The late Pā Henare Tate gave Tui Motu its name when it was first published in September 1997. In this article, published on the magazine's 20th anniversary, Henare explains the meaning of the name.

"Tuia i runga; tuia i raro; tuia i waho. Bind all that is above; bind all that is below; bind all that is unseen; bind all that can be seen.” The proverb expresses Pā Henare Tate’s title for Tui Motu magazine. It is the stitching together of peoples and lands in God’s creation. The sewing, threading, lacing and binding together again and again of what is cut off or distant. And in the name is the vision, hope and mandate for our magazine.

Pā Henare explained: “We are linked by blood to our whānau or iwi but we are linked to others of different families or races who are on the same journey as ourselves. We encounter them too.

“We are linked also to the land — this is the significance of ‘motu’. Sometimes we think of the separate islands and other times of te motu, the whole land. In terms of our whakapapa, our genealogy, Māori have strong links with the Pacific peoples. And we are linked, too, with those who came here from afar in the last century: their blood is in us.

“Atua/God binds all together. The word ‘tui’ brings this all to mind — the binding, sewing, stitching, bonding. In pre-Christian times the link with God constituted the sacredness and the dignity of our Māori people.

“Through the Gospel Christ was introduced to the whole fabric of Māori belief. We relate to Christ as tuākana, the eldest, the firstborn. Paul calls Christ ‘the first born of all creation’ (Col 1:15) which helps us understand our link, ourtuitui/sewing to God through Christ. We are ‘knitted’ to Christ and knitted to God.

“Our knitting with God can be a process of stretching; a surrender in faith. A piece that is sewn onto a garment has to surrender to the movement of the garment.

“The stitching together of people is also a process of stretching. First the Māori people must be recognised as tangata whenua/people of the land. At the time of the Treaty, the Māori response was tuku, to share their resources. Every time someone is welcomed onto the marae the home people receive the manuhiri who may, or may not, be Māori. The hosts go outside of themselves to receive the visitors, so that they become one with the home people. The title manuhirishould have the shortest “self life” of any, because visitors are straight away invited to belong.

“This is also a Christian concept. Those who are welcomed become part of the ‘body’. This gives people mana. Pain comes where one party abuses the hospitality. The tragedy after the signing of the Treaty was that those who were invited in displaced the welcomers and took over.

“These Treaty issues must be addressed to enable Māori to exercise mana and restore their dignity so they are once again able to share their home. The supreme injustice of depriving Māori of their ancestry and rights has put them in a position of noa, of weakness and powerlessness. Their strength has to be restored so that once again there can be outreach and hospitality towards other peoples.

“The stitching/tui I runga becomes an imperative, stitch! ‘Tuia i te muka here tangata, stitch them with the fibre that alone can knit people together.’ In Māori spirituality the fibre is the Holy Spirit, penetrating land, people and all creation.

“We have to understand Māori concepts, for instance te wa, the moment. Paul’s phrase springs to mind: ‘Now is the acceptable time, now the day of salvation’ (2 Cor 6:2). This kaupapa is all about the moment, the opportunity to restore the people.

“We are at a crucial stage of the journey. We are all in this together. And being knit together means we help one another along the road. If we fail to respond, then we hold people back and we miss the moment, the kairos offered by God. Part of enjoying human dignity is being able to restore and affirm the rights of others.

“At the heart of the process of restoration is recognising the relationship of God and land. It is a violation to sever the link between people and their land. The broken link needs restitching. Tapu i te whenua must be restored to the land so that it has the mana to nourish people. We encounter Atua/God in the land when the indigenous people are respected.

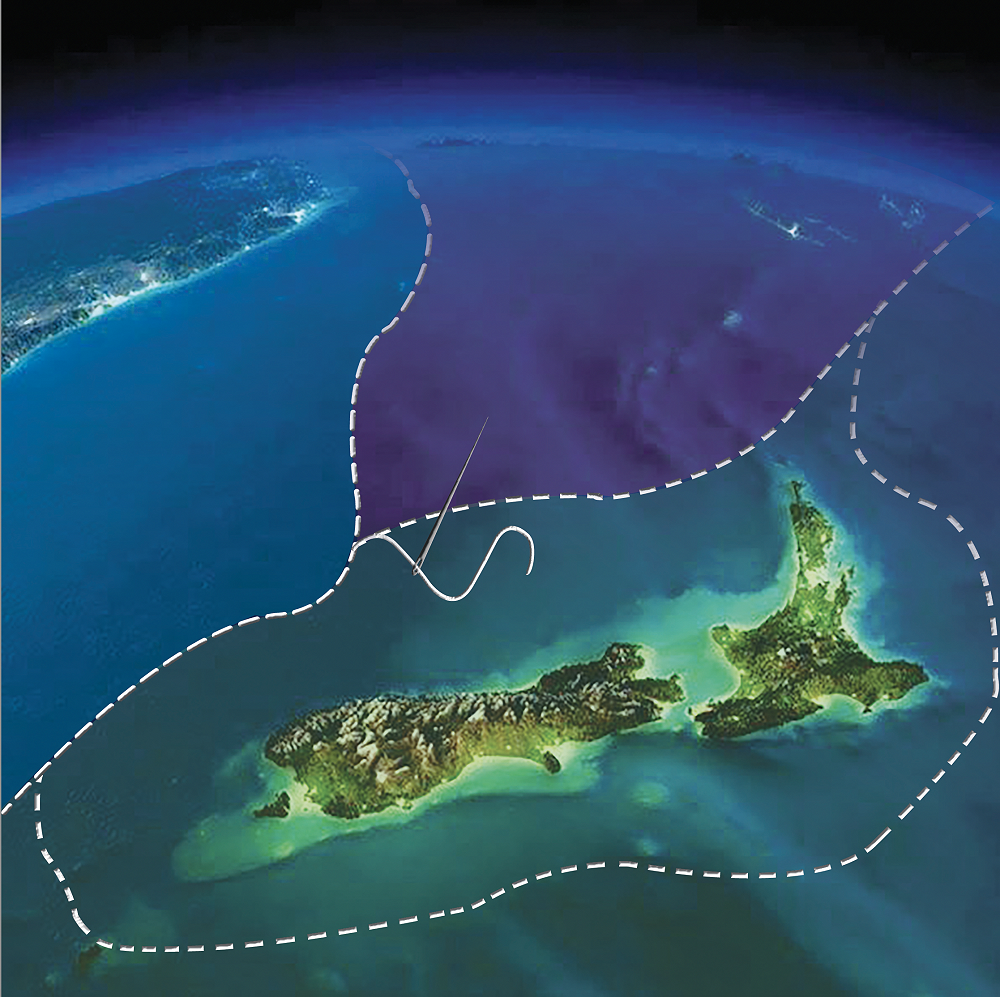

“We can see the linking of the islands and people of Aotearoa in Māori imagery. They speak of those who die going on a journey beginning far south in Rakiura/Stewart Island, or Wharekauri/Chatham Islands; from Murihiku, the southernmost part of the South Island and travelling up the island, crossing Te Moana-o-Raukawa/Cook Strait and then traversing Te Ika-a-Māui/North Island until they arrive at Te Rerenga-Wairua/Spirits Bay.

“The two most important events in our lives are te whānautanga/birth and te matenga/death. In death the spirit retraces the journey and stitches together the land, revisiting each of the iwi until it reaches Te Tai Tokerau and the iwi of the far north who are the guardians of the souls of the departed. In this journey life is brought to completion.”

First published in Tui Motu Magazine Issue 209 September 2017: 3