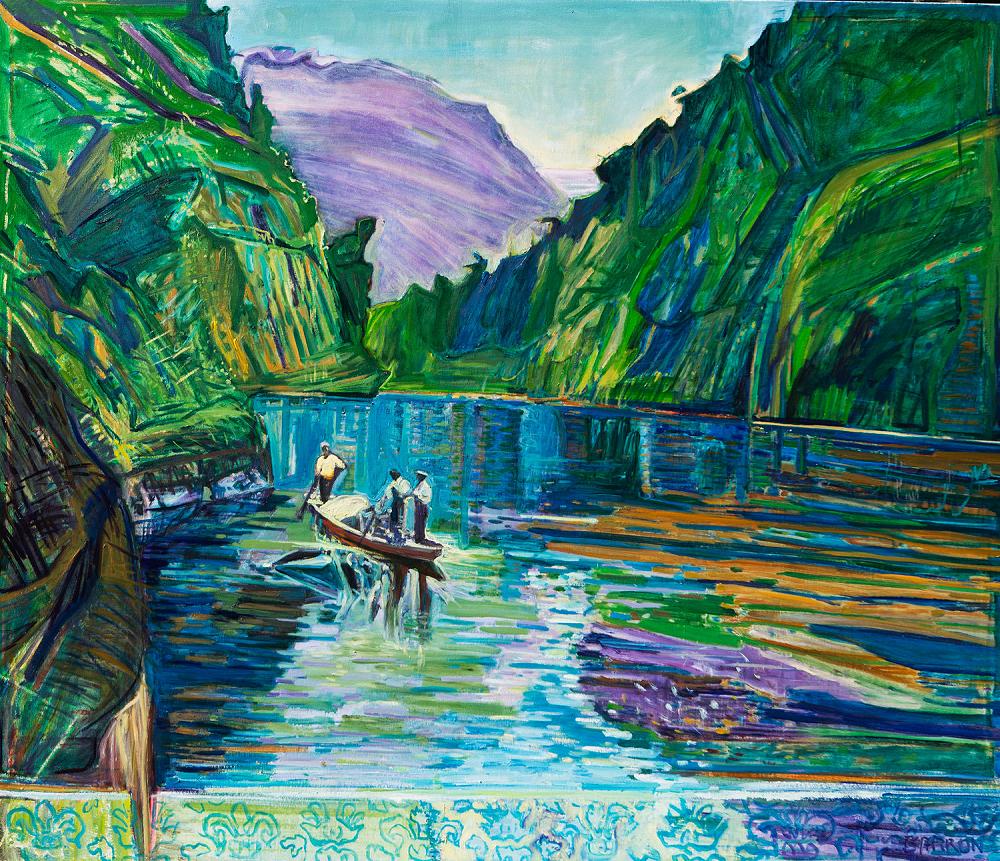

People and River Are One

Makareta Tawaroa shares her experience of living alongside the Whanganui River.

Our Whanganui River is sick, particularly the lower reaches. It is contaminated with faecal bacteria, nitrogen, phosphorus and fine sediment from extensive farming. This is because the river has been used as a dump for years by forestry, meatworks, factories, farms, sewerage and hydro-electricity plants. It will take a long time to clean up.

River Users

The Whanganui River and its tributaries is a highly complex organism. It covers two national parks including the Whanganui River National Park, a national forest, farmlands, several large towns and smaller communities on its almost 300 km journey to Whanganui city, where, up until recently, stormwater, wastewater and sewage flowed into the river.

Because the users of the river — local and central government, commercial interests, recreational users, environmental groups and Iwi — don’t talk to one another, they don’t address the complex river system as a whole. Several groups employ their own experts to produce scientific data on water quality, water temperature and fish life. Other groups ensure they operate within the law and keep abreast of what’s going on around them but none have the whole river system at heart.

Failure of Resource Management Act

Our river is not the only contaminated waterway. All over the country there are waters in a similar state due to the implementation of the Resource Management Act. Many ancestral bodies of water have been seriously degraded because of this Act. The Waitangi Tribunal highlighted the government’s failure to recognise Māori rights and interests in water and recommended sweeping changes.

