Reading Luke’s Gospel 13:6-17 with Ecological Eyes - Part Six

In the sixth part of the series Elaine Wainwright interprets Luke 13:6-17 showing the importance of the principle of Sabbath for the health and well-being of all creation – human and other-than-human.

Luke 13: 6 Then he told this parable: “A man had a fig tree planted in his vineyard; and he came looking for fruit on it and found none. 7 So he said to the gardener, ‘See here! For three years I have come looking for fruit on this fig tree, and still I find none. Cut it down! Why should it be wasting the soil?’ 8 He replied, ‘Sir, let it alone for one more year, until I dig around it and put manure on it. 9 If it bears fruit next year, well and good; but if not, you can cut it down.’”

10 Now he was teaching in one of the synagogues on the sabbath. 11 And just then there appeared a woman with a spirit that had crippled her for eighteen years. She was bent over and was quite unable to stand up straight. 12 When Jesus saw her, he called her over and said, “Woman, you are set free from your ailment.” 13 When he laid his hands on her, immediately she stood up straight and began praising God. 14 But the leader of the synagogue, indignant because Jesus had cured on the sabbath, kept saying to the crowd, “There are six days on which work ought to be done; come on those days and be cured, and not on the sabbath day.” 15 But Jesus answered him and said, “You hypocrites! Does not each of you on the sabbath untie his ox or his donkey from the manger, and lead it away to give it water? 16 And ought not this woman, a daughter of Abraham whom Satan bound for eighteen long years, be set free from this bondage on the sabbath day?” 17 When he said this, all his opponents were put to shame; and the entire crowd was rejoicing at all the wonderful things that he was doing.

We have just celebrated the first anniversary of Pope Francis’s promulgation of the encyclical Laudato Si’. It has captured the imagination and the profound commitment of not only the Catholic world but all those of the human community who are committed to eco-justice. The encyclical opens with the claim that the Earth “cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted” on it (LS par 2). At the same time, the Pope reminds us that our bodies themselves are made up of Earth’s very elements, particularly air and water. We cannot separate ourselves from all that is material in the world that we share as other-than-human and human beings.

Laudato Si’ has, therefore, participated in the shift in consciousness that is called ecological. What I have been seeking to demonstrate in this series of readings of the Gospel of Luke is that we can and, indeed, we ought to bring that ecological perspective to our reading of this text. It will make us attentive to the human characters in the story and to the range of the other-than-human characters. These are the material elements that are woven through the text. Such a reading will in its turn, spiral back to further shape our ecological consciousness.

