Truth Hidden by Silence

Richard Shaw tells the story of how his family acquired land confiscated from Taranaki Māori.

There’s a pretty good chance that my great-uncle, Dick Gilhooly, a secular priest who was ordained in the old St Joseph's Cathedral on Buckle Street in Wellington, might well have written for one of Tui Motu’s historical predecessors, the New Zealand Tablet. At the very least, he would have read it closely.

But whether as writer or reader, I think it unlikely Dick would have been much detained by the family history sitting behind him. Indeed, by the time Dick was ordained in 1933, his family background had long since fallen into the realm of the unspoken and the forgotten.

Researching Family History

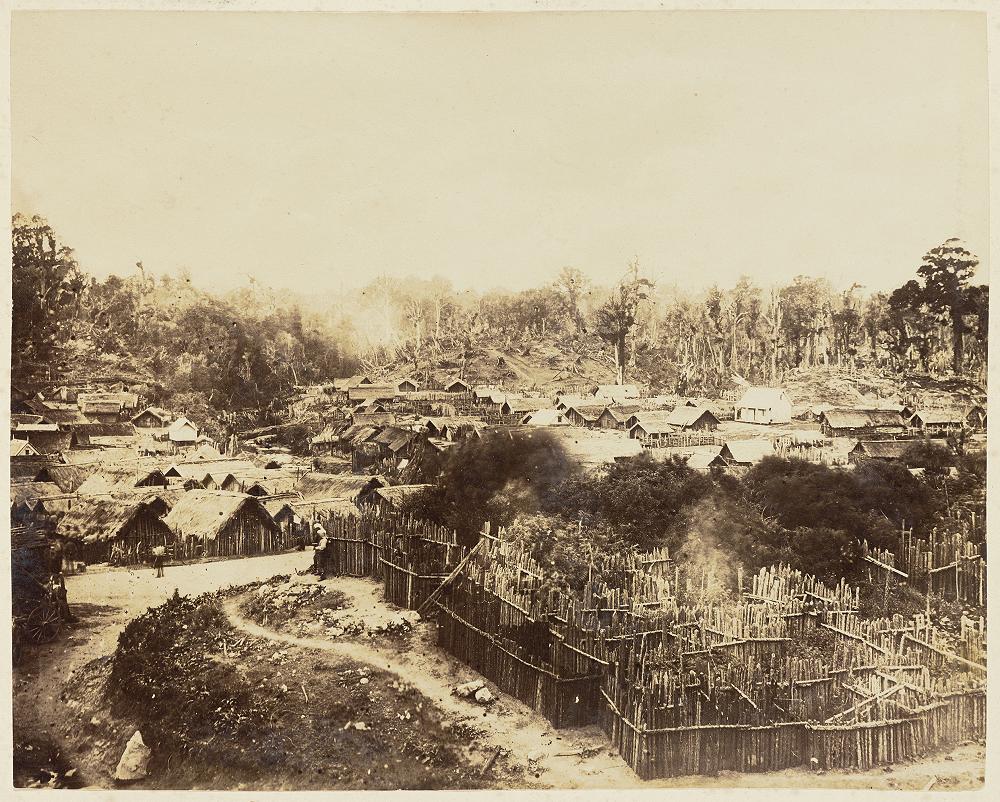

Recently, I have begun trying to haul it back out into the light. As far as I can tell, the central bits of the story go like this. Dick’s father, Andrew Gilhooly, was one of the 1,589 men who invaded Parihaka on the 5 November 1881. A member of the Armed Constabulary’s (AC) No. 3 Company from 1877–1886, my great-grandfather remained at Parihaka as part of an occupying garrison until late 1884.

Historian Rachel Buchanan (Taranaki, Te Ātiawa) has pointed out that Parihaka is not just an invasion day story, although I doubt I’m the only Pākehā to have been taken aback upon discovering that it is also an occupation story.

Constabulary Occupation of Parihaka

The occupation was not benign. First came the weeks and months of despoliation as the colonial state’s agents — my great-grandfather included — set about annihilating the village and its hundreds of acres of cultivations. Then came the years of restrictions, especially on the movement of people into and out of Parihaka.

