A Preferential Option for the Poor

SUSAN SMITH outlines the Church’s preferential option for the poor with a particular focus on those struggling under dehumanising poverty and oppression.

In 2013 Pope Francis stated that “without the preferential option for the poor, the proclamation of the Gospel, which is itself the prime form of charity, risks being misunderstood or submerged” (Evangelii Gaudium, par 199). His words echoed a radical theological insight first articulated in 1968 by Pedro Arrupe, Jesuit Superior General. The meaning of “preferential option for the poor” was to be teased out in the years that followed Vatican Council II.

Focus to Include Justice

The Church has always demonstrated a strong commitment to the poor through its charitable works, but Vatican II’s Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, and the 1971 Synod of Bishops’ statement, Justice in the World (JW), asked Catholics to complement traditional works of charity with works of justice. The Bishops stated that “action on behalf of justice and participation in the transformation of the world fully appear to us as a constitutive dimension of the preaching of the Gospel, or, in other words, of the Church’s mission for the redemption of the human race and its liberation from every oppressive situation” (JW par 6).

In particular, the Bishops recognised that the appalling situation of so many economically and politically disenfranchised demanded a discerning of the signs of the times.

Where should the institutional Church and individuals direct their energies in the face of overwhelming poverty? The answer was that Christians were called to care for all people but by preference they were to choose solidarity with the poor in their struggle for justice.

Liberation Theology Emerges

We cannot underestimate the importance of liberation theology from the late 1960s onwards in exploring the meaning of a preferential option for the poor. Nor should we overlook liberation theology’s emphasis on social analysis methodologies for identifying mission priorities.

Social analysis was a tool that allowed oppressed communities to identify the cause of their problems, so that work for liberation would bring about societal change, not simply band-aid responses to immediate crises. However, Popes Paul VI, John Paul II, and Benedict XVI all registered unease at using social analysis because of its presumed reliance on Marxist class ideologies.

Option for Poor Expanded

During the papacies of John Paul II and Benedict, a preferential option for the poor became much more inclusive. While it still included the economically oppressed, it also evolved to include unborn children, persons with disabilities, the elderly and the terminally ill.

Of course while it is the responsibility of the Church to support all such peoples in their vulnerabilities, the papal widening of what was understood by “option for the poor” weakened the focus on being in solidarity with those struggling to move beyond lives of dehumanising poverty and oppression.

Social Analysis Taught

By the mid-1970s, Christchurch diocesan priest, John Curnow, had introduced social analysis to significant numbers of Māori and Pākehā. Tariana Turia, co-founder of the Māori Party, could say: “I remember in the 70s and 80s, two community champions who had a profound influence on my thinking — the late Father John Curnow, from the Catholic Commission for Evangelisation, Justice and Peace, and Fernando Yusingco who was a Filipino community development worker.”

But how did social analysis touch the lives of those of us who were not Māori? How did it affect the average, white middle-class Catholic, influenced by the teachings of Vatican II, particularly by Gaudium et Spes, by the 1971 Synod of Bishops’ Justice in the World and by the challenging encyclicals of Paul VI, Populorum Progressio (1967), Octogesima Adveniens (1971) and Evangelii Nuntiandi (1975)?

For many of us, social analysis touched our lives through workshops run by Fr Curnow. John organised these for many different groups — Catholic Sisters, peace activists, feminists, Māori, social justice groups, groups focused on colonies struggling against enormous odds to gain political independence such as the then New Hebrides, East Timor, or groups working with anti-Marcos groups in the Philippines — and the workshops were held across New Zealand.

God Has Preferential Love of the Poor

What helped me to appreciate what an option for the poor meant came through re-reading the biblical texts from the position of “the other”.

What were we to make of Yahweh’s words to Israel: “I have observed the misery of my people who are in Egypt; I have heard their cry on account of their taskmasters. Indeed, I know their sufferings, and I have come down to deliver them from the Egyptians, and to bring them up out of that land to a good and broad land, a land flowing with milk and honey” (Exodus 3:7-8).

God’s preferential, not exclusive, love of an oppressed people is abundantly demonstrated. God was not on about upping the benefit by a few dollars a week. God was on about bringing Israel to a good and broad land.

