The Word Became Flesh — John 1:1-18

Kathleen Rushton explains how Jesus comes into creation in John 1:1-18 not as a baby, as we read in Matthew and Luke, but as the Word becoming flesh and pitching a tent in us.

CHRISTMAS CAROLS, such as “O Little Babe of Bethlehem,” evoke scenes from the infancy narratives of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. The wonder, lowliness, humanity and vulnerability of the newborn Christ Child inspires cribs, cards, midnight and dawn liturgies and the hearts of millions young and old.

“The Word Became Flesh”

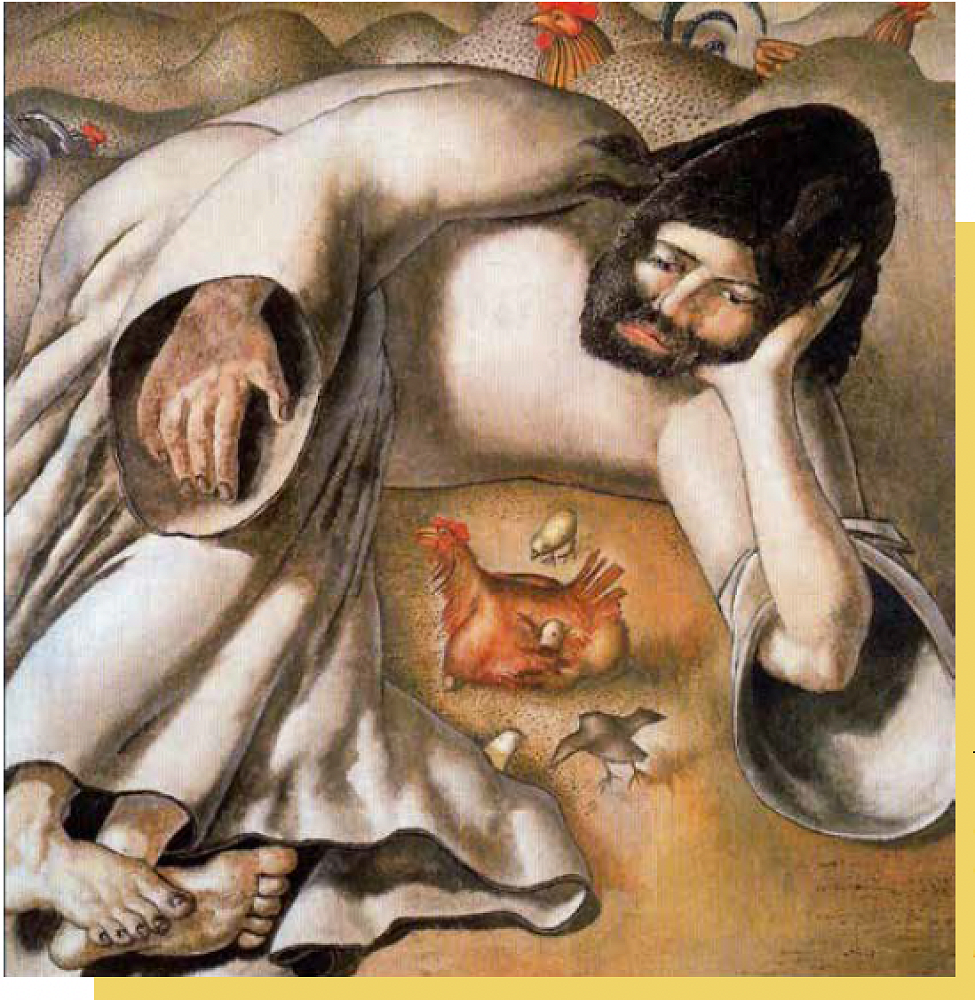

In the Prologue of John’s Gospel (1:1-18) the coming of Jesus is not expressed as a birth. He did not become “a man” in the sense of a male person (aner), or even “a human person” (anthropos). Instead his coming is expressed as “the Word became flesh (sarx) and pitched a tent in us” (Jn 1:14, literal translation).

The Incarnation is not presented as a one-off event to be celebrated only at Christmas time. In John the Genesis creation stories with their ancient cosmologies are reshaped in order to insert Jesus, “the Word became flesh,” into an evolving understanding of the incarnate, dynamic God and the universe.

