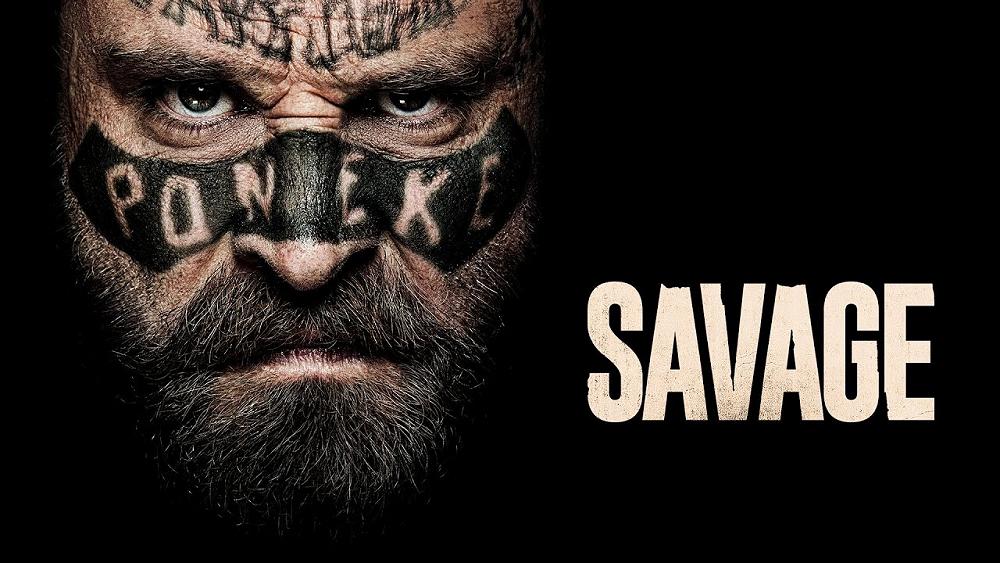

Savage

Directed by Sam Kelly. Reviewed by Paul Sorrell

In many ways a Once Were Warriors for the 2020s, Savage traces the gruelling journey of one man from a life of unrelenting poverty, deprivation and violence to the tentative beginnings of redemption.

We first meet Danny — familiarly known as Damage — at a gang party in 1989. As “sergeant” or enforcer to the boss of the Savages, Moses, he is at the top of the tree in the brutal gang scene. Damage is about to execute a “hit” on a fellow gang member who has transgressed the group’s strict code of ethics, an event that will change his whole world.

A flashback to 1965 illuminates the origins of their friendship. Removed from his poverty-stricken Pākehā home for stealing food from a neighbour’s house, Danny is placed in a boys’ remand home. Between bouts of savage beating and paedophiliac fondling from staff members, he forms an unbreakable bond with his Tongan room-mate, Moses.

The film then pulls us into the 1970s where the two young men are thrust into New Zealand’s developing gang culture, where Danny has a violent confrontation with his brother Liam. Forcing himself to cauterise family bonds, Danny cements his mana by giving his loyalty to the Savages and their leader without reserve. But in his role of violent enforcer, not just against external enemies, but against threats arising from within, Danny/Damage inevitably faces challenges to his authority, and also to his residual sense of humanity.

The pull of his birth family never leaves him. Every year Danny doggedly travels country roads to his backblocks home, but never gets further than the gate, where he scores the wooden fence as a memento of yet another frustrated visit.

Despite its deep dysfunction, Damage’s world has its own rationale. Moses glories in the fact that he and his associates are “animals”, obeying the unforgiving logic of a world red in tooth and claw. The “normal” world, where people own flash cars and nice houses, merely gilds this Darwinian reality with a veneer of respectability.

Savage is not for the faint-hearted — every scene is like a punch in the guts. Yet we are offered some crumbs of hope. At the end of the film, Damage is in freefall. Only when he realises that a young prospect will become exactly like him does he get a glimpse of the boy he might once have been and begin the painful journey away from the only world he has known.

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 253 October 2020: 28