Part Three: An Ecological Reading of Mark's Gospel

In this third article in the series Elaine Wainwright explores Mark 3:20-27 and the New Testament worldview as a way of un-derstanding demon possession.

The second article of an ecological reading of Mark closed with Jesus casting out demons (Mk 1:39) — “many demons” in an earlier verse (1:34). We gave this demon theme brief attention yet it is one of the key characteristics of Jesus’ ministry in Mark’s gospel. Jesus named his ministry as the basileia/kin[g]dom/empire of God being near at hand (Mark 1:15). I suggested that we might express that metaphor today as God’s dream or God’s transformative dream for the universe and for the Earth community within that universe. In light of this, how then might we re-read demon possession and the casting out of demons? The text which I’ve chosen as a focus is Mark 3:20-27.

Jesus’ proclamation of the basileia of God has been characterised by healing or the restoration of right relationships with/in human bodies (1:29-31, 32-34, 40-45; 2:1-12; 3:1-5, 10). It is also characterised by the confronting of unclean spirits or demons which were said to possess human persons (1:21-28, 32-34, 39; 3:11-12, 15). The interpretation of aspects of first century sociality as demon possession was characteristic of a cosmology that we do not share today. However, we need to understand this cosmology so that we can do an ecological reading of the Markan theme of demon possession.

From classical worldview

Much of the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament reveals a classical cosmology, namely a three-tiered universe: the heavens above, earth in the middle, and the underworld or Sheol below. God, or the gods, inhabited the heavenly realm, the human community the earth and those humans who had died, the underworld.

To Hellenistic worldview

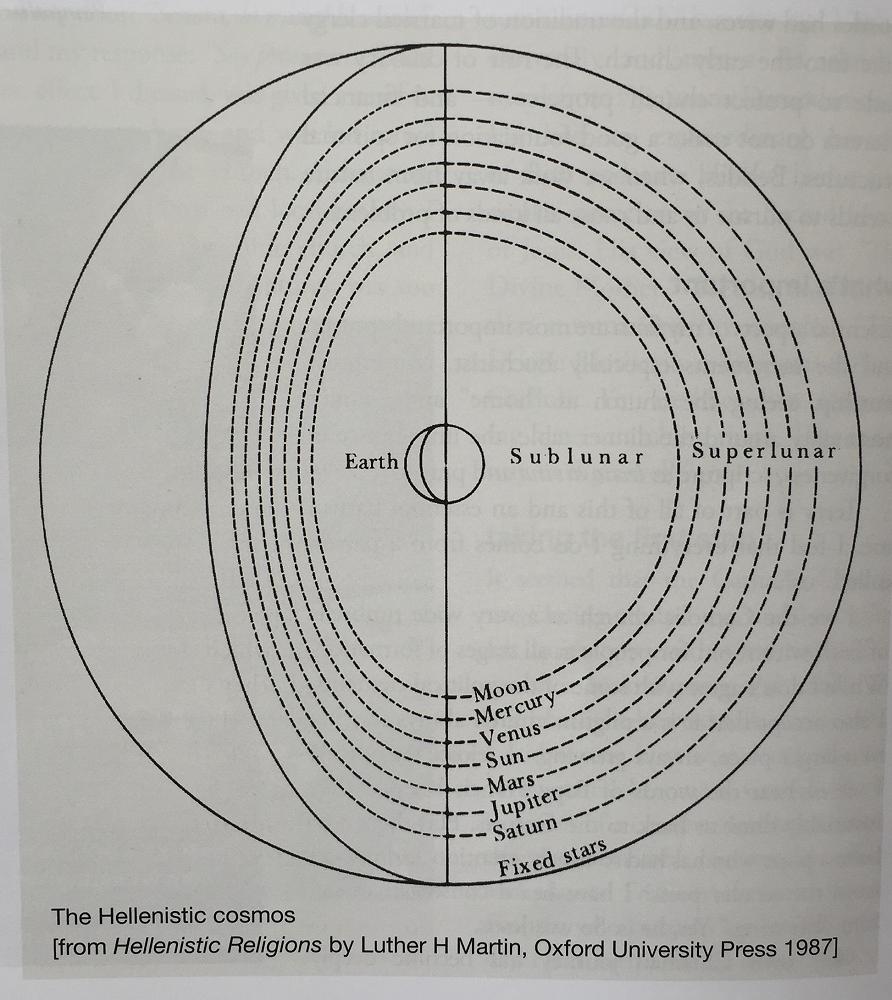

In the Hellenistic period there was a significant shift in cosmology as a result of the insights of philosophers, astronomers and other ancient thinkers. They taught that while the earth was at the centre of the cosmology, and it was surrounded by seven planetary spheres or orbits. The moon, as the closest to earth, marked out the sublunar realm while the other planets and stars made up the superlunar realm. The cosmic space that constituted the sublunar realm was populated not only by humans as earth-dwellers but also by powers and spirits, including the demonic. It is this shift in worldview which led to the significant presence of the demonic in the gospel narratives.