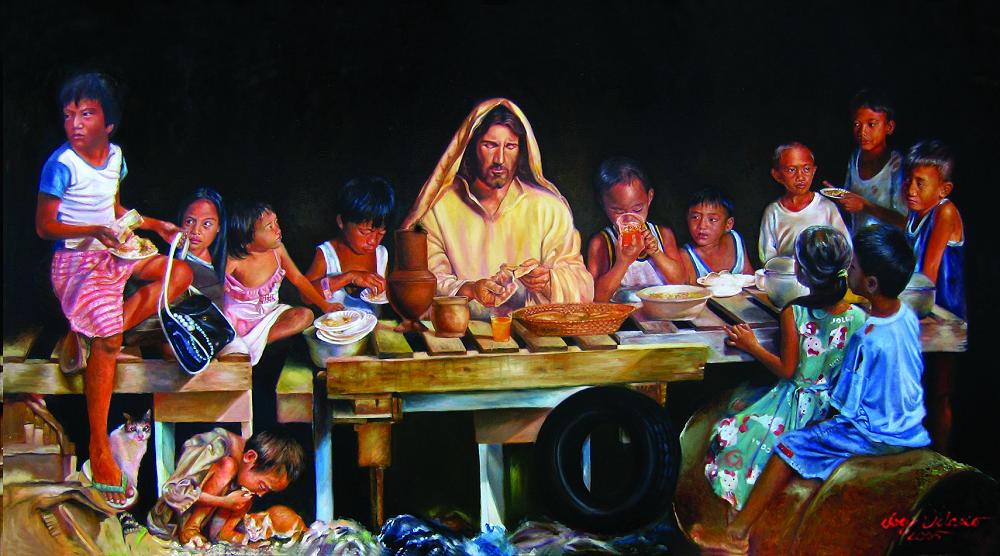

Jesus Makes an Option for the Poor

I was even more struck by a careful reading of the Gospels. Jesus was a village artisan; he chose four fishermen who left their boats and servants to follow him. In other words, Jesus did not belong to the poorest sectors of Palestinian society. Although he said that the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head (Mt 8:20), and although he exhorted the rich ruler to leave all his wealth behind (Lk 18:18-23), it is important to note that Jesus does not praise poverty as such. Instead, he is concerned to help the poor; he feeds the hungry, restores sight to the blind, speech to the dumb and restores people to life. In this way he announces the reign of God and fulfils the messianic prophecies of Isaiah who proclaimed that the Messiah has come to bring good news to the poor (Is 61:1, see also Lk 4:18).

What a thoughtful reading of the Gospels reveals time and time again is that Jesus of Nazareth, who came from what we today might call, the “lower middle class”, reached out in compassion and mercy to those who were further down the socio-economic ladder. But, just as importantly, Jesus denounced those above him on the social pyramid — for the higher up were responsible for the sufferings of those down below. The Gospels depict Jesus confronting scribes and Pharisees during his Galilean ministry — when he reaches Jerusalem, he denounces those controlling temple life. His prophetic denunciation of Jewish religious leaders meant that they complained to Pilate who ordered the execution and death of Jesus.

In the Gospels we see Jesus consciously making an option to come to the rescue of the poor and marginalised in Jewish society. At the same time we see him denouncing those political and religious leaders, so often responsible for the oppressive situations in which others find themselves.

Our Option for the Poor

In contemporary New Zealand, the gap between rich and poor is widening. For example, the CEO of one of our biggest retailing stores earns a base annual salary of $1.4 million, plus a possible bonus of $700,000, while a shop assistant might earn $35,212 in a year. Since 1997, CEOs’ incomes have registered an increase of 228 per cent, or an annual 7 per cent increase. The wealthiest 10 per cent own nearly a fifth of the country’s net worth, while the poorest half of the country has less than 5 per cent (NZ Listener, April 29-May 5, 2017).

Catholics such as those who read and appreciate Tui Motu have a real responsibility to make a preferential option for the poor. It will require us to reach out in compassionate love to those more vulnerable than us, and challenge those higher up the social ladder who benefit from the inequity of existing financial and political structures. We are called to bring good news to the poor by being in solidarity with them as they struggle against injustices.

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 217 July 2017: 4-5