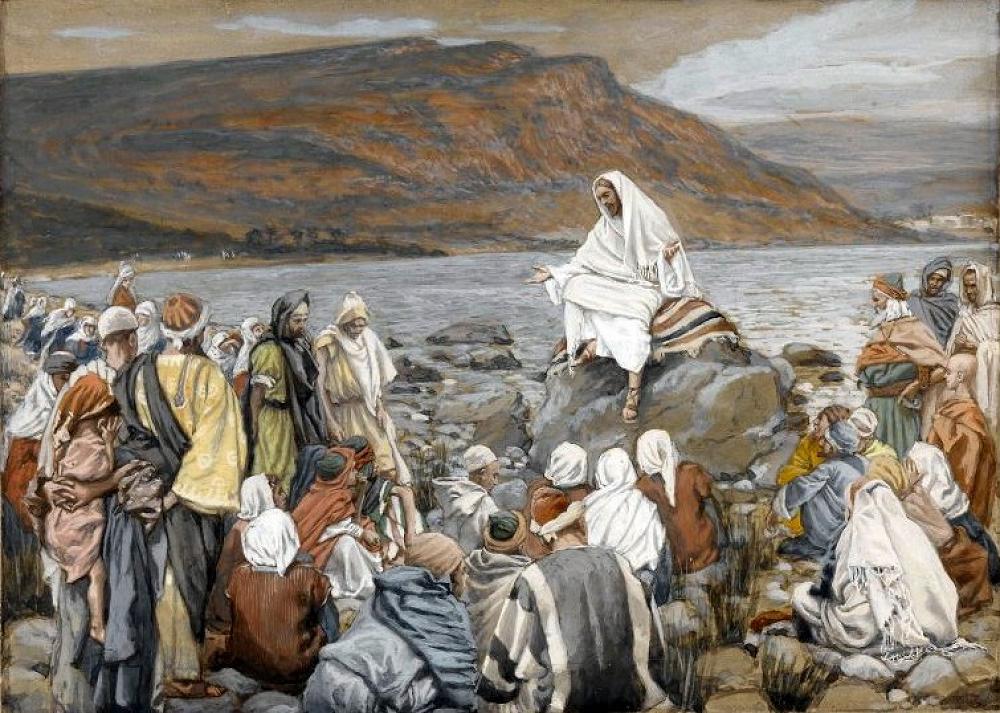

Blessed and Responsive — Luke 6:17-26

Kathleen Rushton highlights some significant aspects of Jesus's Sermon on the Plain in Luke 6:17-26.

Luke’s Gospel is preoccupied with the need to engage and dialogue with the world. It is highly likely that Luke’s focus on the plight of the poor was intended as a critique of his own congregation. Luke writes about Jesus in Palestine in the 30s for Christians living in the Greco-Roman world in the 80s. And now we are reading Luke’s words from the 2020s.

Understanding Limited Goods

Luke does not spiritualise poverty. In ancient Palestine the term “poor” was both a social and economic reality underpinned by the notion of “limited goods”. In our modern economies, we assume that goods are, in principle, in unlimited supply. If a shortage occurs, more can be made. But in ancient times, the opposite was assumed — all goods existed in finite, limited supply and were already distributed. This included everything in life — not only material goods but honour, friendship, power, status and security. We can imagine this understanding as being like a pie that is to be shared. If one person takes a large piece, then there is less for everyone else.

So when Luke calls someone “rich” he is making a social, moral and economic statement. And in labelling another “poor” means that the person is powerless and defenceless. It is closer to this understanding to translate “rich” as “greedy”, and “poor” as “socially unfortunate”.

Gospel Context of the Beatitudes

In Nazareth Jesus announced the programme for his ministry. Recalling Isaiah, he declared the Spirit of God is upon him, anointing him “to bring good news to the poor … to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind … to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of God’s favour” (Lk 4:16-19). Since then he has called others to engage in his ministry – Simon and his companions and Levi, the tax collector. In Chapter 5-6 Jesus moves to set up this group of companions on a more formal basis by founding his new community of the basileia of God. Then, in a long sermon, he lays out the attitudes and behaviours that are to distinguish his new community.