Sarx — Flesh

The word sarx in John does not characterise humanity as subject to the power of sin nor does it contrast flesh and spirit as found in Paul’s Letters. In John, it emphasises the true humanity of Jesus whom we see tired and thirsty (Jn 4:6-7, 19:28); whose emotion we hear in his voice (Jn 11:33); who wept (Jn 11:35); and whose spirit is troubled as his death approaches (Jn 12:27; 13:21).

“The Word” took on human form and chose the same earthly existence as that of every human person. “Flesh” suggests a human person in the fullest bodily sense including a rational soul. We homo sapiens have evolved with consciousness, imagination, language and religious awareness through a process which required delicate cosmological and geological conditions.

“All Flesh”

While “flesh” refers to human persons as, for example, man and woman are “one flesh” (Gen 2.24–25) and “flesh” is circumcised (Gen 17.11,14), the Word become “flesh” is not limited to humans.

Humanity is not distinct from other living creatures. God’s continuing relationship with creation is with “all flesh.” In the flood, the focus is on “all flesh” (Gen 6:13-22; 7:15-16); the covenant is made with “all flesh” (Gen 9:8–11); God sustains “all flesh” (Ps 136:25); and “all flesh” praises God (Ps 145:21). While “flesh” identifies the incarnation of Jesus with human persons and with all living creatures, there is also difference.

First Difference: Flesh Is Embodiment

Genesis 1 describes God’s creation of the world and of humans as realities that God looked down upon and saw were “good” and “very good.” Through Jesus becoming flesh, the divine enters the materiality of the created world through his body. For those incorporated in Jesus as adopted children of God, the human body is forevermore a valued part of God’s creation uniting the divine and the material.

Our evolved bodies are the bearers of human uniqueness. In our embodied existence, we face the realities of vulnerability and suffering, as well as dependence that is central to our human condition. The paradox of the Word and the flesh is reflected in the divine paradox — the understanding that out of our fragility comes our strength. The tent, a fragile sheet that can be folded up or knocked over, is a symbol of flesh and its vulnerability.

Second Difference: Imago Dei Image of God

God is portrayed as creating humanity in God’s “image” (Gen 1:26, 27). This Imago Dei is associated with reason and intellect and is related to humankind’s dominion in planet Earth. South African theologian Wentzel van Huyssteen says that Imago Dei offers a more holistic way of humanness because it “strongly underlines the sacredness and irreplaceable value of each individual human person [when] seen in the broader context of the imitation of God, the imitatio Dei.” Being created in God’s image obliges us to act in accordance with God’s love — doing God’s creative work in our everyday lives.

Imago Dei relates to humanity’s bodiliness and includes the capacity to reflect on the experience of living — being-in-the-world. Through our body we are interconnected in the universe and through our consciousness/soul we have the capacity to live out our relationship with the Creator.

Third Difference: To Work with God

In some ancient myths, humans are said to be created as workers for the sole purpose of relieving the gods of the burden of labour. The purpose of humans in the biblical tradition is different. Humans are created to work with God. Humans in the image of God are co-creators. Their labour is to love, build and sustain creation but, as we know, humans can also undermine God’s creative activity.

In John’s Gospel there are 28 references to “work” or “working” among which are “completing the works of God” and Jesus or the disciples working in open and public places.

No Body Now but Yours

This understanding of “the Word became flesh and pitched his tent in us” can affirm and challenge us. Pope Francis’s encyclical Laudato Si’ and follow-up Laudate Deum call us to heed and respond to the cry of Earth and the cry of the poor. In John’s language this is the call to “flesh” to respond to “all flesh”.

Francis says it is urgent that we respond as he showed in joining the world’s leaders at COP28. As co-creators we work within God’s complex, evolving, beautiful, suffering and global world.

And recently Francis urged theologians to make a “paradigm shift” in their theologising to “a fundamentally contextual theology capable of reading and interpreting the Gospel in the conditions in which men and women live daily, in different geographical, social and cultural environments.” This recognises that the Word made flesh is known, loved and expressed differently in different parts of the world.

We need contextual theology, Francis wrote, to help bring about change in the Church and the world: “A synodal, missionary and ‘outgoing’ Church can only respond to an ‘outgoing’ theology.”

During the Advent and Christmas seasons we can take to heart Teresa of Avila’s words: “Christ has no body now but yours. No hands, no feet on Earth but yours. Yours are the eyes through which Christ looks lovingly on this world. Yours are the feet with which Christ walks to do good.”

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 288 December 2023: 24-25