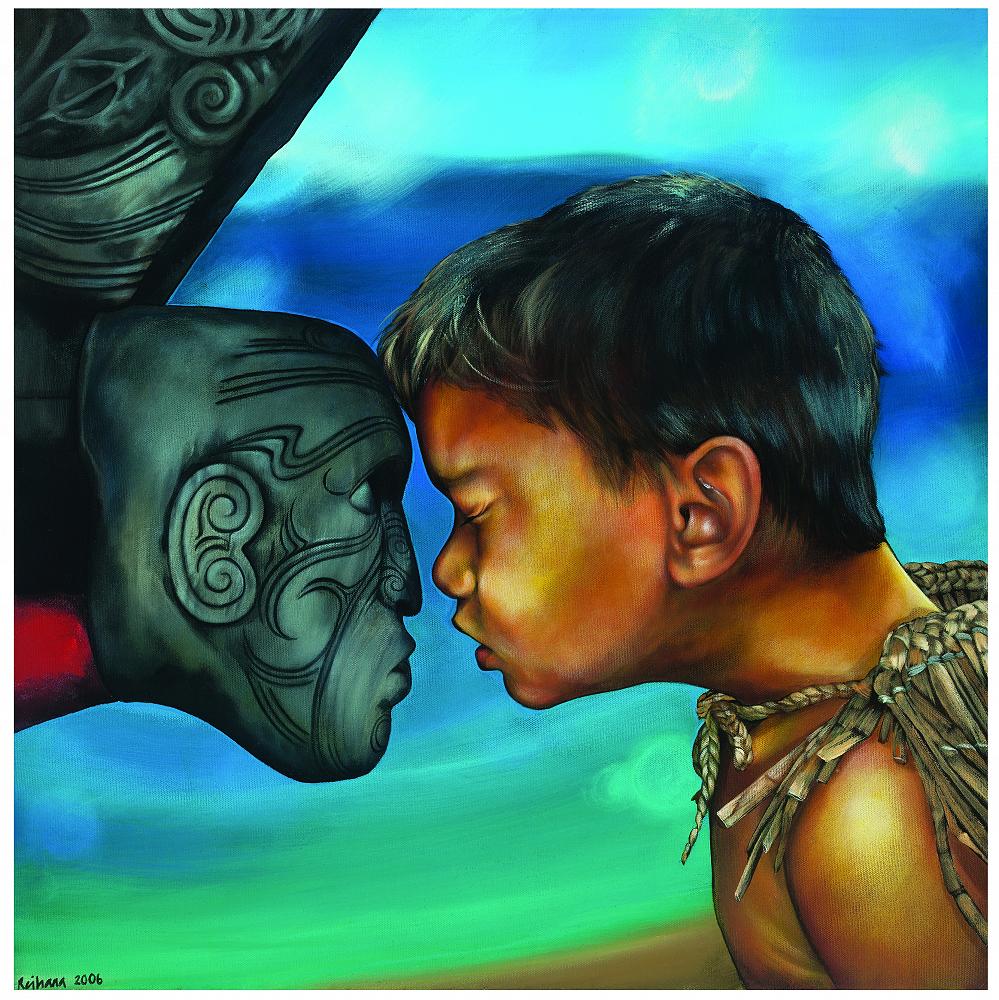

Sacred Life from Common Bones

Makareta Tawaroa writes that Māori knowledge is needed in government decision-making.

As the number of people out of work continues to grow, many Māori households and communities will face huge problems because of structural racism. Most New Zealanders will find this hard to accept but there is one very simple reason why it is true. It is because we still live in a settler, colonial society, where policies are mainly supportive of the dominant culture. In Aotearoa the State is the product of British colonial expansion — its characteristics reflect these cultural and imperial origins. But the problem runs deeper than gloss and appearance — the real problem lies in the ideas that motivate the people who run our State.

Inequalities Magnified

I agree with First Union President Robert Reid, who said recently that the welfare system is a two-tiered system — one for Māori and Pasifika beneficiaries and one for Pākehā beneficiaries. The inequities that currently exist are magnified by the Income Relief Payment. For example, if you lost your job (including self-employment) from 1 March 2020 to 30 October 2020 due to COVID-19, you may be eligible for the COVID-19 Income Relief Payment. This gives up to 12 weeks of payments to help with living costs after a sudden job loss and allows time to find other work. The scheme works well for those who fit into these categories — but many Māori and Pasifika do not.

