddhism, especially Zen, and also on Daoism, Hinduism and Sufi mysticism within Islam. In his own thinking, Merton emphasised the “true self”, the person we are before God, without the illusions and distractions with which we encumber ourselves. Without underestimating the differences, Merton here drew connections between Christian and other mystical traditions. Merton was deeply immersed in the sources of Christian monasticism, back to the Desert Fathers and Mothers of the third century, and his last – posthumous – book, The Climate of Monastic Prayer, demonstrates this, and that he was, always, a monk in the Roman Catholic tradition (and no enthusiast for change for its own sake).

The restless Merton had often dreamed of more solitude and from the 1950s was allowed to spend time alone in a number of places within the monastery grounds. Finally in May 1965, resigning as novice master, Merton was permitted to live full time in a hermitage some distance from the abbey. While devoting more time to prayer and meditation, Merton did not reduce his writing or reading, or, indeed, his correspondence and meetings with men and women who shared his concerns. His hermit life was also disrupted by hospitalisations for various problems. From one such medical episode in 1966, arose a major crisis in Merton’s life – a brief and intense relationship with a young nurse. On this episode we have only Merton’s account; after some months the pair broke off the relationship and Merton renewed his commitment to his monastic vocation.

Leaving the Enclosure

Merton had received frequent invitations over the years to attend conferences or visit other monasteries; his superiors had always obliged him to decline. However, in 1968 a new abbot, Flavian Burns, allowed Merton to visit other monasteries in America and, most importantly, to attend a conference of Asian Benedictine and Cistercian superiors in Bangkok. Merton was permitted to spend several months travelling in Asia (and hoped to visit his New Zealand relations in 1969). In Bangkok, after speaking on “Marxism and Monastic Perspectives”, Merton was accidentally electrocuted by a badly-wired fan. The date of his death — 10 December — was the 27th anniversary of his entry into the monastery.

Merton was profoundly moved in his travels. He and the Dalai Lama met twice and achieved a mutual rapport. At the ancient Sri Lankan city of Polonnaruwa, among the huge statues of the Buddha, Merton experienced a spiritual illumination: “I know and I have seen what I was obscurely looking for.” At a meeting of world religions in Calcutta, Merton emphasised the importance of true communication grounded in fidelity to one’s own tradition and vocation: “We discover an older unity. My dear brothers and sisters, we are already one. But we imagine that we are not. So … we have to recover … our original unity. What we have to be is what we are.”

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 233 December 2018: 26-27