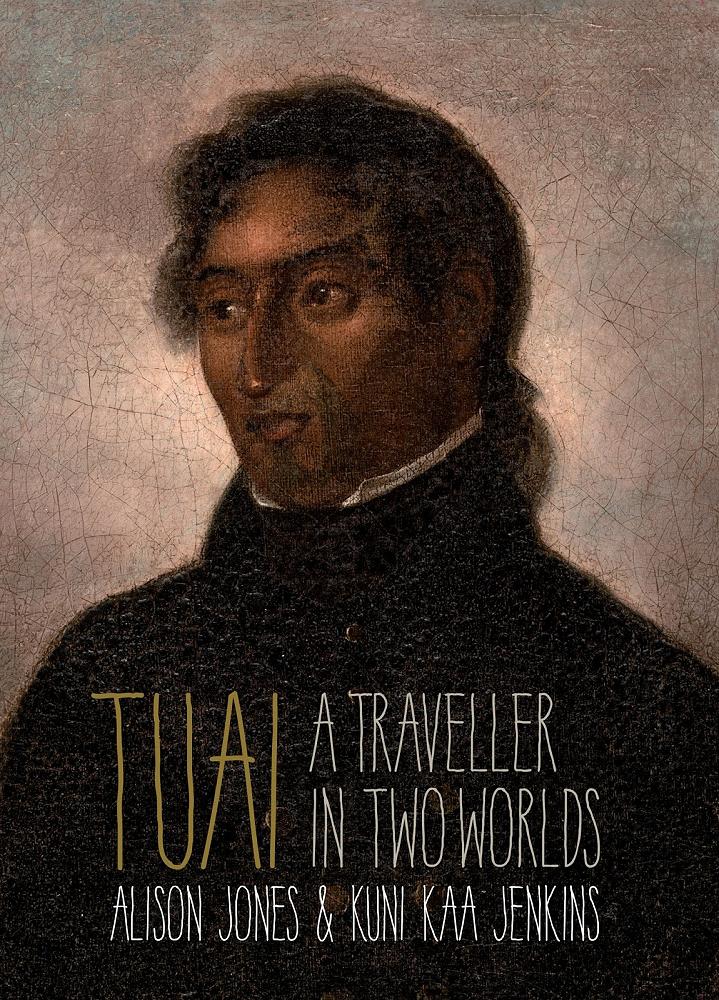

Tuai: A Traveller In Two Worlds

By Alison Jones and Kuni Kaa Jenkins. Published by Bridget Williams Books, 2017. Reviewed by Bernard Dennehy

Tuai was a young Māori rangatira of the Ngare Raumati hapū in the Bay of Islands. He is remarkable for his extensive travels to Australia and England from 1813, his role as go-between with missionaries and visiting ships and as translator and contributor to the first useful Māori grammar. He died at only 27 in 1824 after also assuming leadership of his hapū when older rangatira Korokoro and Kaipō passed on. He also helped defuse tensions with neighbouring hapū and took part in the musket wars in Hauraki, Tāmaki, Rotorua and Waikato.

From 1769, Māori showed intense interest in the European world, its technology, industry and agriculture — though not so much its Christianity. They travelled the world on whaling ships, foreign warships and passenger ships. The most well known were the chiefs Hongi Hika and Waikato who went to England in 1820, met King George IV and contributed to the Māori grammar produced by missionary Thomas Kendall and Professor Lee of Cambridge. The muskets they brought back triggered the calamitous “Musket Wars”.

Other less known early travellers, some voluntary and some kidnapped, are recorded as Ranginui, Tuku and Huru, Te Weherua and Koa, Te Pahi and Ruatara.

Reverend Samuel Marsden gave hospitality to large numbers of Māori visitors at his farm at Parramatta, New South Wales. Tuai was one of these visitors in 1813 and at Marsden’s request returned to New Zealand to prepare the way for the first group of missionary settlers in December 1814. Tuai did so and accompanied Mardsen, Korokoro, Kendall and others to Rangihoua.

In 1818 Marsden paid the passage to England for Tuai and his friend Tītere. There he was fascinated to witness the Industrial Revolution in full swing. He never converted to Christianity — in fact he turned against the missionaries for the derogatory way they spoke about Māori religion. For him the Māori had their “atua” and the Christians had their “god”.

Why is this book such a fascinating read? Somehow the authors have managed to capture and transmit to the reader the energy, enthusiasm and curiosity of Tuai. This remarkable young man, of chiefly status, achieved more than most in his brief adult life from 1813 to 1824. His interests were so varied that the reader does not tire of the record which passes from one experience to another.

This is an excellent biography recommended to all interested in pre-Treaty of Waitangi Māori-European encounters.

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 229 August 2018: 28-29