James K Baxter Complete Prose

Edited and Introduced by John Weir. Published by Victoria University Press. Reviewed by Cathy Harrison.

When you plunge into the depths of James K Baxter Complete Prose you could be forgiven for believing he is writing for New Zealand society today.

A labour of love and meticulous gathering of items, this project took John Weir about 50 years. Because of this time-span he would be surprised if any significant prose items have been omitted.

In compiling these four volumes Weir’s primary intention was to include all the prose which Baxter wrote in his lifetime — with the exception of his letters, which will be published separately.

His secondary intention was to date each item and place it in chronological order of composition. This device enables the reader both to see the range of topics which engaged Baxter at a particular time and to understand how his ideas persevered or developed — in fact, they were remarkably consistent from beginning to end.

In the Introduction Weir claims that less than ten per cent of the prose has been previously published in book form. The rest is either unpublished or was printed in journals or magazines which are ephemeral by their nature. So the novelty of much of the prose will surprise readers.

Initially the young Baxter viewed himself as a poet who would increasingly write prose when he was older. As the sequencing shows, the earliest prose items are usually about literary topics, while the later ones are chiefly about his religious and social concerns.

What’s most significant about it is that it is value-based. This is very apparent when Baxter contrasts the Trinity which he believed in (Father, Son and Holy Spirit) and the secular trinity which he described as the dollar, respectability and school certificate.

Baxter’s principles were offended by social injustices and he wrote compellingly about homelessness, poverty, unemployment, racism, militarism, capitalism and so on. The result is not just a literature of protest but a blueprint for change which advocates respect for the human person and empowerment for small communities.

In his article In my View [6] he claims: “the difference between Maori and pakeha is the difference between a community of neighbours and a society of strangers.” Baxter’s community and personalist values seem especially important whenever people’s rights are assaulted.

Through his personal and family experiences and his empathy for those on the margins he came to understand that the human condition is often wounded. But because he was a profoundly religious man he accepted the Christian belief that the Cross is really the Tree of Life and much of his late writing explores this paradox.

Like Thomas Merton, he based his social criticism on a framework of mystical and ascetical theology. This is especially apparent in his late prose which explores with enormous power the crucifixion of the oppressed.

The Complete Prose documents the life and times of a remarkable man with an unusual courage for self-disclosure and prolific social critique. In the final item, Confession to the Lord Christ, conscious that his “bones are taking him to the grave”, he reflects on what he would say to the great warrior who walked on the waters of Galilee and died on a cross. “E Ariki, taku ngakau ki a koe — Lord, my heart belongs to you.”

Baxter’s Complete Prose will be a fascinating source of material to readers especially those who are interested in spiritual and religious matters and social justice. Of course his enormous contribution to NZ and world literature must not be overlooked because he is regarded as one of the great poets in English of the 20th Century.

John Weir as editor and Victoria University Press as publisher together have produced a valuable resource for those who want to know more about New Zealand society, human vulnerability and the ideas which Baxter hoped would enable some people to move from dark to light.

“The guest should be welcomed with signs of love, and given food and drink — even if there is very little to eat in the house — and given a place to lie down.”

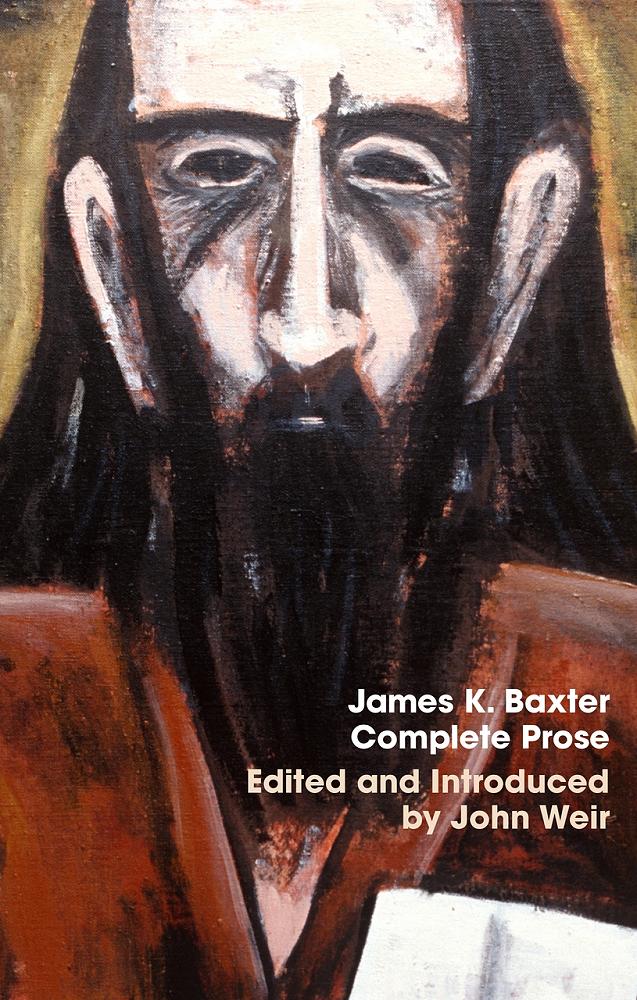

The central image from the title of

this article, The Six Faces of Love, is

mirrored in the design of the box which contains the four volumes because Nigel

Brown has symbolically depicted three faces of Baxter as prophet and

truth-teller. Like the prose, the illustrations are compelling.