As a kid in the early 1960s, I remember talk about damming the river for hydroelectricity at Atene, but because the land was too pumiceous the idea was abandoned. That didn’t stop the natural flows of the Whanganui River and five of its upper tributaries from being redirected through huge pipes and canals into the Tongariro Power project. It left only 25 per cent of water to flow back into the Whanganui River, changing the river beyond recognition and breaching the Treaty of Waitangi. The Tongariro Power Project generates only 5 per cent of electricity — it has created so much damage for so little gain.

As an adult I sat in the Wellington High Court listening to lawyers for Genesis Energy talking about the benefits of granting consent to take water from the Whanganui River for 35 years. The concerns of Whanganui iwi were completely ignored.

River Given Legal Personhood Based on Māori Values

Years ago a church women’s group I belonged to identified that the quality of the water was the priority. Five years ago we packed the parliamentary gallery for the third reading of the Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017. Three days later a legal framework, based on Māori spiritual beliefs, was passed into law. The Act granted the Whanganui River legal personhood, with all the rights and privileges of a person.

I offered a silent prayer for all those who had fought long and hard for the mana (authority) and mauri (life force) of the river. I remembered with deep gratitude, Ngā Pou o te Awa, three giants in our river struggle, Titi Tihu, Hikaia Amohia and Sir Archie Taiaroa, all of Hine Ngākau of the upper reaches.

This legislation had immediate repercussions all over the world, thrusting Whanganui Iwi into the limelight, giving hope to many groups whose journey was similar to ours. Many were inspired by our Iwi’s persistence and have come to hear our story first hand. It’s too early to get excited because there are many unanswered questions such as: Will the new personhood status of the river make any difference to the way the river will be used in future? Will this legislation help to clean up the river and keep it clean?

Ongoing Damage

Challenges to the Act from forestry and dam developments are ongoing. The Act did not reverse the existing resource consents — Genesis Energy has resource consent to take water for another 20 years.

Fish & Game New Zealand also has an interest in the Whanganui River. Anglers like to fish in clean water so there are certain arrangements with partners to ensure that clean water is available in certain lakes at certain times.

Promoting the Act

Since Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017, Te Tangata Tiaki o Whanganui — the administrative Trust which was established to receive all assets and responsibilities — has been educating the river people about the responsibilities arising from the Act. I’ve attended several presentations and have been impressed by the young, motivated and skilled Māori who have embraced their duties with cautious optimism.

The Trust is undertaking a five-yearly review of their mandate, looking at the terms and operations of their Trust Deed to see how helpful it has been for our people. Sam Bishara has been appointed an independent facilitator to lead the review. As only 40 per cent of our people live in our whenua, trustees will travel throughout the country consulting with Whanganui whānau, hapu and iwi who live outside our tribal region.

He Awa Ora is a new exhibition on display at the Whanganui Regional Museum which tells Whanganui stories through the voices of our river and taonga. It has photos and rare taonga from the Museum’s Māori collection. It wasn’t all that long ago when kaumātua Manu Metekingi threatened to clear the Māori court because the museum trustees of the time did not want iwi sitting around the table.

The Te Kopuka group is working on a collaborative plan called “Te Ripo” to promote the health and well-being of the river. Te Ripo, kare or ripples, refers to the river’s physical and spiritual vitality and also to the changes heralded by the new legal status of the River as Te Awa Tupua.

Mutual Connection

Understanding the river in spiritual and philosophical terms is a natural part of our lives. Our tribal whakataukī/proverb expresses this idea so simply. Aunty Julie used to say: “The river is my mother and father, my sister and brother … don’t talk about the river, talk to the river.” In law, the river is now recognised as an indivisible and living whole from the mountains to the sea, incorporating all its physical and metaphysical elements.

I remember as a child listening to Koro Titi talk about the river: “If the river is well, the people are well. If the river is sick the people are sick. The people and the river are one.” Our identity comes from the river. My cousin Anatipa Morvin Simon would often remind us that the river was our first road, our first larder, our first playground, our first bathroom, our school and our holy water font.

As iwi we want to leave the river in a better state than it is now so that we can say: “Ka ora te awa. Ko ora te iwi. The river is healthy. The people are well.”

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 272 July 2022: 5-5