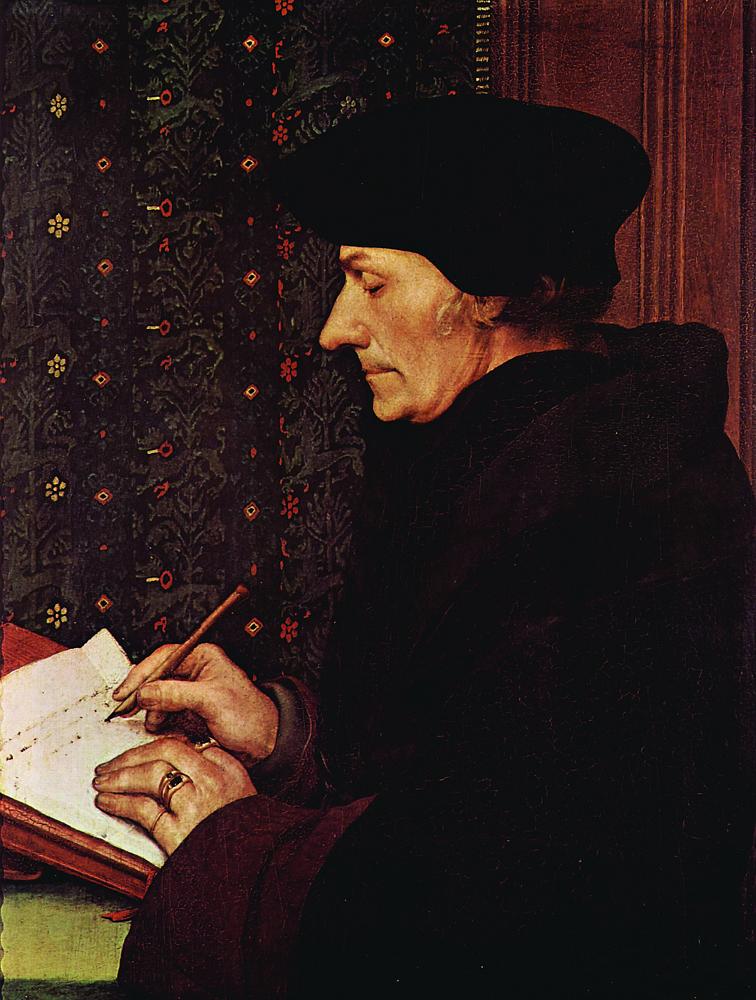

Erasmus: Iconic Figure with Star Allure

PETER MATHESON introduces the Dutchman, Desiderius Erasmus as a visionary reformer and contemporary of Luther but who stayed with the Catholic Church.

The spotlight will be on Martin Luther this year as it is 500 years since his 95 Theses about indulgences sparked off what we often call, rather carelessly, the Reformation. But movements for reform have always been part of the Church’s history. The great monastic movement of the Early Church was launched in a desire for renewal of Christian life. Perhaps the best known of all reforming waves was that of the Franciscans and Dominicans reaching out to lay people in the 13th-century cities. We need to see the Augustinian friar, Martin Luther, in the context of these ongoing reforms. That’s why historians these days speak of a multiplicity of 16th-century reformations — Catholic, humanist, communal, Lutheran, Reformed and Radical. In fact, the Church around 1500 throbbed with reform movements of many kinds — lay, monastic and clerical.

The culture of the 1500s was unbelievably different from ours today. At that time the influence of the Church permeated life in a way we cannot begin to imagine. Warm, personal piety was expressed in countless manifestations including pilgrimages, the celebration of saints’ days and Marian festivals and above all, in the sacraments and devotions which accompanied every moment of individual and communal life from birth to death. Some felt the problem was not a lack of spirituality but a surfeit of it. Certainly that was the view of Catholic reformers such as John Colet, Dean of St Paul’s London; Thomas More, famous for his fraught relationship with Henry VIII; and the superb classical scholar, Erasmus.

Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) stemmed from the Netherlands but his work had a truly European resonance. He was an iconic figure with star allure. To receive a letter from him — and his web of correspondents was huge — was a coveted distinction. Often his letters went straight into print. You won’t go far wrong if you imagine enthusiastic teachers, lawyers, priests, monks and nuns from Spain to Hungary sporting a lapel badge: “I love Erasmus!” A superb Latin and Greek scholar, Erasmus symbolised for thousands of laymen and women, as well as clergy, the need to get back ad fontes, to the sources. By this he meant to study the writings of the Early Fathers and above all the Bible.

