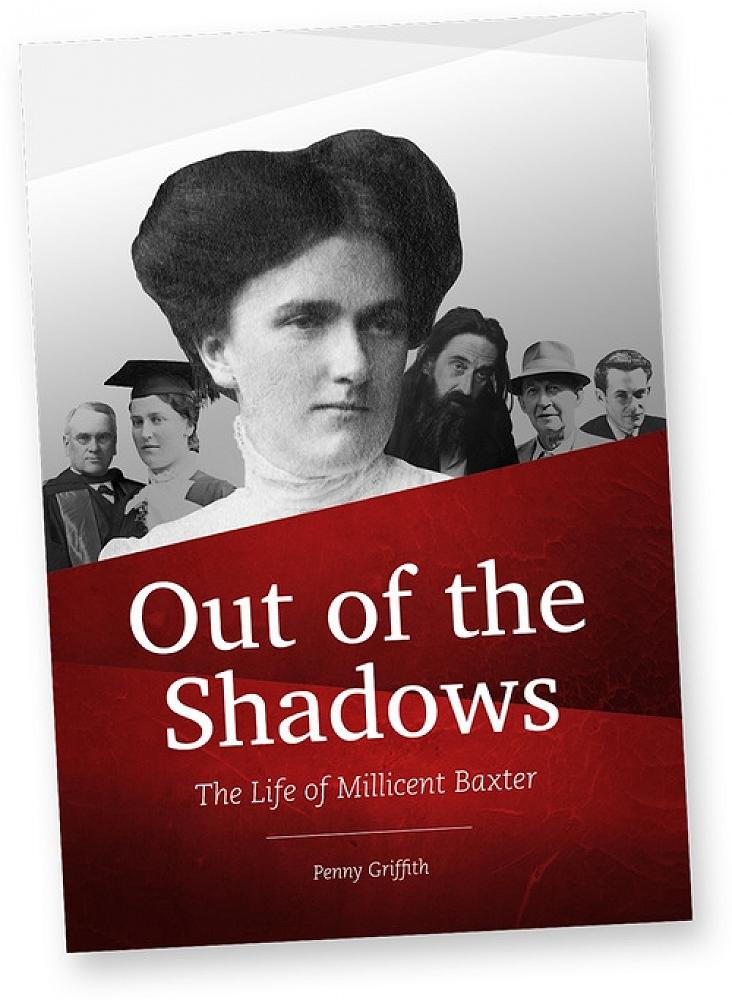

Out of the Shadows: the Life of Millicent Baxter

by Penny Griffith Published by PenPublishing: Wellington, 2015. Reviewed by Susan Smith

In her absorbing biography of Millicent Baxter, Penny Griffith argues that Millicent was often frustrated by other people’s descriptions of her as an “add-on”. As the daughter of Helen Connon, first woman graduate with honours in the British Empire and principal at Christchurch Girls’ High School, and of Professor John Macmillan Brown, a founding father of Canterbury University, the wife of New Zealand’s most famous pacifist, Archie Baxter, and the mother of New Zealand’s most famous poet, James K. Baxter, this was perhaps inevitable. Millicent did not want to be defined by her relationship with the significant people in her life. She was more than daughter, wife and mother. She was a well-educated, articulate and strong-minded woman, as Griffith demonstrates.

Does Griffith succeed in bringing Millicent out of the shadows of these noteworthy people? In Part 0ne, Child to Woman, the author outlines what it meant to grow up as one of the two daughters of Helen Connon and John Macmillan Brown, two noted intellectuals. Connon’s professional responsibilities and her death when Millicent was 15 meant a certain emotional distance between mother and daughter. And her father’s dominating, controlling personality and his hopes for her academic success meant the relationship between father and daughter was never easy. Although Millicent graduated BA in 1908 from the University of Sydney and continued her study of modern languages at Cambridge, UK and Halle University, Germany, she did not realise her father’s academic ambitions.

Further disappointments followed for Macmillan Brown. In 1914, Millicent returned to New Zealand and became a pacifist, something her father found very difficult to accept. But worse was to follow when in 1918 she married Archibald Baxter, the rabbiter from Otago, pacifist and New Zealand’s most famous conscientious objector during World War 1.

Part Two is primarily devoted to Archie’s story where the author covers the narrative of Archie’s imprisonment and the cruel punishments inflicted on him by the military authorities.

Part Three, by far the longest, covers Archie and Millicent’s married life, the birth of their two sons, Terence in 1922 and James in 1926. The couple’s pacifism often meant social isolation and alienation but hard work on the family farm and in 1935 a legacy from Millicent’s father ensured a certain financial security. The family travelled to England and Europe in 1936, returning to New Zealand in 1938. Part Three is concerned with Millicent’s story and also tells of her son Terence, who as a conscientious objector was imprisoned in a defaulter’s camp in 1941. Although he was treated far less harshly than his father had been, Millicent was convinced, with some justification, that the sins of the father were being visited upon the son.

A further chapter is devoted to The Poet Son and covers material that will be familiar to most readers — James K. Baxter’s extraordinary talent as poet, his marriage to and subsequent separation from Jacquie Sturm, his turbulent life-style and chequered career, his counter-cultural positions, his alcoholism, his conversion to Catholicism, the Jerusalem story and his death in 1972 in the house of strangers in Auckland.

The question for me in reading this biography was how successful was Griffith in bringing Millicent out of the shadow of the three extraordinary men in her life. If Griffith were to receive a grade for her ability to do this, I suspect I would have given her an A-. Given the place of religious faith in the lives of three of the protagonists in this biography, Millicent, Archie and James, this significant dimension could have been further researched and critiqued. Her father’s Anglicanism, Millicent’s embrace of Presbyterianism, Archie and Millicent’s later encounters with the Quaker community in England and in Whanganui and the conversion of Archie, James and Millicent to Catholicism, all merit further study. Perhaps, too, the emotional closeness and distances that seemed characteristic of the Macmillan Brown and Baxter families could have been examined more fully.

There is an impressive bibliography and that, coupled with generous footnotes, will ensure that this publication will be well utilised by those engaged in researching the role of women, of pacifism, of Archie or James Baxter. Out of the Shadows is an important contribution to those interested in the social history of New Zealand.

Published in Tui Motu InterIslands Magazine, Issue 205, June 2016.