Journeying to Emmaus — Luke 24:13-35

KATHLEEN RUSHTON uses two artworks in her interpretation of the Emmaus Story in Luke 24:13-35.

The painting and the icon, two interpretations of the Emmaus story, are separated by nearly 400 years and come from opposite positions around the globe. The painting is from early 17th-century Spain and the icon from 21st-century Aotearoa New Zealand. Each can take us on a different yet similar journey into the encounter between Jesus and two disciples who were slow to recognise that the One they were talking about and to was with them.

It is amazing what we find when we gaze at Diego Velazquez’s painting, Kitchen Maid with the Supper at Emmaus. In the centre a young, black, kitchen maid is at her workbench surrounded by kitchen utensils. She has stopped working. Her full attention and concentration draw the viewer into the picture, into what absorbs her. She leads us to follow the tilt of her head and the direction of her eyes. What has she heard? What has she seen?

Planted in Present Reality

Framed within her picture is another painting, though incomplete, that of the supper at Emmaus. We see the faint figure of Jesus with his hands raised blessing the bread. On the right is a disciple leaning forward and on the left we see only the hand of the second disciple. In a 17th-century Seville kitchen the kitchenmaid looks back. Her scene is juxtaposed with the time and story of the Emmaus supper which we enter through her kitchen and her eyes.

This Emmaus scene captures the moment just before the shadowy figure in the background disappears for: “Then their eyes were opened, and they recognised him; and he vanished from their sight” (Lk 24:31). The kitchen maid represents true faith for she does not see physically as the two disciples did. Yet, she hears the Word of God and believes. Anne Thurston said: “The kitchen maid becomes a symbol for the woman today who reads the scripture with her head inclined towards what was written, listening attentively for the wisdom there, but with her feet firmly and solidly planted in her present reality as she asks: ‘What is the Good News for women now?’”

Planted Firmly and Solidly

An ever-new, reoccurring question arises for people with their “feet firmly and solidly planted in [their] present reality” in Aotearoa New Zealand: What is Good News for people today? Velazquez places a poor, marginalised, black, servant woman at the centre. Maybe she is a bonded labourer or slave. Her position is very different from the two disciples. We might ask ourselves who we would paint at the centre of this scene today and what story our character would tell.

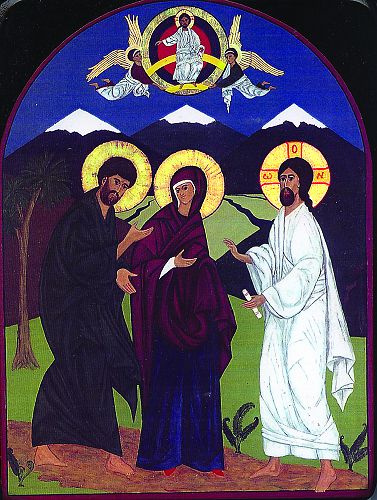

Phil Dyer’s 2002 icon, Meeting Christ on the Way (below) also places a woman in the story by depicting a couple, a man and a woman on the road to Emmaus. This depiction is supported by an interesting convergence between John’s tradition that Mary of Clopas, a relative of the mother of Jesus, was present at the cross (Jn 19:25) and Luke’s tradition that Cleopas was a disciple who was in Jerusalem at the time of the crucifixion (Lk 24:18). Clopas and Cleopas are forms of a rare name found only in these two gospels and in Hegesippus, a 2nd-century writer. Mary of Clopas, then, may well be the wife of Cleopas who accompanied him on the road to Emmaus. Among other husband and wife disciples in the early church are Andronicus and Junia (Rom 16:7) and Prisca and Aquila (I Cor 16:19). Again, we might wonder what story a couple today might tell of their meeting Jesus on the Way.

The icon’s setting is a rural Canterbury landscape. In the background is the snow-capped Torlesse Range from which three rivers flow irrigating the plains. In his explanation of the icon, Phil Dyer points out that the travellers did not perceive the Risen One’s presence but that creation responds with eager expectation (Rom 8:19) “as shown by the fern fronds — symbols of new life — which unfold along the path, and silently invite the viewer to also unfold the moments of hope and grace that are encountered in the course of daily life, sometimes being so close that they are missed in the business or mundaneness of living.”

Now viewing the icon nearly 20 years later we know that creation is responding with eager expectation not silently but in loud lament inviting us to be attentive to the greatly diminished flow and quality of water in the braided rivers and also in the aquifers deep beneath the plains. A front-page article in the Christchurch newspaper The Press (24 Feb 2017) included a map sourced from the Ministry of Environment showing Canterbury rivers colour-coded according to their “swimability”. While the rivers of the high country regions showed the blues and greens of excellent and good, those flowing through the plains showed the yellows and browns of fair, intermittent and poor.

Non-Violent Resistance

Jesus himself lived in violent times. Justin Taylor SM points out that in Roman occupied Palestine, for those first hearers of Luke’s Gospel, “going to Emmaus” would mean going to join those who advocated a violent military option to overthrow the Romans. Usually Jews worked in peacefully with their foreign rulers because, from the time of Jeremiah, they believed that their various situations were part of God’s plan to chastise and redeem Israel. This view changed from the time of Maccabees when some (but not all) Jews, began to support armed revolt. The Battle of Emmaus (166 BCE) against the occupying Greek forces was a significant victory for Judas Maccabeus (I Mac 3:40; II Mac 8:8–29).

The two disciples spoke “about Jesus of Nazareth, who was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people” (Lk 24:19). With disappointment they recount how he was condemned and crucified. They had hoped he was going to be the one to set Israel free (Lk 24:20–21). “Going to Emmaus” suggests they were joining those taking the violent option because they were disillusioned with Jesus who, as Pope Francis reminds us in his World Day of Peace message, “marked out the path of nonviolence.” After meeting, and later recognising Jesus, the two disciples returned to Jerusalem and found the 11 and their disciples (Lk 24:33).

So we journey reading scripture with our head inclined towards what was written, listening attentively for the wisdom there, but with our feet firmly and solidly planted in the present reality of Aotearoa New Zealand. We can ask: “What is the Good News for people now?” At times we might be like the two confused, puzzled disciples journeying away from Jerusalem and then meeting the Risen Jesus unknowingly (Lk 24:15), the same Jesus we meet so often unknowingly. In the Emmaus journey as in our journey, we traverse a range of emotions: sadness, disappointment, confusion, gloom, bewilderment, blindness and suspense, as well as discovery, hope, joy, dawning recognition, care, non-violence, empowerment and excitement.

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 214 April 2017: 24-25.

Gallery