Reading Luke’s Gospel 1:1-4 with Ecological Eyes - Part 1

In the first part of this new series Elaine Wainwright interprets the Lucan prologue Luke 1:1-4 together with the commissioning of Jesus in Luke 4:14-21.

As we read the Gospel of Luke, the gospel of divine compassion, we will attend to the images of mercy that this gospel constructs. We shall ask how mercy speaks to and within the human community and the whole Earth community.

Two significant documents will be our dialogue partners in our reading. The first is Pope Francis’s Misericordiae Vultus (11 April 2015) promulgating the Jubilee of Mercy and the second, the encyclical, Laudato Si’, On Care for our Common Home (24 May 2015). The dialogue between these documents and Luke’s gospel will produce a new fabric of interpretation.

In this first part we will bring together Luke 1:1–4, the unique Lucan Prologue, and the commissioning of Jesus in Lk 4:14–21, also found only in Luke.

The Prologue takes readers immediately into the interconnection between the material and social worlds that characterise both the narrative and also its production and dissemination.

The reader meets the “many” who have undertaken to compile or to write a narrative of the Jesus stories that had been shaped through decades of oral traditioning. Storytellers in the Lucan communities would have been forming narratives from the different traditions about Jesus going back to eye-witnesses. They were shaping these into a new narrative — “an orderly account”.

An Orderly Account

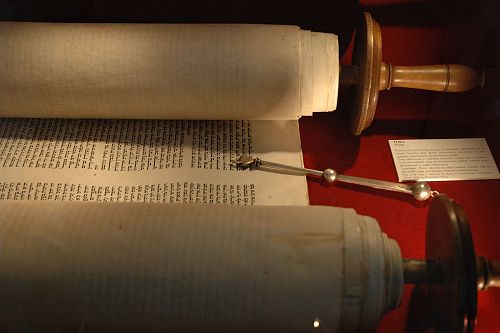

It is this “orderly account” in its written form that links the material and social worlds of its readers. It evokes the papyrus plant that was processed to form the sheets on which the orderly account of the Jesus story was written and which, in their turn, were sewn together to form the biblos or book. They can remind us as contemporary readers of the long history of “orderly accounts” written on different types of materials — beautifully illustrated leather-bound books, early printing press texts and today’s texts read via electronic media — to name a few. Without these, we would have no “orderly account”. The Jesus story reaches us in and through the unique interaction of the material and the social.

This is made specific in relation to the unfolding Lucan narrative. The narrator claims, at the outset, to have investigated the traditions around Jesus that have been circulating over decades. In this process, time, story and narrative skill come together in order to communicate the “truth” contained within this narrative tradition. And it is an element of “the natural environment” named by Laudate Si’ (par 95) as the “collective good” of all humanity that is its carrier.

The “natural environment” and its elements will be the carrier of the Jesus story and will be woven into it. In Luke 4:14, the narrator says that Jesus goes to Galilee following his encounter with the tempter (Lk 4:1–13), “filled with the power of the Spirit”. The work of this “filled” one can take place only in a natural environment. Similarly the built environment of the Galilean synagogues also becomes the context for his teaching and winning the praise of everyone (Lk 4:15). Without these environments and Jesus’ interrelationship with them, there is no orderly account.

Jesus' Hometown

Luke 4:16–17 tells of a more specific material context for Jesus’ unfolding mission. It is the village of Nazareth, where Jesus had been brought up, the text reveals. Jesus is grounded in this physical place—its people, its buildings, its food resources and more.

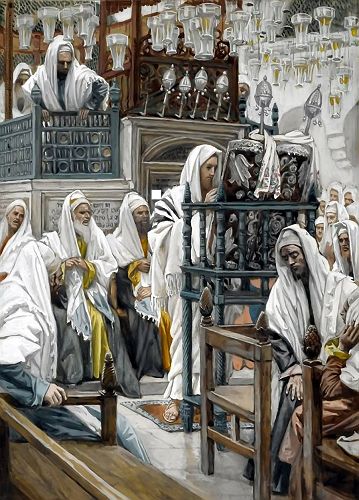

Place and time link Jesus even more to Nazareth. On a particular Sabbath he enters the synagogue “as was his custom” and takes up the task of reading from the scroll of the prophets. Here the text alerts readers to the “interrelationship between living space and human behaviour” (Laudate Si’ par 150), elements of an integral ecology.

The human behaviour that unfolds in the Nazareth synagogue is like a slow motion film. Jesus stands up to read, to participate in his Jewish synagogal ritual. An attendant hands him the scroll of the prophet Isaiah, the roll of papyrus, the material on which the text has been written as is the “orderly account” that is the Lucan gospel. Jesus then unrolls the scroll, respectfully handling this material that carries the prophetic words of the one named Isaiah. The narrator indicates that Jesus’ choice of text is very deliberate: “He found the place”.

According to the Lucan narrator the text Jesus reads is a segment of Isaiah 61:1–3 — with minor alterations and additions. Here the prophet claims the outpouring of the Spirit as an anointing for a prophetic ministry — to bring about a change in the lives of those who are poor, captive, blind and oppressed. To such a mission we could attribute the words of Pope Francis in Misericordiae Vultus:

“. . . the mercy of God is not an abstract idea, but a concrete reality with which God reveals God’s love as of that of a father or a mother, moved to the very depths out of love for their child. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that this is a ‘visceral’ love. It gushes forth from the depths naturally, full of tenderness and compassion, indulgence and mercy” MV par 6.

Jesus Claims Ministry

Jesus claims the Isaian ministry of mercy and justice as his own, first with his body and then by his words. He rolls up the scroll, gives it back to the attendant and sits — as he is participating in the liturgical ritual. He then proclaims that the scripture is fulfilled in their hearing, in the profound interrelationship of human bodies, human spirits and material contexts. However it is only as his mission unfolds that readers will encounter Jesus as he touches the eyes of the blind, releases those captive to evil and brings healing to the poor and afflicted.

Jesus’ ministry of compassion and mercy that unfolds with and in the Lucan “orderly account” is one of active engagement with and in the “natural environment” or “living space” and with “human behaviour”, terms used within Laudato Si’.

Engage in Year of God's Favour

The contemporary ecological reader may then hear the anointing for a

ministry of compassion and mercy as extending beyond the human community to the

more-than-human community. Those who are “poor” could include not only those

among the human community who are bereft of the most needed resources but also

those other-than-human species that are bereft of habitat.

“Captives” may include those cut off from life-sustaining food supplies. The “blind”, those species affected in myriad ways by the toxins that the human community pours into Earth’s systems. Humans and many other-than-humans cry out from under the oppression resulting from so much “human behaviour”.

In the prophetic proclamation of the Jubilee Year of Mercy, Pope Francis calls us, as does Jesus through the words of the prophet Isaiah, to engage in a year of God’s favour. This will happen if like Jesus, we work to bring about justice and compassion for the human and the entire more-than-human community.

Tui Motu InterIslands Magazine. February 2015

Gallery