Fig Tree and Gardener

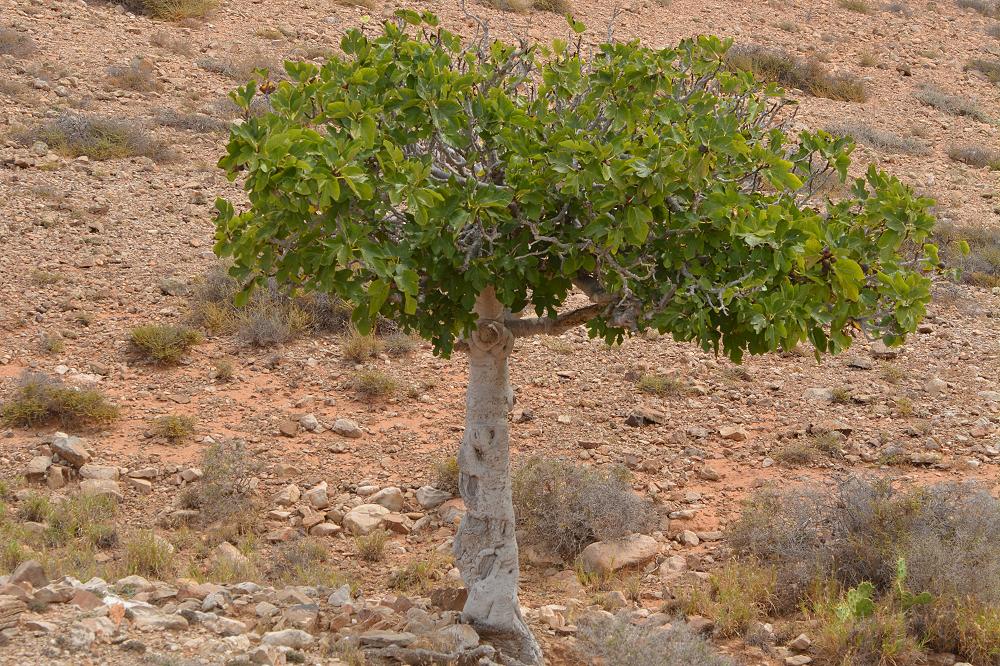

The opening parable in Luke 13:6-9 invites readers into a rich habitat where soil and water, a tree with deep roots and human community co-exist, although with some tension at times.

This particular parable does not begin with the formulaic “the basileia/kingdom of God is like” that gospel readers have come to expect and which they will encounter in Lk 13:18. Rather, the reader is simply invited into the interrelationships within a complex habitat.

The human and other-than-human intersect as the parable opens with a man, a planted fig tree and its fruitlessness. The man’s response to the tree’s lack of fruit is to cut it down because it is wasting the soil — a somewhat violent response. The gardener, the one who tends the tree, digging around it and nurturing it with manure, knows that it is such a relationship between the human and other-than-human which enables the bringing forth of fruit. Readers are invited to hear what it is that the other-than-human speaks.

Disfigurements Seen and Touched

Time characterises the opening of the next segment of text (very explicitly in the English translation in which the connective “de” is translated “now”). It also continues to characterise the opening sentence of this new scene through reference to the “sabbath”. The gospel is located in and must be read in its time context. In this same sentence, that time is linked with space — in one of the synagogues. It is in time and in space/place that the gospel unfolds.

In this space, a woman appears. The Greek phrase used to introduce the woman is kai idou which is a call to attention, to look, to see, to use one’s senses, in particular that of sight. What the reader sees is a woman who has been crippled for 18 years, her body bent over, unable to stand upright.

We are not told the story of the woman’s condition — just the now of her bent-over state. The ecological reader may be drawn to query the woman’s condition and what might have been the multiple environmental factors leading to her present state. Also for such a reader the woman may represent symbolically multiple ecological disfigurements of landscape, of species and within the human community.

The text emphasises that Jesus sees the woman — a dance of senses playing in the space created. It is this seeing that leads to Jesus’ words: “You are freed from your ailment.”

It is, however, only with his touch, flesh on flesh, touching and being touched that the woman is able to stand up.

Healing happens in the materiality of flesh on flesh and gives rise to a voice of praise.

For the ecological reader, this text is one of hope. It points beyond the “bent-over” condition of many of Earth’s elements. We know soil is being poisoned by chemicals used in fertilisation and fracking; air is being polluted by industrial emissions and species are being rendered extinct. It invites engagement in the very process of standing up straight.

Principle of Sabbath Interpreted

The shock for the reader of this text is that there is one who objects to the healing transformation that has just taken place in the body of a woman. The leader of the synagogue, like the gospel narrator, turns attention to time, to the naming of one day each week as holy, as Sabbath, as time of rest for the human and the other-than-human communities. For the ecological reader, Sabbath is a significant principle. It recognises that the Earth itself needs the rhythm of work and rest as do all living beings.

At issue in the encounter between Jesus and the synagogue leader is not Sabbath as a profound principle but whether there are situations when life and the flourishing of life, in the human community and in the other-than-human community, take precedence over the Sabbath principle.

Jesus’ response to the synagogue leader is strong and manifests his depth of feeling in relation to Sabbath. It is grounded in the principle of “freedom from bondage”, to cite the words of Jesus. The Sabbath day frees the human community from work and a bondage to work. It frees the land as well as the animals from over-work. It allows the human and other-than-human communities to rest, to be restored.

The synagogue leader in the Lucan narrative had lost sight of these profound Sabbath principles and had focused only on work or non-work.

In releasing the woman from the bondage that kept her body bent over for 18 years, Jesus demonstrates that Sabbath and the restoration that Sabbath enacts, need to be interpreted and re-interpreted continually in new situations.

The anniversary of Laudato Si’ provides us with an invitation to explore the principle of Sabbath anew in the entire Earth community.

Published in Tui Motu InterIslands magazine. Issue 206, July 2016.