Funerals and Mourning

Peter Lineham discusses the changing views on death and mourning in Aotearoa New Zealand.

I have been to a rash of funerals recently. Long ones, short ones, religious ones, secular ones, and ones that I found it difficult to classify (does a short reading from the Bible make it religious, I wonder), with secular celebrants, ministers, priests, bishops, some in Catholic churches, some in Protestant churches, and some in funeral homes. The sheer variety is startling.

Funerals Were Church Domain

Funerals have changed radically in the past 50 years. Until the 1970s funerals were almost entirely the preserve of churches, and the variations in funerals were simply reflective of the different theologies embraced by churches about death. There was a Catholic version and a Protestant version, but almost always funerals were religious.

In fact, funerals were the last place where religion persisted, after church-going, baptisms and church weddings had gone into terminal decline (if you pardon the inappropriate metaphor).

Funeral Services Privatised

Today, however, death is run by funeral directors. Traditionally the funeral director was the humble undertaker (usually the local cabinet maker), and did little more than furnish the coffin. Now, funeral directors advertise their services, and provide whatever type of service the family may choose, from religious or secular, employing suitable funeral celebrants. Since Covid it is even common to hold no funeral at all.

Catholic requiem Masses are reserved for the “really religious”, while Protestant services are often designed by the family, and that means that the favourite music of the deceased — however inappropriate — accompanies the coffin on its departure to burial or cremation. In the past everyone wore a black suit or dress, set aside for funerals, but now the dress code is more casual.

Above all the eulogy has spun out of control, often including humorous reminiscences celebrating the life of the deceased, despite formal guidelines for Catholic funerals disallowing eulogies until after the Mass or at the vigil. The slide-show of the person's life is now standard. Only the sandwiches at the after-function seem to have gone unchanged (although some Catholics would have been used to wakes)!

Move from Fear-Invoking Funerals

These trends partly reflect the secularisation of rituals, but there are other factors at play. The so-called “Victorian way of death” reflected a society with shocking rates of untimely death, but also a longing for personal solace, reflecting the very troubled spirit of the Victorians, for whom death seemed profoundly disturbing. Dying was painful and often prolonged, and Victorian funeral services would invariably recall the last hours of the deceased. Readers of Dickens will be familiar with the pattern.

In the grim rituals, concern with dying and what lay beyond death was always present. Staunch Protestants had heard many a sermon on the grim doctrine of eternal hell for unbelievers.

Catholics had a deep fear of Purgatory. Such fears are quite rare today, even though the doctrine behind them remains in some theologies.

Catholic Last Rites

For these reasons, Catholics were very anxious to receive the last rites, Penance, Extreme Unction and the Viaticum (Communion). Today, though, Extreme Unction, renamed the Anointing of the Sick, is seen as appropriate for the sick as well as the dying. Back in the 12th century the rituals of Extreme Unction had evolved into a sacrament that only a priest could administer.

Protestant Profession of Faith

Protestants had no sacrament to prepare for death, although a dying profession of faith marked out a “good death”, and it was not unknown for strong religious pressure to be visited on the dying.