To Copernican worldview

As contemporary readers, we know of two further cosmological revolutions since the Hellenistic. The first was the Copernican or heliocentric, namely that the earth and other planets revolve around the sun in an elliptical orbit.

To evolutionary cosmology

The second is that which is currently unfolding: a universe that can be traced back to the Big Bang around 14 billion years ago. Planet Earth is estimated to be approximately 4.5 billion years old, with the first signs of life emerging on this planet between 2 and 3 billion years ago and human life only in the last two million years. All these processes are part of a creative unfolding.

It is with this scientific knowledge and worldview, or cosmology, that contemporary readers approach the gospel narrative with its world of demons and demon possession. As ecological readers we know we are not reading with a Hellenistic lens. We use the lens of contemporary ecological justice, informed by the gospel’s socio-historical context that has left its traces in the text.

Order is disturbed

Returning to the Markan gospel, we find Jesus in Mark 3:20 in his house after having called twelve followers to share his ministry. Crowds have formed spontaneously seeking his healing and liberating ministry. They disrupt any attempt to withdraw, even time to eat. The Greek draws into the narrative the material substance, bread, in the concluding phrase “not able to eat bread” (3:20). The ecological reader notices the materiality of the bodies of those gathering as “crowd” around the physical structure of the house. Traces of all these elements remain in the text. As the narrative unfolds, the reader encounters two responses to this summary description of Jesus’ ministry.

The first is the response of Jesus’ family (3:21). They hear things about Jesus. Their senses are alert as information is conveyed. They respond by going out into the public forum where the crowds are gathered, in order to take hold of Jesus. This is a physical response — one body meets another, either forcibly or not; the verb leaves the ambiguity in place. They verbalise their reason. The bystanders in the narrative hear it and so do the readers of the story — he is out of his normal state of mind or one could say, out of his normal way of being human body in a socio-political context. In a world in which kinship was the foundation of society, the family’s criticism of Jesus points to his profound revisioning of the fundamental socio-cultural structure and belief system. This is augmented in the story by the later verse about Jesus’ family in 3:31-35, a short text that you might want to read here.

The second response to or interpretation of the crowd’s acclamation of Jesus’ ministry comes from ‘the scribes’ (3:22). They are described in relation to place, but a place other than that in which Jesus’ ministry has unfolded. They have come down from Jerusalem. Previously in the story (1:5) people from Jerusalem came to John to be baptised, and they came from Jerusalem to Galilee (3:8) as a result of hearing what Jesus was doing. In 3:22, the scribes come down from Jerusalem to critique Jesus. The worldview in which they express that critique is the Hellenistic world view of demon possession. They accuse Jesus of “having” Beelzebul, the ruler, the one with power over all demons. Jesus is said to be possessed by the most powerful of demons, those powers who inhabit the sub-lunar realm of the Hellenistic world view. The scribes go further to interpret the work of Jesus that freed people from the power of demons as being informed, empowered by Beelzebul. This language of power demonstrates one of the arenas in which demons and demon possession functioned — in the realm of power. In this instance, the power being constructed and attacked is primarily religious and then political.

As the encounter between Jesus and the Jerusalem scribes continues, Jesus uses two parables that draw in material and socio-political language and imagery (that of a kingdom and of a house) to speak of the demonic. Divided within they will destroy themselves. Clearly Jesus cannot belong to that world if he casts the demons from their places of power in that world. The segment closes with language and imagery of power but here it is the imagery of a householder who would defend his property from the thief unless he was himself tied up. Jesus’ casting out of demons, his power as spirit-infused restorer of right ordering in the universe (1:10-11), is understood in relation to the right order of the cosmic sub-lunar realm through a Hellenistic cosmological lens. The contemporary ecological reader can read it in relation to the restoration of right ordering of/on planet Earth.

During the Lenten and Easter season, this language, imagery and cosmology take on an even more profound hue.

Published in Tui Motu magazine April 2015.