A Leader With a Vision We Can Share

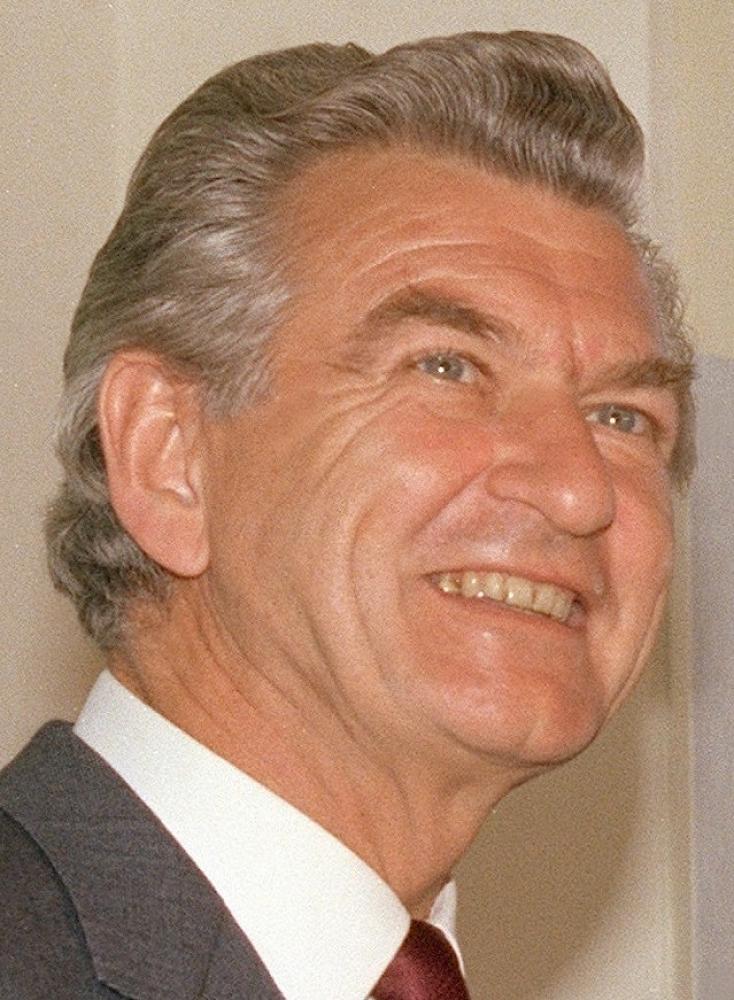

Former Australian Prime Minister Robert James Lee Hawke — Bob Hawke — who led the country between 1983 and 1991, died last month. He was Australia’s most beloved and popular politician. Despite increasing levels of political division, tributes flowed for the 89-year-old from all sections of Australian society and for good reason: Hawke was known to work tirelessly for all.

Perhaps it was his upbringing that made him cognisant of the broad cross-section of people that make up a nation. Born to a Congregational minister and a teacher, Hawke was exposed to people from all walks of life from a young age and over his lifetime lived and worked all across Australia. Such experiences taught him empathy and made him as comfortable in a union meeting or in parliament, as in the pub or at the racecourse.

Indeed, Hawke’s love of beer and sport endeared him to many, and allowed him to reach across political and class divides and rub shoulders with Australians of all stripes. It was a pastime he clearly relished, and made him Australia’s most relatable leader. Stories abound of his personal style — replying to letters he received from children expressing their concerns, and jumping into a stranger’s car asking to be dropped home after a cricket match. He was a prime minister without pretence.

But Bob was certainly more than just an amiable "people person". He was well educated and creative. He introduced Medicare, Australia’s publicly funded healthcare system, to guarantee medical access for all. And he overhauled and modernised the Australian economy to ensure our prosperity and safeguarded social security for the children of low-income families. When he came to office, only 30 per cent of Australians finished school, one of the worst retention rates in the developed world. By the time he left, it had more than doubled.

He led in the region as well, establishing APEC, the Australian Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum, to bind Australia closer to its neighbours. China, Japan, the United States, Russia, and Southeast Asia also found a firm friend in Hawke.

When the 1989 Tiananmen Square student protests were met with government violence, Hawke extended all temporary Chinese visas in Australia and granted permanent visas to 42,000 Chinese. He cried during his speech announcing the decision, displaying a humanity for which the Australian-Chinese community has been forever grateful. His actions symbolised the hopes of Hawke’s Australia: to be a kinder multicultural society that embraced, rather than feared, migrants.

Whereas today some politicians play on race to score cheap political points, there was nothing Hawke hated more than racism. He could not hide his disgust at the tepid international protest against South Africa’s apartheid. As a trade union leader he spearheaded boycotts of the touring Springboks rugby team. As Prime Minister he rallied Commonwealth leaders to commit to financial sanctions against South Africa. Those sanctions were later credited as being decisive in helping end apartheid altogether.

Hawke’s death came just two days before Australians went to the polls to vote for their next prime minister. I hope that highlighting Hawke's legacy and achievements will serve as a challenge to the new government. And that it will offer Australians an opportunity to reflect on what kind of country we want to be. Hawke’s ambitious vision for a kinder country — a kinder world, even — is one we should always share.

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 238 June 2019: 26