In many of the courts, cities and monasteries of Germany, Italy, France and elsewhere, little groups or sodalities gathered to discuss his writings — rather like today’s book clubs. As Erasmus’s writings were in Latin we might be tempted to dismiss these gatherings as élitist but their members were the opinion-makers of the age; advisers to princes, city clerks, merchants, teachers, students and poets.

One of Erasmus’s greatest achievements was the brand new edition of the New Testament in 1516 — going back to the original Greek. Luther profited from it, as did biblical scholars throughout Christendom. Erasmus was alive to the potential of the new printing press to make available to the growing literate class, outside the universities, new editions of the works of Augustine, Jerome and the Cappadocian Fathers. He felt most at home in the printing press of friends such as John Froben, of Basel.

Erasmus was no mere scholar, though. He had a vision of a less cluttered Church and of a spirituality that gave worth and dignity to daily life, to the personal and communal work and relationships of ordinary people. He thought that the ploughman in the field should have direct access to the songs and prayers of the faith. He had a feel, too, for the folly of the Gospel. One of his most famous and witty books is The Praise of Folly. He wrote: “Christ seems to take his greatest delight in little children, women and fishermen.”

In Erasmus sophistication was yoked to a yearning for simplicity, innocentia. Discipleship was not about a retreat from the world, about “being religious”, but about following the way of Jesus in the world. Key words for him were harmony, moderation, peacemaking. He said that mercenary warfare and the pursuit of martial glory were a dreadful curse. He condemned them in memorable terms: “Princes display brawn rather than intelligence.”

Today we could learn much from his passion for good communication. One of his intriguing insights is that conversation comes alive not through clever words on the lips of the speaker, or through the attentive ears of the listener, but in the space between. He had a profound awareness of the dynamics involved in a real meeting of minds. One mark of true humanity, he believed, was civility — patient listening to the viewpoint of those who differ from us — real dialogue. In the bitter controversies on everything from domestic to religious to political matters much could be achieved, he believed, if only those involved would agree to sit around a table in a respectful and prayerful manner.

Erasmus could wield an acidic pen. He had no patience with pomp and ceremony, a purely outward piety. He fiercely criticised Renaissance bishops and popes, such as Julius II, for their neglect of pastoral and theological matters and their participation in military campaigns. A savage satire, almost certainly written by him, portrayed Pope Julius being “excluded from heaven”. Erasmus and his followers campaigned for a better educated clergy and lampooned the pluralism, absenteeism and other abuses of the upper clergy. They also believed that proportions and priorities had been lost in much popular and superstitious piety. He said: “You could rush off to Rome or Compostela and buy up a million indulgences, but in the last analysis there is no better way of reconciling yourself with God than reconciling yourself with your neighbour.”

His concern for the unity of the Church distanced Erasmus from Luther — who described him, predictably, as a “slippery eel”. However, the truth is that their aims and perspectives were rather different. Erasmus stood for a gradual reform of the Church which would be achieved by a better educated clergy and by nudging the laity towards a personal, inward faith. For him the worst evil was hardness of heart and the best remedy — self-knowledge.

Erasmus also had his faults. He could be vain and twitchy when criticised. Some would say that he had scant appreciation of the sacramental and mystical life of the Church and tended to reduce the Gospel to a moral code. But like his great model, the 4th-century Church Father, Jerome, his long-term influence was benign and lasting. The humanist spirit he personified has nothing in common with modern humanism. His concern was profoundly religious and his championing of tolerance and moderation come close to what we would see today as a humane and liberal outlook.

We can glimpse his understanding and hope in his words: “Christian mercy should not be of the ordinary kind. God is appeased by several forms of sacrifice, spiritual hymns, songs, prayers, watchings, fastings, poor clothing; but no sacrifice is more effective than mercy towards your neighbour. Since we continually need God’s mercy in all things, we should always try to relieve each other with mutual mercy and to bear one another’s burdens. With one heart and one mind we shall sing eternally that the mercy of the Lord surpasses all his works.”

Tui Motu magazine Issue 214 April 2017:18-19