Welcoming the Stranger

Mary Betz remembers her great-grandmother opening her home to travelling workers during the Great Depression and reflects on the encounter at the heart of hospitality.

My great-grandmother, Laura, lived for 102 years in southern Illinois, across the Mississippi River from St Louis. I remember the candy jar, cups of lemon tea and extended family dinners at her home. Among many stories about her, one has stayed with me particularly. During the Great Depression there was a constant string of “hobos” knocking on Laura’s door and she never sent them away with empty hands. She often invited them in for a hot meal and a wash.

I marvel at Laura’s hospitality to homeless, jobless, often dirty and lice-ridden men whom she had never set eyes on before. It is one thing to offer hospitality to friends, family and acquaintances — offering it to strangers is quite another.

Traditions of Hospitality

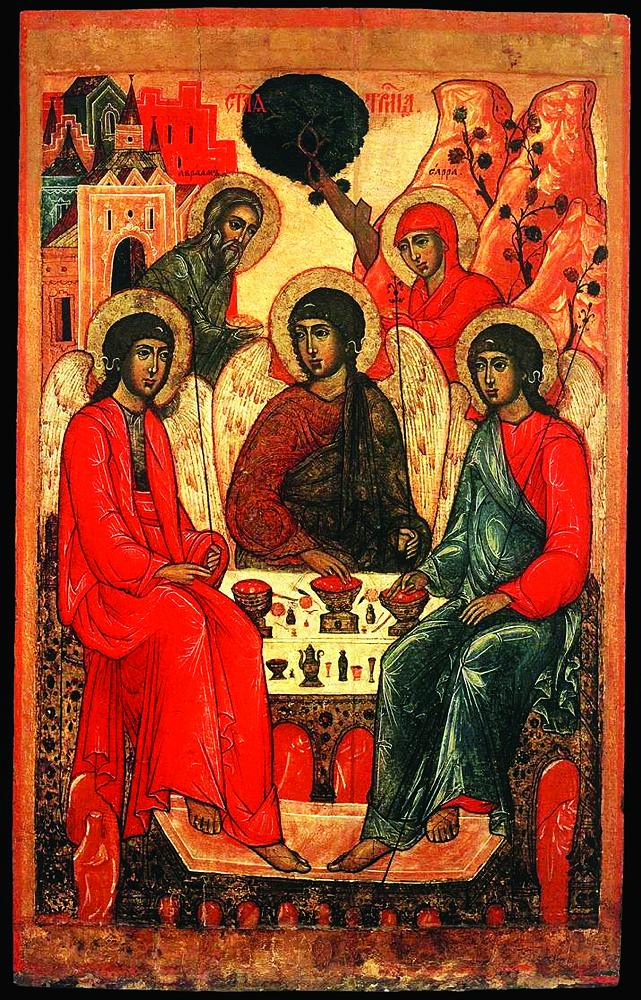

And yet, the word “hospitality” has as its Latin root hospes/hospita — one who entertains or lodges a stranger, and interestingly — the one who is entertained or lodged — the guests, strangers or foreigners themselves. Long before the Romans, the tradition of hospitality was engrained in ancient Middle Eastern cultures. The Hebrew Scriptures are full of enjoinders to “share your bread with the hungry and bring the homeless poor into your house” (Is 58:7). On many occasions the host was rewarded, as when Abraham and Sarah were blessed with a child in return for hospitality to heavenly sojourners (Gen 18:1–15).

The Gospels recount the hospitality shown to Jesus, as at the homes of Martha and Mary (Lk 10:38ff) and Zacchaeus (Lk 19:1–10) — where Jesus invited himself. They also depict hospitality not shown, as by Simon the Pharisee (Lk 7:44ff). Jesus too was portrayed as welcoming and caring. He invited two of John the Baptist’s followers to “come and see” him at home (Jn 1:39). He was concerned to feed those who followed him through the countryside (Mt 14:13ff), barbequed fish on the shores of the Sea of Galilee (Jn 21:9) and of course hosted the Last Supper.