Involvement in Decisions

All of New Zealand has now moved to Alert Level 1, and our attention is moving to the long-term repercussions of the pandemic. It is critical that Māori and Pasifika be involved in the decision-making recovery process as the recession will hit them the hardest. Māori and Pasifika communities will carry a higher level of risk to health, livelihood and wellbeing in this new environment. Infection and death rates will be highest for Māori and Pasifika of all ages if community transmission escalates.

The social and economic impact of the pandemic will be felt for longer and more intensely for our people who live in precarious conditions. There is immense pressure to fast-track economic recovery — a recovery which will be largely designed by non-Māori, and will deepen the pre-existing inequities.

There is a large body of knowledge around mātauranga Māori which is being completely overlooked. It is time to draw on both systems: Māori knowledge and ways of knowing, and Western science. We need both systems to inform our expertise, experience and leadership.

Reconnecting

Recently my cousin Bob came home to live because he was unable to find affordable accommodation. He got tired of living in a tent on a beach in the Bay of Plenty, particularly in the winter. He had become estranged from his wife many years ago and was sad that he had not been reconciled with her before she passed away. He became very depressed. His favourite daughter lives in Australia so he feels lonely most times. He is estranged from his two other daughters who live in their childhood home which had belonged to their mother. She had come from the Bay of Plenty. Bob came home for a tangi and had, after a few false starts, decided to stay. He now lives in an old family home, cooks on a barbecue and lives off the grid with his dog Rowdy.

In the middle of Lockdown Bob joined a small group of kaumātua and kuia who meet weekly on our marae. The programme is flexible and we have a lot of fun. Most of us are his cousins though he doesn’t know us very well. We all share a common ancestor and whakapapa which makes us whānau in the true sense of the word. We come together because we want to be something greater than we would be on our own.

Cousin Bob’s main problem was housing. Housing costs are the single largest contributor to the poverty gap. Even those receiving the Accommodation Supplement say that nearly three-quarters of their income is spent on housing and that rents are raised in equal proportion to the increase in the Accommodation Supplement.

Understanding Māori

I listened to a radio programme recently that was trying to define who is Māori and who is not, including the pros and cons of the Māori electoral roll. There were all sorts of definitions being touted. It was not a well-informed conversation.

One of the injustices that has been done to Māori is to take away our right to define who we are as Māori. Pākehā have defined the terms. If you look up the word “tribe” in the dictionary, it says “a primitive social group”. A “sub-tribe” is “a subset of a primitive social grouping”. This is a very inadequate explanation.

I like to look at what our people say the words mean. For example, the word iwi is part of the word koiwi which is our bones. When a woman is pregnant with a child she is hapū. When she gives birth to a child the act of giving birth is whānau. Therefore a Māori child is whānau from a hapū woman descended from common bones.

This describes the network of relationships which define who we are as Māori. The important thing about this network is that we cannot separate whānau, the act of giving birth from hapū, the state of being pregnant. We cannot separate hapū from the common bones of shared ancestors. We cannot isolate out an individual whānau from the hapū which gave birth to it and the iwi of which it is a part. This whole of integral relationships is more than “a primitive social group”.

I have been following the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care. Our vulnerable tamariki and mokopuna could have been saved from horrific abuses if there was a better understanding of the importance of Māori relationships. My cousin Terry spent 25 years in Porirua Hospital simply because his occasional epilectic fits were poorly understood by medical practitioners and he was diagnosed inappropriately.

Working with Wisdom

Making connections with the wisdom of the Māori world is the best way for us to get through COVID-19. We must exercise our rangatiratanga, or the mana of the iwi, which is essentially the power to protect. It is the power to protect our lands, our waterways, our resources, the power to protect our young and old. It was the basic power that te iwi Māori had to look after themselves, make laws for themselves and to keep themselves safe.

Respecting Tapu and Noa

One such law is the law of protection around tapu and noa. In pre-colonial times, the health of the Māori community was protected through tapu and noa. Tapu was the basis of law and order and designated what was safe and unsafe. It was believed that transgression of tapu could lead to mental illness, sickness, physical illness and even death. Noa dictated everyday practices, as a complement to tapu. For example, there were some things that belonged to a certain place and they were not to be moved or mixed with anything else. This separation was necessary to keep people safe. It is similar to why we all stayed home during Lockdown so as not to spread the virus.

Many whānau still follow these laws because they are part of the laws of nature which exist for our safety and wellbeing.