Sometimes the non-violent resistance from mana whenua got a bit much for the AC. The parliamentary record reports that on 17 April 1882, No. 3 Company men broke up an attempt by “Strange Natives” to distribute food at the pā. Native Minister John Bryce found the idea of Māori taking supplies to starving people in Parihaka to be “in every way objectionable”. And so, in retaliation for “this act of antagonism to the expressed orders of the Government” the AC pulled a dozen whare down (this on top of the 250 they had destroyed in late 1881) — although their commanding officer thoughtfully ensured that “everything [was] removed out of them first.”

Family Farm on Confiscated Land

Having participated in the military campaign against Parihaka, Andrew was back nine years later as part of the agricultural campaign to complete the alienation of Taranaki Māori from their land.

In 1895 he gained freehold title to a farm that had once been part of Parihaka’s extensive cultivations.

In 1902 he leased a second farm that was part of the pernicious West Coast leasehold system (under which control of Māori land was vested in the Crown’s Native Trustee, and perpetual leases — many of which are still in force today — were given to non-Māori farmers). And in 1921, Andrew’s wife Kate purchased her own property, one the colonial authorities saw fit to call Parihaka A.

Error Favoured More Confiscation

A couple of quick things about those farms before moving on. On the Taranaki coast confiscated land on the seaward side of the South Road (an invasion road running from Ōpunake in the south to Ōkato in the north) was usually available for freehold purchase, while farms on the mountain side were generally reserved for West Coast leases.

Bizarrely, a surveying error meant that the South Road ended up being closer to the mountain than originally planned, such that 5,000 additional acres of land on the seaward side were available for sale and settlement.

My great-grandfather’s first farm was part of that tranche.

Confiscation as Further Punishment

Moreover, in 1882 the Crown decided to hold back a further 5,000 acres from any future reserves as “an indemnity for the loss sustained by the government in suppressing the Parihaka sedition” (the one that had been pacific, non-violent and whose protagonists had welcomed my great-grandfather and his AC comrades into Parihaka with gifts of food).

The second and third of the Gilhooly farms, one of which my mother grew up on, accounted for 302 of those 5,000 acres.

Facts of Land Confiscation Buried

Perhaps unsurprisingly, virtually none of this detail found its way down through the years to me. I know lots of stories of my family’s years on the Taranaki coast, but none include the detail I’ve set out here. As far as invasions, occupations and the state’s theft of people’s land is concerned, I grew up in silence.

Forgetting Not the Answer

For a bunch of reasons set out in detail in my memoir, The Forgotten Coast, I’ve been spending a lot of time lately reflecting on this. For what they’re worth, here are some elements of that thinking.

The first is that silence (and its companion forgetting) allows us to put to one side inconvenient truths.

In The Mirror Book, Charlotte Grimshaw notes that “[i]f anything went wrong they had to suppress it, move on, pretend it didn’t happen.” She’s talking about her parents, but the observation could equally apply to Pākehā like me, who narrate settler family histories which polish up the bits about hard work, fortitude and building a new world but swerve around the history that came before (in my case) the purchase of the family farms.

Moreover, although forgetting is generally associated with loss, allowing certain family stories to fall out of the repertoire means you get to gain stuff.

In my case, not remembering the history described above means I get to avoid having to confront the fact that my family cast off its Irish tenant farmer identity and remade itself as a land-owning settler family on the basis of land taken from other people.

Not remembering means not having to confront the paradox that my great-grandfather was born on Irish land that had been confiscated by the English but died in possession of whenua confiscated from Taranaki Māori.

Not remembering means that I get to claim my part in the farmers-are-the-backbone-of-the-nation story without having to question where the Gilhooly farms came from.

I grew up being told that nicking people’s stuff is an offence against the Commandments, liable to land you in hot water after your death. But taking possession of land taken from others through acts that are legally cleansed by the colonial legislature is probably not going to produce the same outcome, because by then it is called settling, not stealing.

Legalising the disposal of confiscated land is a secular form of the sacrament of confession, whereby the slate (or state) is wiped clean and things can begin anew.

There’s a pretty good chance that my great-uncle, Dick Gilhooly, did not give a lot of thought to any of this. But Dick’s past is another country.

Rachel Buchanan is right when she says that “people have to work hard not to know, not to recall, not to see, to be truly ignorant.”

They also have to work hard to know, to recall, to see and to be cognisant of the real history of this land. It has taken me 57 years to realise this, but now I, too, would like to end the forgetting.

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 270 May 2022: 6-7