The Emmaus story (Lk 24:13ff) is a striking illustration of hospitality and its sometimes surprising consequences. After the death of Jesus, two disciples were returning home devastated, but hospitably allowed a “stranger” into their conversation on the road. The stranger was an attentive listener and a good teacher and tired as they were, the disciples found themselves entranced by him, urging him to stay on with them in Emmaus. The stranger agreed, then shifted the roles returning hospitality by breaking bread for them. Through this mutual hospitality the disciples were enabled to see in the stranger — the face of Christ.

Learning to Give and Receive

It is as if the reflexive meaning of the Latin word often carries on in the way hospitality is lived out. Everyone I know who has worked with refugees over extended periods of time has found that as they extend hospitality to others, it leads to engagement, listening and understanding, recognition of Christ in the other, and often in mutual learning and friendship.

But hospitality is not just a pleasant smile or even an offer of a meal. It is a deliberate offer to listen and attend to the needs of a stranger or friend — and a step into the unknown. Sometimes I have invited travellers or needy strangers into my home — with varying outcomes. Usually there have been short periods of accommodation and meals. Sometimes long-term friendships have been forged.

But more than once I discovered I lacked “street-smarts” and knowledge of available social and mental health services. And the stranger’s needs began to turn my life upside down. Maybe that was the point because soon I began asking questions about why the poor and mentally ill had no place to go. Hospitality to strangers is often intertwined with questions that lead us to issues of justice and mercy.

Early Christian Hospitality

From Christianity’s earliest years followers of Jesus were urged to welcome strangers and those in need on an individual and local community basis. St John Chrysostom saw failures in this regard and spared no sarcasm in his lament:

“Christ has nowhere to lodge, but goes about as a stranger, and naked and hungry, and you set up houses out of town, and baths and terraces and chambers without number . . . and to Christ you give not even a share of a little hut.” Ouch.

In later centuries following Constantine’s legalisation of Christianity, multi-purpose “hospitals” were established to care for the poor, sick, homeless, travellers and pilgrims — and many of these continued to operate right through the Middle Ages. They were attached to monasteries or were diocesan entities.

By the 18th century institutions offered “hospitality” to people with various needs in separate, increasingly secular institutions. Individuals like Vincent de Paul and later, Dorothy Day and Jean Vanier met needs for a home and hospitality in their own times and places. Their work carries on today in the Vinnies, the Catholic Worker movement and L’Arche communities.

Need for Hospitality Now

Today many New Zealanders struggle with poverty, inequality and a housing crisis which John Chrysostom would find tragically familiar.

Thousands of families and individuals are sleeping in cars, garages and shacks, or under bridges — the New Zealand Council of Christian Social Services recently put the number at 42,000. Emergency housing providers like Auckland’s De Paul House and Monte Cecilia have long waiting lists.

In the spirit of manaakitanga, Te Puea Marae opened its doors to homeless families in May this year and was quickly filled. In the 19th century, the tangata whenua welcomed migrant Pākehā and shared their land with them. Tragically, Māori are now some of those most in need of similar hospitality. And from overseas the call for justice through hospitality to homeless refugees continues to grow.

Becoming Hospitable People

In 2015 Pope Francis addressed the World Meeting of Popular Movements, reminding them that

“the future of humanity does not lie solely in the hands of great leaders, the great powers and the elites. It is fundamentally in the hands of peoples and in their ability to organise . . . Each of us, let us repeat from the heart: no family without lodging . . . no individual without dignity.”

Hospitality is a responsibility of our nation and its people. Individuals and communities often choose to offer hospitality because it is part of their faith tradition or value system, or because their hearts tug at them to do so. Unfortunately it is often only when a groundswell of citizens demands action, that governments respond with justice towards their own homeless and consider the plight of refugees. We need to practise the welcome, justice and mercy of hospitality. In engaging with the “stranger” we can be changed forever by the encounter.

I have lived with Great-grandma Laura’s goodness in my heart but it always puzzled me why there would have been so many hobos around her home. This week I looked at an old map and discovered railway tracks and holding yards in all directions only blocks from her house. The men usually rode the rails in search of work so Laura was in the right place for them. While we may not have hobos knocking on our doors, if we open our eyes and hearts to recognise who is knocking now, we will be in the right place for them too.

Published in Tui Motu InterIslands magazine. Issue 206, July 2016.