Funerals Adapted

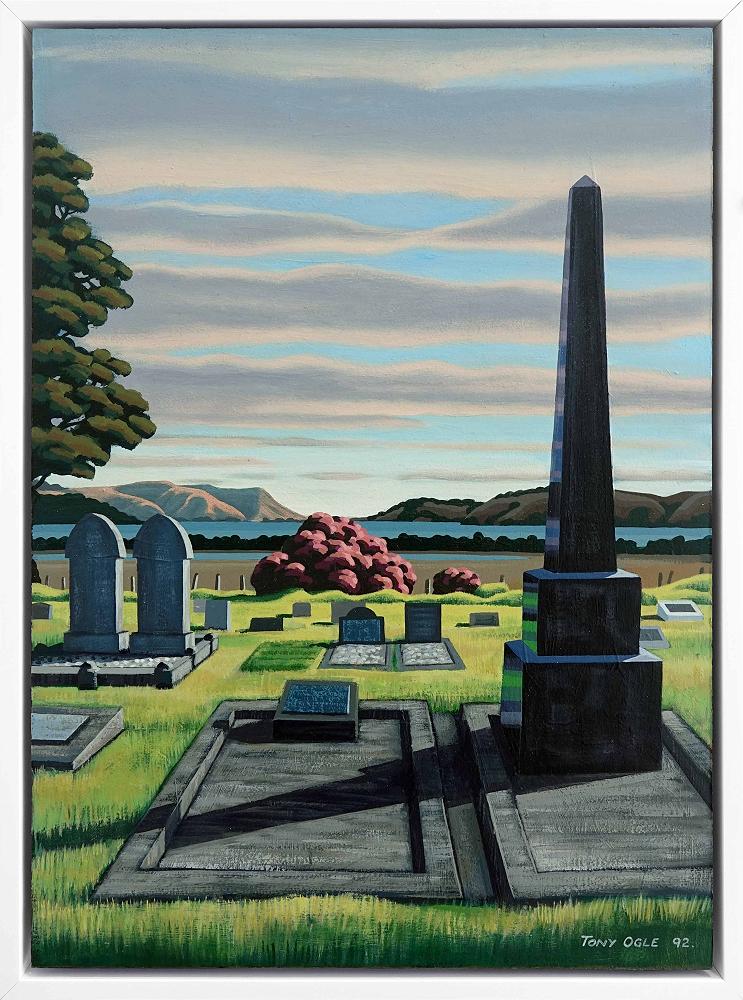

The early New Zealand settlers modified these patterns somewhat, for migrants found that “It was hard to die frae hame.” Death was hard, and migrants felt that burial in a strange land was a grim conclusion to life.

In New Zealand there was a widespread revulsion at the Calvinist emphasis on eternal hell. Funerals were used to remind Pākehā of the afterlife, the hope that something lay beyond death.

The grimness of the First World War, where so many soldiers died and were buried far from home with little opportunity for the ritual of the funeral, upset the equilibrium of the Victorian approach to death and the space to mourn when no funeral was possible.

Hiding Death

We are much more able to hide death away today. The hospice movement, dating back to the 1970s, eases the experiences of the dying, but also conceals death, softens it and calms it. Outside the hospice, the focus is on living, with very little talk of individual recognition of our own mortality.

A curious feature of the New Zealand funeral is the standard practice of embalming, perhaps because family and friends will usually view the body. It may also reflect the long delay sometimes between the death and the funeral. (We have not adopted the British practice of an early funeral and a memorial service a month later).

Benefits of Tangihanga

Often people remark on the Māori approach to death, with the length of tangihanga, the very public displays of grief, the use of greenery wreaths and the time spent around the open coffin, until the moment of the funeral service.

Tangihanga have changed, too, for example using photographs, which was once quite unacceptable, as aids to memory. The practices of Māori and Pākehā have drawn together somewhat, with some Māori elements evident in some Pākehā funerals.

Changing Attitudes

There are broader issues which underlie these changes. New Zealand was among the first states to abolish capital punishment in 1961, reflecting a greater respect for life, perhaps, but New Zealand has also been among the countries which have legalised euthanasia, albeit in somewhat restricted circumstances.

The way we deal with suicide has also changed, with much greater sensitivity towards the deceased, as a victim rather than a sinner.

The advent of cremation has often been related to the lack of space in cemeteries, but another factor is the squeamishness of those who remain at the thought of the processes of the decomposition of the corpse in the ground. It was only in 1963 that Catholics were permitted by the church to be cremated, but in 2016 Pope Francis reminded Catholics that ashes ought not be scattered or kept at home.

Fear of Death

For all these changes, anxiety about death seems greater rather than diminished. The issue may no longer be the pain of death, but fear and nervousness remain.

Surveys suggest that these fears are stronger for the person isolated from family and with no children to maintain the genetic line; surveys also suggest that fear is stronger for females and for the young. In an odd, ironical twist, religious people seem more nervous about death than the irreligious, perhaps because they know more is at stake!

The weird experiments with refrigerating bodies until the elixir of life is found, suggest that Western culture is deeply attached to the idea of personal immortality, even in the midst of widespread discomfort with religion.

Funerals to Celebrate the Dead and Life after Death

I wonder what the role of faith and the church will play in the future of death. One reflection of this is the funeral service in the New Zealand Prayerbook of the Anglican Church, which takes a generous attitude towards the future of those who have passed away and speaks words of careful consolation to the living.

I would guess that most of us are content with refocusing funerals on thanksgiving for the life of the person who has passed away, but Christian faith also declares its distinctive hope of eternal life in God, life in a newer and richer dimension.

The funeral is in some ways the clearest evidence of the ways in which our values diverge from those of our society.

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 298 November 2024: 4-5