An Ecological Reading of Matthew’s Gospel 15: 21-28

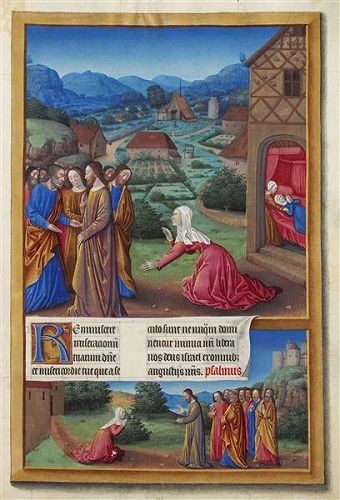

Matthew 15: 21 Jesus left that place and went away to the district of Tyre and Sidon. 22 Just then a Canaanite woman from that region came out and started shouting: “Have mercy on me, Kyrios, Son of David; my daughter is tormented by a demon.” 23 But he did not answer her at all. And his disciples came and urged him, saying: “Send her away, for she keeps shouting after us.” 24 He answered: “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.” 25 But she came and knelt before him, saying: “Kyrios, help me.” 26 He answered: “It is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.” 27 She said: “Yes, Kyrios, yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters’ table.” 28 Then Jesus answered her: “Woman, great is your faith! Let it be done for you as you wish.” And her daughter was healed instantly.

In Tui Motu June 2015, we read the Markan story of a woman named according to her region, Syro-Phoenicia. This woman sought healing for her daughter who was described as “demon possessed” (TM Issue 194, June 2015: 20-21). Now we will read the parallel story in the Gospel of Matthew 15:21-28. We will find that the story has been developed significantly as it was told and re-told in the Matthean context.

Region of Tyre and Sidon

The first words of Matthew’s story draw the reader into its groundedness in time and place, something we’ve come to expect in our ecological reading. The opening reference is vague and time and place merge: Jesus left “that place” (Mt 15:21). We need to go back in the text to discover “that place” was Gennesareth (Mt 14:34) where Jesus carried out his ministry of healing (Mt 14:35-36). However, the text quickly draws us towards a new destination, the region of Tyre and Sidon (Mt 15:21) where Jesus initially refuses to heal.

The reference to the “region” of these two major cities, Tyre and Sidon, along the western seaboard from Galilee, evokes not only materiality but also the tense socio-economic and political interrelationships between the regions.

For instance, one of Tyre’s staple and wealth-producing industries was the production of the precious purple dye. But, as an island city it needed its own hinterland as well that of its most immediate neighbour, Galilee, to supply its inhabitants with food and bread. In Acts 12:20 we find evidence of Tyre’s dependence on Galilee and the conflict it generated. So, complex and tensive material, social and political relationships underlie the brief reference in the opening verse of this text of Jesus going toward, rather than into the region of Tyre and Sidon.

The Canaanite Woman

The ecological reader will be alert to the beginning words of the next verse, kai idou/pay attention or look (Mt 15:22). They draw our attention to a woman, designated as Canaanite, who was coming out of this region, rife withits ethnic and politico-economic tensions.

The name “Canaanite” has puzzled scholars as it seems more symbolic than descriptive, especially when we remember that in the Markan Gospel she is called “Greek, Syro-Phoenician by birth” (Mk 7:26). Her “Canaanite” title in Matthew evokes the ancient inhabitants of the Promised Land who were stripped of access by the Hebrews coming in from the desert. It constructs this woman similarly as being denied access to Israel’s/Galilee’s resources — as will be seen as the story unfolds.

Plea for Healing

The woman seeks healing for her daughter whose body has been possessed by a force or power that she names as demonic (Mt 15:22). We are not told how this possession manifests in the daughter’s body. This can be obscured by the dominating verbal interchange between the woman (who is called Justa in later traditon), and Jesus.

However, the demon-possessed body of the daughter remains close to the surface of the text. As ecological readers we will notice, the corporeality imbedded in the woman’s desire and the supplication for healing.

In Mt 15:24 we encounter the materiality of the other-than-human in the text when Jesus claims that he was sent only to the “lost sheep of the house of Israel”. This phrase occurs only twice in other parts of Scripture, in Psalm 119:176 and Jeremiah 50:6. It speaks of sheep, the most common other-than-human creatures in the agricultural life of the Jewish nation. It is the materiality, the corporeality of the straying sheep that Jesus calls upon to contrast his mission to the lost with the dynastic implications of the title “son of David” given him by the Canaanite woman.

The reference to the lost sheep could be seen or read simply as a literary cipher, but Donna Haraway provides insights into ways in which “the biological and literary or artistic come together with all of the force of lived reality”. This is an area that invites further exploration by the ecological reader of biblical texts.

Embodying Her Plea

Justa continues her agency (Mt 15:25), re-addressing her plea to Jesus. This time, she does not use a title for Jesus. She appeals simply: “Help me.” She uses her body to strengthen her appeal by kneeling before Jesus, as did the leper and the ruler’s daughter earlier in the Gospel (Mt 8:2; 9:18). She is embodying pleas for healing. Justa uses the language of her body to speak her desperate need.

Jesus’ response — “It is not kalon (good or right) to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs” — continues to intertwine the metaphorical and the material. Or, as in Haraway’s words, the “biological and the literary or artistic” come together and the text moves between them.

Sharing Reversed and Extended

Jesus draws “the dogs” into the text to evoke those who ought not share the bread. Justa, however, reverses the function of the metaphor and does even more. Like Haraway, she evokes the “lived reality” of those dogs that found a place beneath the table. That reality was found recorded on a first-century stone of epigraphical remains.

Justa’s reversal of Jesus’ metaphoric use of bread and dogs functions in the text to reverse his response to her desperate plea for her daughter. First, Jesus affirms the faith that enabled Justa to see the possibility of reversal and to bring it to speech: “Even the dogs can eat the crumbs.” And what she desires for her daughter that is also brought about — her daughter is healed instantly and her body is restored. It was Justa’s refusal to accept rejection by Jesus, the Galilean healer within the web of borders and boundaries, that enabled healing to happen.

Reading Scripture Ecologically

To read biblical texts ecologically is to be attentive to the material, the metaphorical, the socio-political, the economic, the human, the holy and other forces that characterise the text and the world it encodes. It is to examine each of these forces in its integrity and then to trace the interrelationships between them. Once again it is to be caught up in habitat, the human, and the holy.

Tui Motu magazine. Issue 217 July 2017: 22-23.

Gallery