Before choosing the Twelve, Jesus spends the night in prayer on a mountain. The narrative implies that the Twelve were also there: “He came down with them and stood on a level place, with a great crowd of his disciples and a great multitude of people from all Judea, Jerusalem, and the coast of Tyre and Sidon.” (Lk 5:17). We need to distinguish the categories of people gathered on that level place where Jesus stands with them.

Those closest to Jesus are the twelve apostles, next are the wider group of disciples from whom the Twelve had been singled out, and then the great multitude. They had come to hear Jesus and to initiate their healing by “trying to touch him, for power came out from him”. It is vital to understand that Jesus gives his long instruction to his disciples in front of that huge gathering of burdened and afflicted humanity longing for his healing and freeing power. His deeds of healing (Lk 6:17-18) are followed by his words of teaching the Twelve for mission.

Meaning of “Blessed”

Jesus “looked up at his disciples”. He addresses them directly in the second person — using “you” and “yours”. The sermon contains the central truths he wants to communicate to potential disciples whom he calls “blessed” (Lk 6:21-23) and invites them to ongoing conversion (Lk 6:24-26). In the four pairs of blessings and contrasting woes, the emphasis is on now.

Two words in Luke are translated as “blessed.” One (eulogeō) is found when a person asks a blessing for an individual or persons as when Simeon “blessed” Mary and Joseph or Elizabeth “blessed” Mary.

The other (makarios) in the beatitudes and in Mary’s Magnificat, is described by Raymond Brown as “not part of a wish [or] blessing but rather recognising “an existing state of happiness or good fortune.” In this sense, “blessed” affirms a quality of spirituality that is already present. It is about a happy state that already exists and allows one even now to experience a happy life. In the New Testament, this blessed is overwhelmingly about the distinctive joy that a person experiences in being part of the basileia of God.

The Beatitudes

The Beatitudes are provocative and they hold together clashing ideas. They do not suggest that the poor are to be content and accept their lot passively. Jesus speaks of God acting on behalf of the poor and marginalised rather than the greedy and comfortable. Disciples who throw in their lot with Jesus are called to conversion. The paradox is that at the same time as Luke proclaims “woe to you who are rich” those same rich, entering into the new community of the basileia, will be “blessed . . . yours is the kingdom of God . . . you will be filled.”

The “poor” denote the economically poor. These Beatitudes, like Mary’s Magnificat, cannot be spiritualised as if they have no relationship to social justice. But “the poor” also describes the faithful of Israel like Anna and Simeon — and the multitude seeking Jesus — who are waiting with hope for God’s coming among them. They show that at the heart of longing for economic, structural and environmental salvation, is a deep spiritual longing.

Letting the Beatitudes Influence Us

What Jesus says and does in the Sermon on the Plain is directly relevant to our Christian communities today. The Lucan Jesus invites us to participate with him in God’s basileia in several interconnected ways.

First Jesus takes time for prayer — disciples are there. Prayer and action go together.

Second, Jesus stands with and he does not minister alone — he calls us together as a community, a moral community that can support and challenge our search for truth and ways forward.

Third, Jesus gives his instruction on the distinguishing attitudes and behaviours of discipleship with the afflicted crowd before him.

Fourth, Jesus speaks directly to us: “You are blessed”, affirming a quality of spirituality that is already present, an experience of joy in our longed-for change. We are invited to ongoing conversion and transformation.

And fifth, like Jesus we can draw on the deep tradition of the practical wisdom.

This is what the Churches are for — to nourish an experience of transcendence, a shared praxis and alternative vision to sustain us in an often-hostile environment and to communicate this living tradition to others. With Luke’s community, we face this challenge in our particular situation today — to conserve, live and transmit both their and our experience of Jesus and God’s alternative community of the basileia.

Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 267 February 2022: 24-25