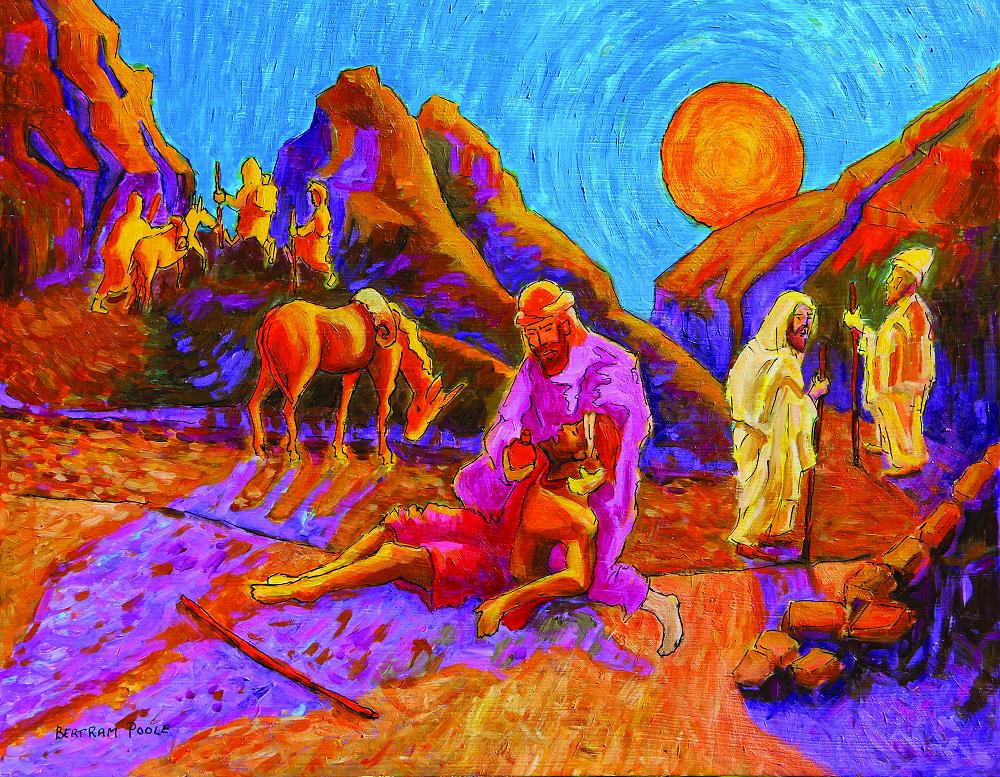

Go and Do Likewise — Luke 10:25-37

Kathleen Rushton points to the radical challenge of the parable of the Good Samaritan Luke 10:25–37 for Jesus's first listeners and for us today.

I was short of cash and suddenly, miraculously, a Good Samaritan leaned over and handed the cashier $10 for me."

"I volunteer with the New Zealand Samaritans. We’re there 24/7 to give confidential emotional support to those experiencing loneliness, depression or suicidal feelings.”

These examples show how we use the phrase “good Samaritan”, which comes from the parable of the Good Samaritan in Luke 10:25-37. But Luke does not call the Samaritan “good”. That addition came about only in the 19th century.

Until then it was known as the “parable of the man who fell among bandits” — the focus being on the injured one. In the 19th century, there was a shift in wealth and influence in European society and the Church. Good people identified with the “good man”, the Samaritan, the one who offered relief — just as they dispensed charity to the poor in their societies. So the focus changed from the wounded one to the rescuer — and the radical significance of the Samaritan was lost. Charitable people became known as “good” Samaritans: those with means giving to those who were dependent.

But parables are puzzling stories — they do not support the way things are or appear to be — and Luke 10:25-37 is no exception. So what can help us to understand the Good Samaritan story today?

The Questions

Interestingly, the parable is framed by questions. The lawyer asks: “Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” Jesus responds by asking him what the Law says. And when the lawyer quotes the commandment, Jesus replies: “Do this, and you will live.” The lawyer asks further: “And who is my neighbour?” Jesus responds by telling a parable to expand his question from: “Who is my neighbour?’’ to “To whom must I become a neighbour?”

