Jesus Washed Feet — John 13-1-7

KATHLEEN RUSHTON interprets Jesus’s action in John 13:1-17 as introducing a new ordering of relationships.

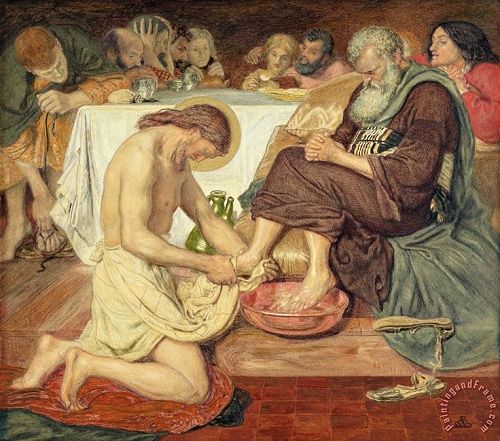

In his painting, “Jesus Washing Peter’s Feet” (1852–6) the English artist Ford Madox Brown captures the Fourth Evangelist’s characteristic way of telling the story of Jesus through vivid, concrete images that embody the Word made flesh (Jn 1:14). Jesus does not talk about serving. He washes feet.

There is a back story to this remarkable painting. Brown’s original version caused outrage. Critics were offended by his coarse depiction of Jesus nude to the waist and with his leg exposed. The painting remained unsold for several years until Brown retouched it several times and clothed the figure of Jesus in green robes. (He painted the scene again in watercolours in 1876.) Brown’s original inspiration, however, peeled away layers which obscured the ancient context (world behind the text), the radical Jesus of the Fourth Gospel story (world of the text) and the transformation we are called to today (world in front of the text). Holy Thursday/Maundy Thursday offers an opportunity to look anew at Jesus’s astonishing action and his example to do as he did.

The Slave Does Not Have a Permanent Place

The Fourth Gospel was written in the 90s, somewhere in the Roman Empire, which was then undergirded by the system of slavery. If written in Ephesus, it came from the “hub” of Roman slavery. Slaves were brought from Asia Minor (modern Turkey) and Syria to the statarion, the slave market of Ephesus where they were auctioned and transported to places of demand, especially Rome. The focus of the auction process was a raised wooden platform. At the direction of the auctioneer, the naked or almost naked slave — sometimes wearing a placard describing his or her notable features — stepped up onto the platform to be scrutinised by potential buyers. Spouses could be sold to different buyers. Children could be sold separately from their parents.

All slaves (douloi) were the property of their “lords” (kyrios) who bought them. They had no rights. Children born of slave or owner-slave unions became the property of the owner and like all slaves were included in inheritances to the next of kin. At the order of their owners, slaves could be beaten, chained, imprisoned and even crucified. Any task could be assigned to them including the lowly task of washing soiled feet. At the master’s whim and with but a moment’s notice, slaves could be sold. The words of Jesus highlight the precariousness of a slave’s position in a household in contrast to that of a son (Jn 8:35).

We have a new perspective of slavery when Jesus is portrayed as the Lord (kyrios) who washes the feet of his slaves (douloi, Jn 13:4-6) to whom he gives the status of friends (philos, Jn 15:12-14)

Context of the Supper

The Evangelist tells us that choices had to be made about what to include in this gospel story (Jn 20:30-31; 21:25). This implies a process of selection: how to tell the story and how to order the story. The foot washing is clearly central to the supper (Jn 13:4; 13:23-26). Things are going on here at many levels.

Usually, foot-washing was done on arrival; yet we are told that “during supper Jesus ... got up from table” (Jn 13:2-4). Assuming the appearance of a slave, he “took off his outer garment” (ta himatia), stripping down to his waist cloth, wrapped a towel around his waist and began to wash and dry his disciples’ feet. Jesus’s freely disrobing himself links foot washing with his forced disrobing at his crucifixion when Roman soldiers “took his clothes” (ta himatia Jn 19:23). Crucifixion was considered a fitting death for a slave.

An Act of Friendship

Jesus’s commandment to love one another as I have loved you (the mandatum Jn 15:12-13), is expressed in his example of foot washing (Jn 13:15), an act motivated by love. We find this no where else in ancient literature. Jesus is not called “friend” explicitly in this Gospel. His life, however, is the incarnation of the ancient ideal of friendship concerning love and death (Jn 15:13; 10:11). This ideal is described by Plato and Aristotle as the love which leads one to lay down one’s life for friends. According to Plato: “Only those who love wish to die for others.” The disciples are to imitate Jesus, wash one another’s feet and to carry out his love commandment — even to the point of laying down their lives for others as Jesus does (Jn 15.13).

The washing of the feet may be understood in three ways. First, one person is subordinate as in a master-slave relationship. This imbalance lingered in the washing of the feet on Holy Thursday. The 1956 Roman reform turned the washing of the feet into a clericalised, hierarchical, male-centred sacred drama — something it had never been. Earlier Christians had washed one another’s feet (Mandatum Fraterum), those of guests, and the feet of the poor (Mandatum Pauperum). Further, uncritical appropriation has led to sincere church-talk about so called “servant leadership”, which theologises away and obscures ancient slavery, a practice which was intrinsically oppressive and maintained only for the benefit of the privileged slave owners.

Second, foot-washing can be understood as freely done, as in a mother-child relationship. One person remains superior. In the idealised image of Mother-Church and her children-members the latter are regarded as eternal infants. Unlike real mothers and real children, Mother-Church’s children are often not encouraged or expected to grow up.

Third, foot-washing may be an action of friendship based on equality. It seems Peter knew all too well that accepting Jesus’s footwashing would mean a whole new way of transformative relating and he was unwilling. Jesus uses the word doulos (slaves Jn 13:16) and does so again in the farewell discourse with a different nuance (Jn 15:15). In this Gospel, Jesus never uses the term “disciples” (mathētai) for his followers. Only in Jn 15:15 does he address them by the term “slaves” which he transforms to “friends”. Translations which in Jn 15.15 and Jn 13:16 have doulos as “servant/s” — the translations on which the servant leadership motif is based — sanitise and obscure the master-slave relationship which is inherent in the foot-washing and the slavery of the text.

I Have Set You an Example

Brown captures so well the shock and dismay of Peter and the disciples. How would the Christians of Ephesus and the Empire have heard this story? Were some slaves? Others slave owners? They knew the reality of slavery and the cultural value of friendship — both expressed in the flesh of Jesus. What is my response to the example of Jesus? I am implicated in a global lifestyle which demands cheap clothing, goods, services and food produced by millions of persons of all ages held in human slavery, including an estimated 800 in Aotearoa New Zealand. Jesus’s example makes flesh/incarnates a whole new order of human relationships and self-giving. How is his foot washing calling me today as friend to participate in Jesus’s work of transforming relationships, whakawhanaungatanga/making right relationship with God, the Earth and people in Church and the world God so loves (Jn 3:16)?

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 224, March 2018: 22-23.

Gallery