Famine and Feasting

NICHOLAS THOMPSON shows how the Cathedral window depicts the connection between the widow’s risk in sharing her food and the Eucharist.

At the east end of the medieval cathedral of Bourges in France there’s a stunning collection of 13th-century stained glass windows. Each window illustrates the complex way in which medieval people read the Bible. One, the “Passion Window”, sets the events of Good Friday in the middle of Old Testament stories that medieval biblical commentators read as “types” of Jesus’s passion and death. “Typology” was a way of combing the Old Testament for events and symbols that foreshadowed Jesus. It had precedent in the Bible itself. For example, in Matthew 12:40 Jesus speaks about Jonah’s three nights in the belly of a sea monster as a “sign” of his three days in the tomb. The earliest Christian readers of the Bible took examples like this as an encouragement to look for other “types” of Jesus in the Old Testament — and they found them everywhere. Early Christian typology is often surprising, and sometimes implausible to modern readers whose assumptions are unconsciously shaped by the biblical literalism of post-Reformation Christianity. But exuberant typology made sense to the earliest Christians, and to their medieval successors, because they read the Bible — and, in fact, the whole universe — in a mystical or sacramental way, usually assuming that the richest truth was to be found by taking soundings beneath the surface of the literal meaning.

Some of the typology in the Passion window at Bourges will be familiar to anyone who’s been to the services for Holy Week. For example, around a panel showing Jesus carrying his cross to Calvary, the children of Israel smear their lintels with the blood of the Passover Lamb (top right) and Abraham takes Isaac up the mountain before raising the sacrificial knife over him (bottom left and right).

Widow and Prophet

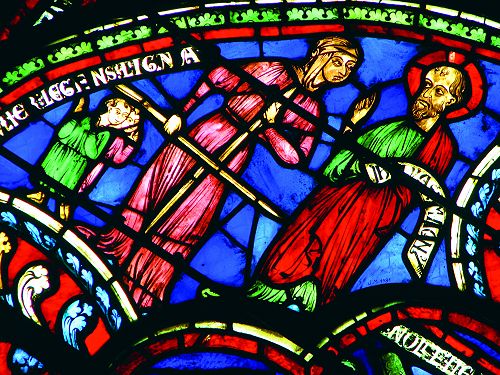

But the top left panel makes a less familiar connection with the Passion. It shows a woman holding two sticks, and she’s talking with a holy man. This panel illustrates the story of the prophet Elijah and the widow of Zarephath (1 Kings 17:8-24). During the reign of the idolatrous Ahab and Jezebel, God punished the land with a drought. Drought led to famine, and Elijah survived for a while at the Wadi Cherith (or “brook of Cherith”). There he had water to drink, and God sent him ravens with meat and bread two times a day. But after a while, the water dried up and Elijah was sent to Zarephath, where God had commanded a widow to feed him. At Zarephath Elijah found the widow gathering sticks. When he asked her for food, she told him that she had only a little flour and oil left to eat. She was gathering wood to bake one last meal for herself and her son, and then she expected they would die. Elijah promised her that if she fed him, God would make the flour and oil last until the end of the drought. And this is what happened: “She, as well as her household, ate for many days. The jar of meal was not emptied, neither did the jug of oil fail, according to the word of the Lord that he spoke by Elijah” (1 Kgs 17:15).

Widow’s Two Sticks

The chapter then describes Elijah raising the widow’s son from the dead in a separate episode, but here I just want to focus on the miracle of the flour and the oil, and its connection with the Passion. The earliest Latin translation of the Old Testament specified that the widow was gathering “two sticks” (duo ligna). Saint Jerome’s (d. 420) improved Latin translation of the Bible (the Vulgate) kept these two sticks. Some modern translations specify two sticks, and others just “sticks”. While it may seem a bit of a leap, the two sticks led Augustine and later medieval commentators to see a connection with the Passion: in their minds the two sticks were a type of the cross. As you can see, this is how the Bourges Passion Window shows the widow holding the duo ligna.

Huge Sacrifice

Despite its poetry, I’m too much a product of my times to see this typology as anything other than fanciful. But Augustine argued that the two sticks pointed to something more basic: that Christian discipleship — taking up your cross and following Jesus — involves a willingness to die, not just figuratively, but literally. Even though the widow knew that she and her son were about to starve to death, she was prepared to feed Elijah in obedience to the command and promise of God. She had no way of knowing that a miracle was coming her way. There’s a sense in which the widow’s faith surpasses that of Abraham depicted further down the window. He was asked to give up the life of his only son. She was asked to give up her only son’s life and her own. It’s true that she expected to die anyway; she and her son only had one meal left. Even so, her sacrifice was considerable. Like a later widow offering her two coins, the widow of Zarephath made a far greater sacrifice in sharing her meal with a stranger than someone who, say, makes a big charitable donation, but isn’t in any imminent risk of starvation.

Risk Worth Taking

This recognition led Augustine, and medieval commentators afterwards, to see the widow’s sacrifice not just as a type of the cross, but of the Eucharist as well. After pointing out the resemblance between the cross and the widow’s sticks, Augustine wrote: “Anyone who wants to receive Christ’s body worthily needs to die to the past and live for the future.”

What he means in this slightly cryptic remark is that, whatever else the Eucharistic stands for, it stands for the risk of death, voluntarily embraced. For most of us food is plentiful, so it’s easy to forget how precarious the supply has been for most of human history. To share food in circumstances of scarcity is literally to say: “This is my body given for you.” In other words, if this food is going to nourish your body, then it’s not going to nourish mine. Your increase is my diminution. Every act of love involves a small diminishment, a greater or lesser death to oneself. The greatest love involves death quite literally (John 15:13), and this seems to be the logic that connects the offer of food with Jesus’s offering of his own life.

Like many comfortable Westerners, I invest a great deal of energy in insulating myself against risks infinitely smaller than the one that faced the widow of Zarephath. However, both the Eucharist and the drama of Holy Week promise that those risks are worth taking: the death symbolised in the sharing of food “becomes for us the bread of life”. Like the widow, none of us really knows how this risk is going to pan out, but we “live for the future” because we have an intuition that the risk is worth taking, even in the face of death.

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 224, March 2018: 10-11.

Gallery