The Parable

The parable begins and ends with the person/anthropos who was assaulted. In using anthropos rather than man or woman, the story emphasises the humanity of the person, the human condition.

Jesus’s Jewish listeners knew well the three classes of people serving in the Temple in Jerusalem: priests, Levites and laypeople. The priest, from the highest class, “was going down that road” — returning from Temple duties to Jericho, 27 miles away, where many wealthy priests lived. People were readily recognised by their dress, language and accent. The priest immediately identified a problem — if the half-dead person was not a Jew and the priest touched him, then he would have had to return to Jerusalem for lengthy purification rituals. He passed by.

Then the Levite, from the second class, came riding along and could see that the priest ahead had not stopped for the wounded person. He did not either. Maybe he could not risk facing the priest if he rode into Jericho with the victim.

Now, the listeners would have expected the third person to be a layman — and the one who would act. But no, the hero is a Samaritan, one from a race of people hated by Jews. This turn of events strikes at the heart of religious prejudice and racism.

The Samaritan “came near him . . . saw him . . . was moved with compassion ... went to him.” His compassion goes well beyond what is required by law. He uses all his resources willingly for the wounded person — oil, wine, wrappings, animal, time, energy and money. The listeners might have expected him to drop the person at the edge of the town. But no, the Samaritan risks his own life by taking the wounded person to an inn in a Jewish area of Jericho.

The last scene in the story takes place the following day. Again the Samaritan risks his life by returning to give the innkeeper two denarii — enough to cover food and lodging for about two weeks.

Listeners would have appreciated the risks involved. If the wounded person could not pay his debts he could have been sold as a slave (Matt 18:25). The Samaritan made certain that would not happen. And innkeepers could be disreputable — the Samaritan just had to trust him.

Jesus as the Samaritan

Some early interpreters identified the Samaritan with Jesus, saying that in this parable he was talking about himself. He was a saving outsider, one who did not fit their expectations, one who poured out his love for the wounded, the anthropos. The description of the Samaritan “having a heart moved with compassion” fits exactly how Jesus is described when he sees the funeral of the widow’s only son (Lk 7:13). And the Samaritan’s life-risking action on behalf of the wounded fits the salvation story of Jesus as Christ.

What Could the Parable Mean for Us?

The human condition is as fraught and compromised today as it was in the time of Jesus. We have our own wounded humanity, our own outcasts — and our own fears and prejudices. And we have striking examples of those who reach out, like Jean Vanier who founded the L’Arche communities where those with and without learning disabilities share their lives together.

Or Dr Philip Bagshaw, founder of the Canterbury Charity Hospital Trust, established by the community for the community, where health professionals and people volunteer to provide free services for those missing out on healthcare or on waiting lists.

Be Compassionate Even as We Need Compassion

But the really radical element of this parable is that both the wounded one and saviour are outcasts. The lawyer cannot cope with where he found mercy, cannot even name the Samaritan — instead saying: “the one who showed mercy." The Samaritan acted in the face of rejection and prejudice. The real challenge is to be compassionate even as we need compassion ourselves.

So God’s reign is found in most unlikely people and places — in the unexpected, in the outsider regardless of race or ethnicity. Racism can surface when the religious and racial attitudes of the community are exposed.

The cost and risks taken by the Samaritan point to Jesus. Asking ourselves the question: To whom must I become a neighbour? will cost us. This parable guides us into the works of mercy — into becoming a neighbour. We will see a need and respond with “a heart moved with compassion".

And in a world of structural sin where immense harm is done to vulnerable people through political and economic systems which function to benefit the few, we need to look at the root causes of suffering and injustice, to the works of justice.

We can choose to pass by “on the other side of the road". Or we can cross the road — each person in their woundedness neighbour to another wounded one and the wounded Earth. The ethical demands are boundless.

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 239 July 2019: 22-23